By Hassan Ahmed

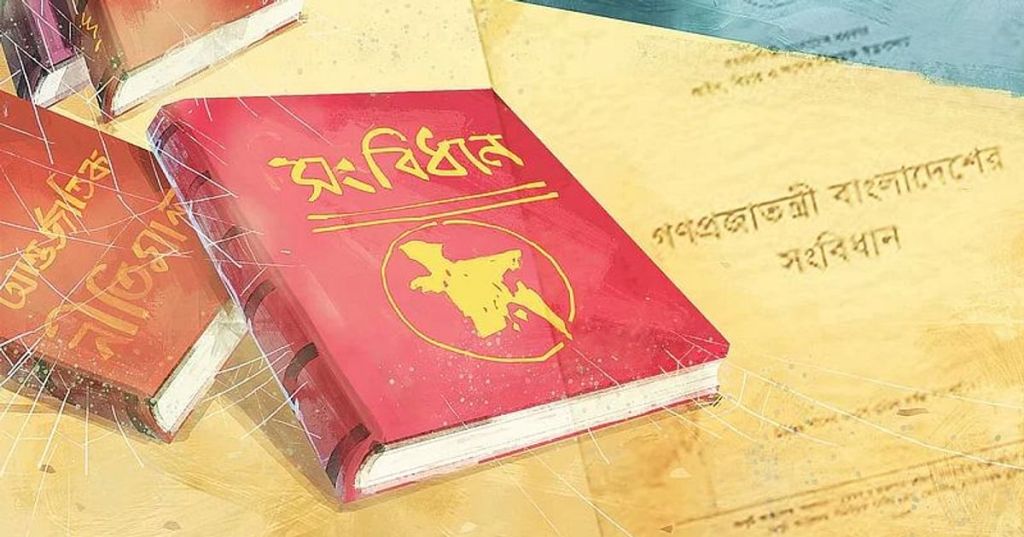

Bangladesh stands at a pivotal moment in history. The ousting of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and the rise of an interim government led by Nobel laureate Dr. Muhammad Yunus marks the latest chapter in this young republic’s story, one defined by political intrigues and constitutional manipulation. This is not the first time the nation has faced such an upheaval. Since its inception and subsequent independence, Bangladesh’s political landscape has been shaped, reshaped, and often destabilized by a series of constitutional amendments, each reflecting the ambitions and fears of those in power. In particular, the conflict between a vaguely defined Islam and an equally nebulous conception of secularism has been a key and persistent issue. This tension, which has played out emotionally at the constitutional level, has been both a reflection of, and a catalyst for, the country’s broader political struggles. As Bangladesh navigates yet another period of political uncertainty under the interim leadership of Dr. Yunus, this underlying conflict remains as relevant as ever, shaping not only the nation’s identity but also its future trajectory.

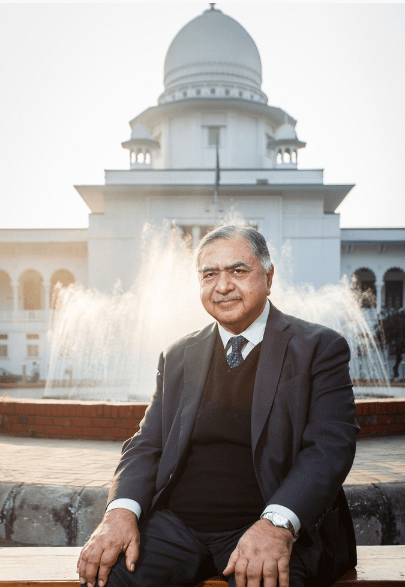

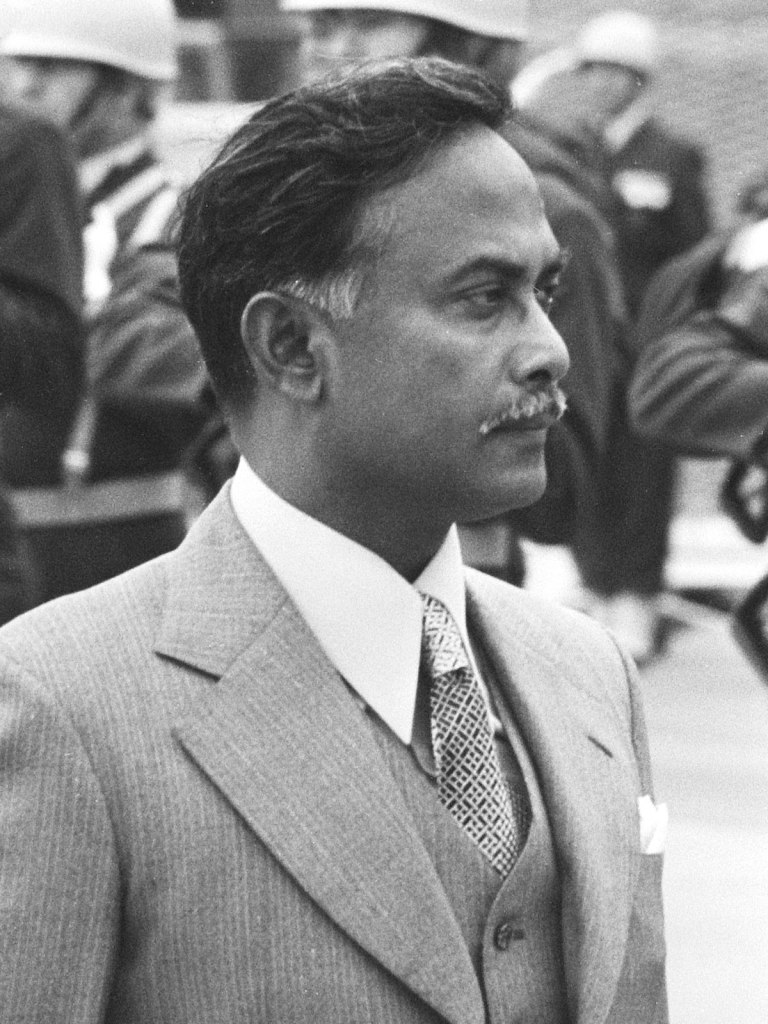

In 1972, when the Constituent Assembly of Bangladesh and the newly-formed government of “Bangabandhu” Sheikh Mujibur Rahman introduced a constitution that enshrined the principles of nationalism, socialism, democracy, and secularism. Constitutional architect and senior jurist, Kamal Hossain (কামাল হোসেন), intended for these four pillars to guide the republic toward a stable and just society, free from autocratic rule and exploitation that had characterized the decades spent as Pakistan’s “fareast colony”. Secularism, in this context, was not merely the absence of religion from the state but an active policy to protect religious minorities and prevent the dominance of any single religion—specifically Islam, which had been used as a repressive political instrument by the previous junta-dominated Pakistani state. Constitutionalism, as envisioned by the likes of the first, albeit provisional, Prime Minister Tajuddin Ahmad (তাজউদ্দীন আহমদ), was quickly eclipsed by Mujibbad (মুজিববাদ) — the eponymous personality cult imposed soon after independence.

However, the idealism of the early 1970s soon collided with the harsh realities of governance in a war-torn nation born smack in the middle of the first Cold War. Economic difficulties, political unrest, and rising discontent culminated in the Fourth Amendment of 1975, which radically transformed the political framework of Bangladesh. The amendment, driven by Sheikh Mujib himself, established a one-party state under the banner of the BAKSAL (Bangladesh Krishak Sramik Awami League), expanded presidential powers, and significantly curtailed the independence of the judiciary and the press. Although the amendment did not directly address religion, the increasing centralization of power and the marginalization of dissent allowed for the gradual erosion of secularism as a guiding principle.

The need to restore order and stability in a country struggling to recover from the ravages of war emerged as the primary justification for these changes. However, the Fourth Amendment also marked the beginning of a trend toward authoritarianism, concentrating power in the hands of a paramount leader and marginalizing dissenting voices. This centralization of power would set a dangerous precedent for future leaders to emulate and enhance. In turn, successors have wielded constitutional amendments as their preferred legal tool for maintaining control through arguably dubious means.

The history of Bangladesh’s constitutional amendments reveals a pattern of opportunism rather than constitutionalism. Each ruling interest has sought to use the constitution as a weapon to entrench itself in Dhaka. Rather than upholding the constitution as the supreme law of the land, a framework for democratic governance that protects citizens and state alike, successive ruling interests have taken it upon themselves to subordinate and subvert constitutionalism. The Fourth Amendment in 1975, the Fifth Amendment in 1979, the Eighth Amendment in 1988, and the Fifteenth Amendment in 2011 all reflect how the Constitution has been manipulated to serve the interests of those in power, with Islam and secularism being the calling cards of both democrats and dictators, whatever that means anymore. Due to the winner-take-all nature of Bangladeshi electoral politics, the constitutional amendment formula outlined under Article 142 in Part X allows for a fast-tracked path towards broad and sweeping changes to the very character of the republic.

The flexibility of Article 142, particularly under a first-past-the-post electoral system, has played a critical role in these developments. Article 142 allows amendments with a simple two-thirds majority in the unicameral Jatiya Sangsad (জাতীয় সংসদ), enabling ruling parties to push through significant changes with minimal effective opposition. In contrast, more stable democracies often require broader consensus, either through a constitutional convention or through approval from multiple legislative bodies and branches of government before such changes can be enacted. This level of constitutional malleability has allowed successive governments to mold the Constitution to fit narrow political agendas, often at the expense of democratic credibility and political integrity.

Mujib’s assassination on 15 August 1975 plunged Bangladesh into a period of intense political instability, marked by coups, counter-coups, and a series of military régimes. Bangladesh became an “état de coups d’état”. Each régime sought to legitimize its rule through top-down constitutional changes. Lieutenant General Ziaur Rahman (জিয়াউর রহমান), who emerged as a key figure during this period, made significant amendments to the constitution after taking power in a military coup in 1977. One of his most notable changes was the Fifth Amendment in 1979, which retroactively validated all actions taken by the military government following the 1975 coup, reinstated multi-party freedom of assembly, albeit with significant limitations, and replaced the term “secularism” with “absolute trust and faith in the Almighty Allah,” (Part II, s.8(1)). The latter effectively marked a sharp departure from the civic secularism of the original constitution. This move was both a political strategy to gain support from politico-religious factions and a reflection of the changing societal landscape in Bangladesh. The Fifth Amendment, while disestablishing one-party socialism, also embedded the military’s role in politics. This set the stage for further manipulations of the constitution.

Recognizing the problem with a Constitution that is too malleable, the Fifth Amendment also attempted to mitigate the ease with which the Constitution could be amended, requiring a referendum in addition to the two-thirds majority in parliament for amendments to the Preamble or other articles consolidating the presidential system vis-a-vis the Prime Minister and cabinet and the parliament. In 2010, the Fifth Amendment was invalidated by the Supreme Court of Bangladesh however, who wryly noted that the Fifth Amendment itself was introduced by the Executive Order of one person, namely the Chief Martial Law Administrator and President, but limited the ability of Parliament, a democratically elected body, to amend the constitution, something the Supreme Court dismissed, stating that “we are simply charmed by the sheer hierocracy of the whole process”.

General-cum-President Ziaur Rahman’s assassination and the rise of Lieutenant General H.M. Ershad (এরশাদ) further entrenched this trend of constitutional manipulation. Ershad also used constitutional amendments to grow his powers and extend his rule. Constitutionalism regressed dramatically under military rule, crippling both civil society and future civilian governments alike. Gen. Ershad’s régime, like those preceding it, relied on straightforward constitutional manipulation in order to legitimize authoritarian rule while suppressing opposition nationwide.

The Eighth Amendment of 1988, which declared Islam as the state religion, was the most explicit constitutional move away from secularism. This amendment reflected the growing influence of Islamic revivalism that was occurring worldwide in that decade, and Bangladeshi socio-political discourse was not immune from it. However, this shift in legal paradigms resulted in increasingly divisive attitudes within the country more broadly. While Gen. Ershad sought to legitimize and reinforce his rule by appealing to ethno-religious identity politics, the amendment simultaneously alienated minorities and secularists, setting the stage for ongoing conflicts over the role of religion in statecraft and governance.

The fall of Ershad in 1990, amid widespread protests and a popular uprising, led to the restoration of parliamentary democracy with the Twelfth Amendment in 1991. This amendment is often seen as a corrective measure, rolling back the powers of the presidency and restoring the Westminster-inflected parliamentary system envisioned in the original constitution. The amendment served to reign in the military, presidential authoritarianism, rule by decree, and state-sponsored dominant-party politics.

The Thirteenth Amendment of 1996 introduced the caretaker government system, a novel and theoretically apolitical mechanism designed to oversee free and fair elections by placing executive authority in the hands of a neutral, non-partisan temporary cabinet for a constitutionally restricted time period. The caretaker administration’s sole responsibility was to hold impartial elections within 90 days of taking office and transfer power to the newly elected government within 120 days.

For a time, it seemed that Bangladesh was on the path to democratic stability. However, the caretaker government system, while initially effective, became a point of intense political contention. During her second term as prime minister, Sheikh Hasina’s government pushed through the Fifteenth Amendment in 2011, abolishing the caretaker government system. This made Fakhruddin Ahmed, former governor of the central bank, the last constitutionally recognized Chief Adviser and caretaker head of government in 2009. Critics saw this as a strategic checkmate to ensure that the ruling Awami League could influence the electoral process indefinitely. Abolishing the caretaker system effectively undermined the democratic guardrails that had been developed and established two decades prior. The amendment was met with widespread criticism, deepening the political rift between supporters of the Awami League and their arch-rivals within the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), the country’s two dominant political forces.

The Fifteenth Amendment did more than just abolish the caretaker system. It also reaffirmed secularism as a fundamental principle of the state, while simultaneously retaining Islam as the state religion—a seemingly contradictory stance that highlighted the complex and often schizophrenic bipolarity of Bangladeshi political identities. This duality in the constitution—where secularism and Islam coexist in a precarious balance—reflects broader societal tensions in Bangladesh and many other contemporary Muslim-majority Kokutai worldwide. The retention of Islam as the state religion, even as secularism was reaffirmed once more, highlights the political necessity for leaders to navigate between the demands of a secular, pluralistic state and the religious sentiments of an overwhelmingly large portion of the population. This balancing act has often led to compromises that satisfy neither side fully, leaving the door open for further conflicts and attempts by one to out manœuvre the other. The amendment also included immunity provisions to prevent future amendments from altering the basic structure of the constitution, a move aimed at protecting the supposed secular and democratic character of the state. Given that the political landscape in Bangladesh has become increasingly polarized since the Fifteenth Amendment, with elections in 2014 and 2018 being marred by allegations of vote-rigging, violence, human rights violations, and opposition boycotts, these protections have been viewed with skepticism by critics who argue that they were more about safeguarding the interests of the ruling party than ensuring democratic continuity. The Awami League’s use of state resources and institutions to maintain its hold on power drew criticism both domestically and from abroad, culminating in the forced removal of the Hasina government and leaving the future of the Fifteenth Amendment and its restrictions on future amendments subject to further uncertainty.

With Dr. Yunus now at the helm of an extra-constitutional interim government, the debate over the length and scope of his leadership has become a jurisprudential focal point for national discourse and discord. Some advocate for a brief transitional period leading to fresh elections, akin to the previous caretaker governments, while others argue that a longer tenure is necessary to implement meaningful reforms for good governance, particularly in addressing the constitutional vulnerabilities that have allowed for such frequent and sweeping changes. The ongoing debate surrounding the duration of Dr. Yunus’ interim government is emblematic of the tension between immediate political stability and long-term democratic values. If the interim government can introduce reforms that make it more difficult to amend the constitution—perhaps by requiring broader legislative approval or establishing a constitutional convention—it could set a precedent for a more resilient era for democracy in East Bengal. At the same time, given the unelected nature of Dr. Yunus’ government, it is entirely possible that any decisions and directives taken by this interim administration, particularly as they relate to constitutional amendments, will be declared null and void by the judiciary at a future point in time, similar to what happened with the Fifth Amendment. This risk is further amplified by the fact that Dr. Yunus is not a civil servant, a jurist, or a judge, nor is he a serving or retired officer of the armed forces. Without such markers of legitimacy nor a democratic mandate, Dr. Yunus risks becoming a Bangladeshi Louis XIV or an equivalent Raja or Nawab, without notions of “Divine Rights” behind him.

In contrast to the American constitutional paradigm, which displays an inertial resistance to changes in grand mythopia, Bangladesh’s constitutional history demonstrates a tectonic tendency, akin to the style of constitutionalism found in Western Europe (sans the UK). That said, in Bangladesh these major changes have always taken the form of amendments to the original 1972 Constitution, as opposed to a wholesale re-write like the one that took place in post revolutionary Iran in 1979. Nonetheless, though small, an increasing number of voices within Bangladesh are beginning to discuss the possibility (some would say need) of taking on this more radical approach, which would transform Dr. Yunus from the seemingly quiet technocrat to a much more revolutionary figure. While such a prospect is intriguing, the chances of the regime going down this path seem low; so far, the government has tried to maintain at least the appearance of a transitional technocratic regime, perhaps due to their keen awareness that they do not have the widespread democratic mandate nor the revolutionary fervor needed for such a radical overhaul. The overthrow of Hasina was not the flight of the Shah, and Dr. Yunus is no Khomeini. Accordingly, the government has thus far limited itself to setting up a Constitutional Reform Commission, while, in standard bureaucratic fashion, remaining vague about the scope of its mandate.

If, despite the challenges and risks associated, the interim government under Dr. Yunus does decide to seriously proceed with constitutional reforms, it will have to navigate a minefield of political and social sensitivities over the role of Islam in the state without having a democratic mandate to do so. Any attempt to amend the constitution to either strengthen secularism or further institutionalize Islam will likely provoke strong reactions from various quarters. As Islamists and secularists vie for influence, the constitution remains a battleground for competing visions of the nation’s identity.

The tension between Islam and secularism is not just a constitutional issue; it is a reflection of the broader struggle over what it means to be Bangladeshi and how citizens view their People’s Republic (গণপ্রজাতন্ত্রী). As the nation moves forward, this unresolved conflict will continue to shape its politics, its society, and its future. Whether Bangladesh can find a way to reconcile these competing forces—or whether it will remain trapped in a cycle of constitutional manhandling and political insurgency—remains to be seen. But it is clear that the nation’s identity, forged in the crucible of a bloody struggle for independence, is still very much in flux, with the constitution as both a tool and a battleground in this ongoing struggle.

Dr. Yunus has a rare opportunity to address these deep-seated issues, but it will require more than just political will. It will require, first and foremost, for him to legitimize his own rule, either via the existing structures of power or through the creation of new ones, and then a commitment to rebuilding Bangladesh’s democratic institutions, restoring public trust in the electoral process, and having a difficult national conversation about secularism and Islam. The decisions made in the coming months will determine whether Bangladesh can break free from the cycle of political manipulation and authoritarianism or whether it will continue to struggle with the same issues that have haunted it for decades. The constitutional history of Bangladesh is a cautionary tale, and the lessons of the past must be taken seriously if the country is to chart a new course toward a more stable and democratic future.

What a very insightful article!

LikeLike