The Editorial Board

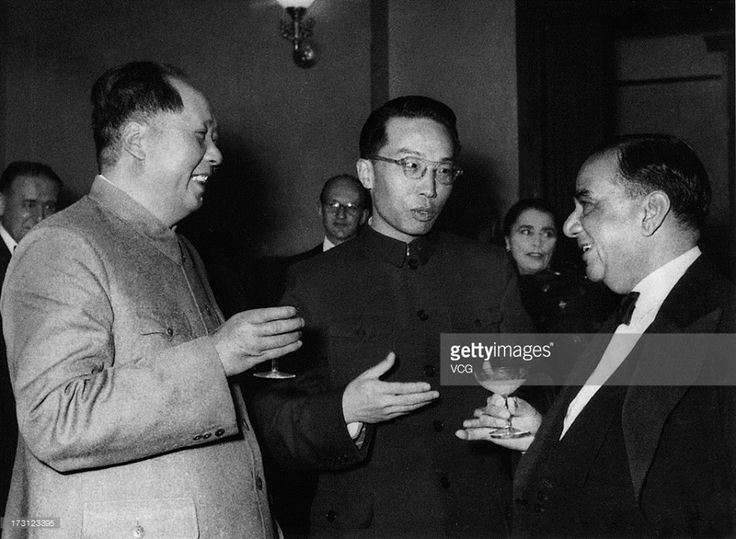

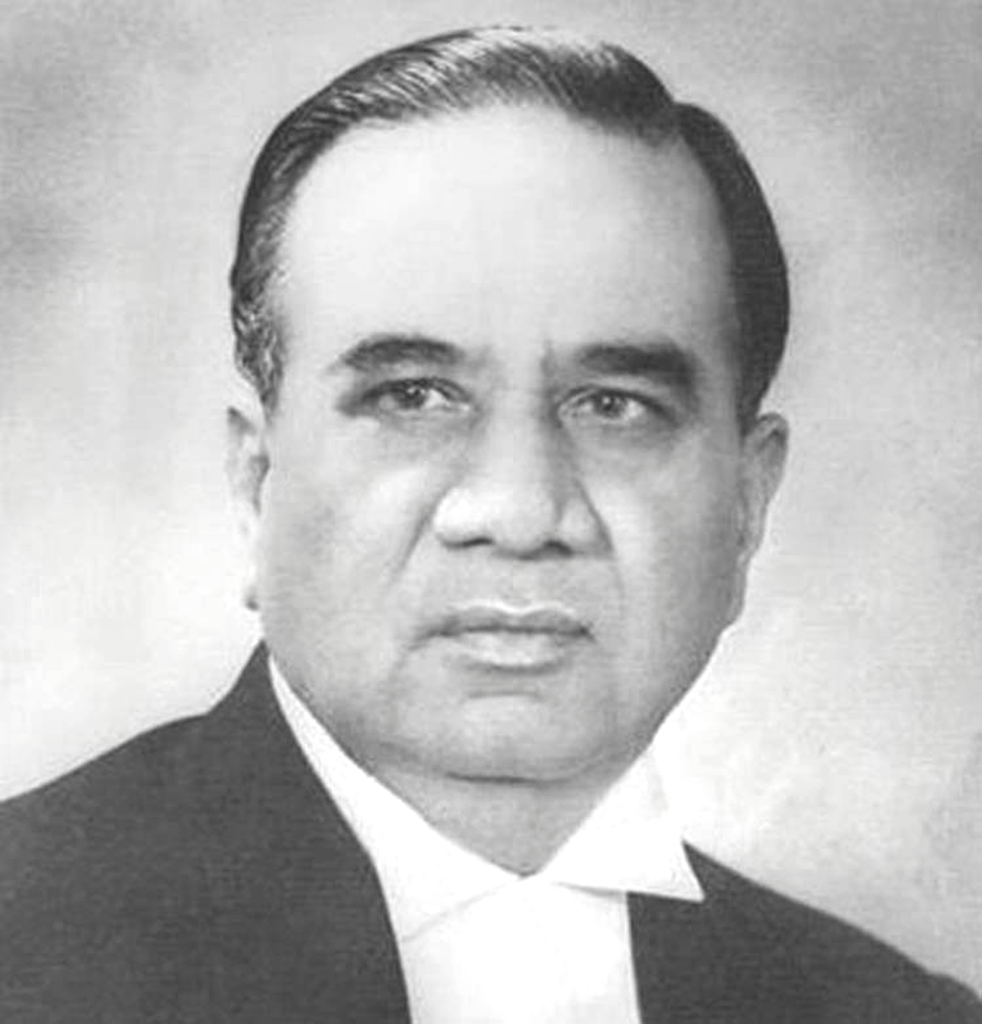

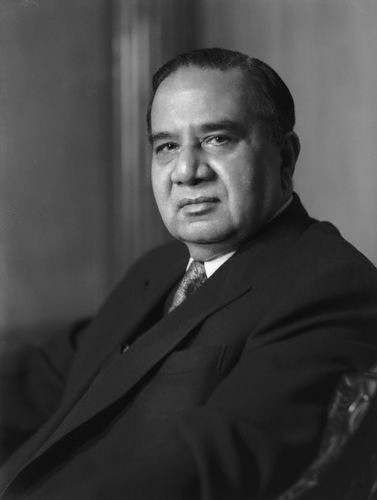

One fine summer night in July 1956 in Los Angeles, a presidential motorcade cruised down Sunset Boulevard from the legendary Pickfair mansion in Beverly Hills to the historic Ambassador Hotel in the L.A. neighborhood known today as Little Bangladesh.

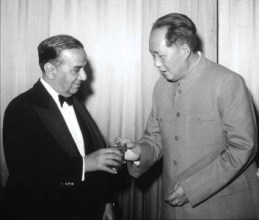

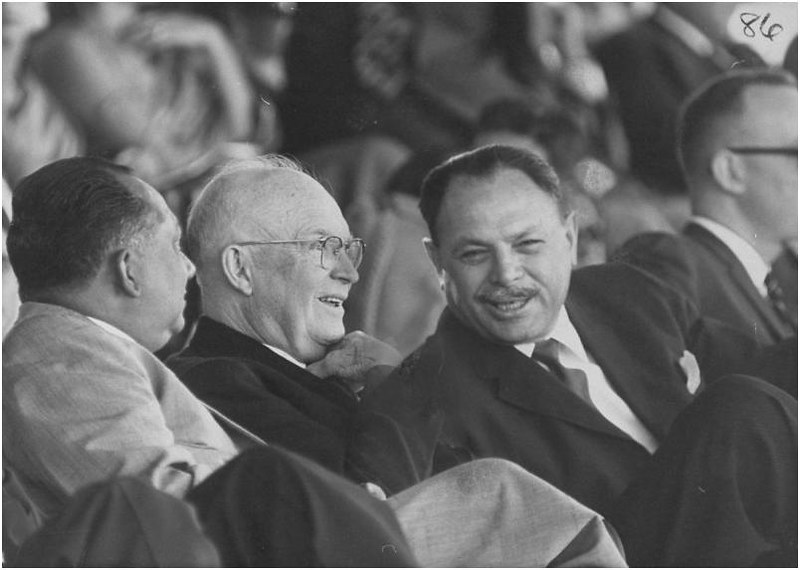

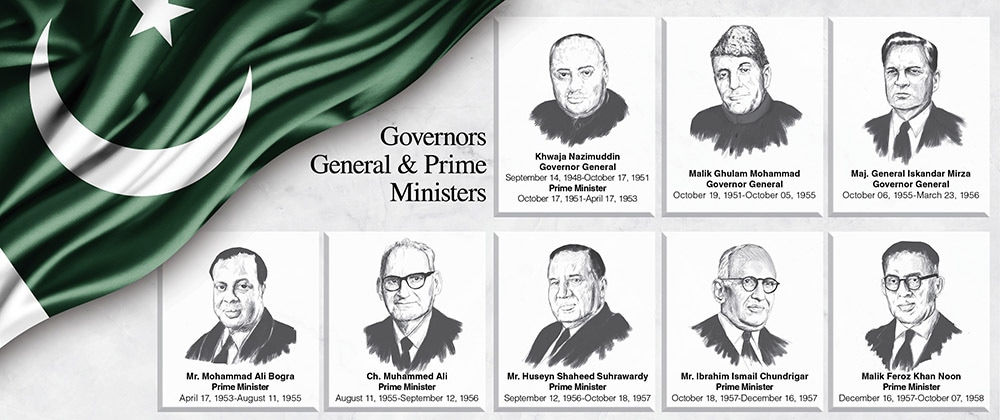

The motorcade was escorting the fifth Prime Minister of Pakistan, a Bengali politician and lawyer named Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, who had just met with U.S. President Eisenhower in D.C., was set to tour Las Vegas, the Hoover Dam and the Grand Canyon next and was now meeting movie stars in Hollywood. After partying late into the night, the Bengali Prime Minister of Pakistan was found in the hotel lobby at 3 A.M., enjoying sandwiches and orange juice with the U.S. State Department’s Chief of Protocol, Wiley T. Buchanan. The next morning, he would be seen totally rested in his silk white pajamas, back to discussing a range of political issues facing Pakistan as head of state with the press including the nuclear program, joint electorates and joining Cold-War era military pacts.

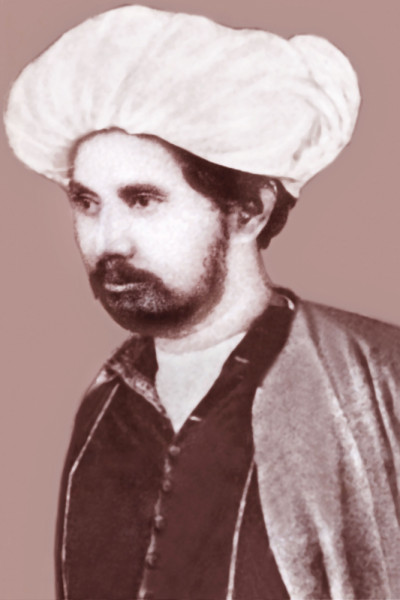

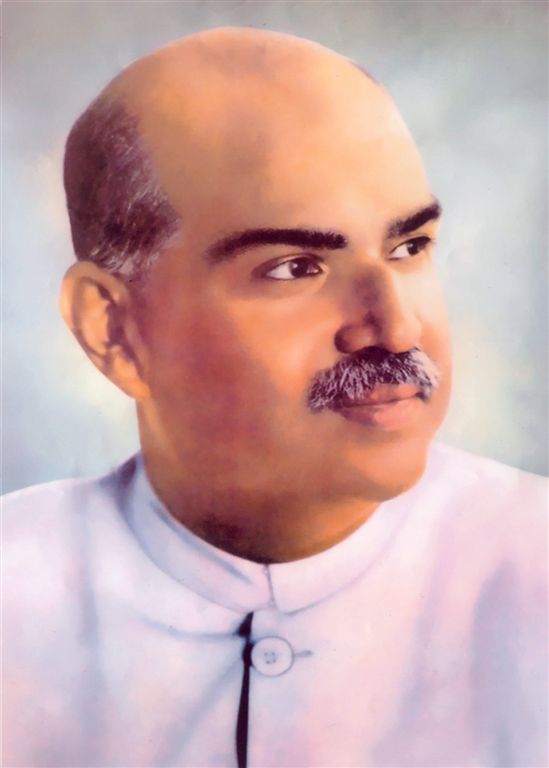

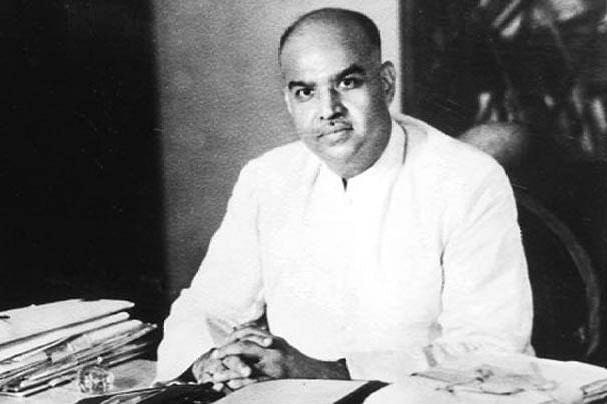

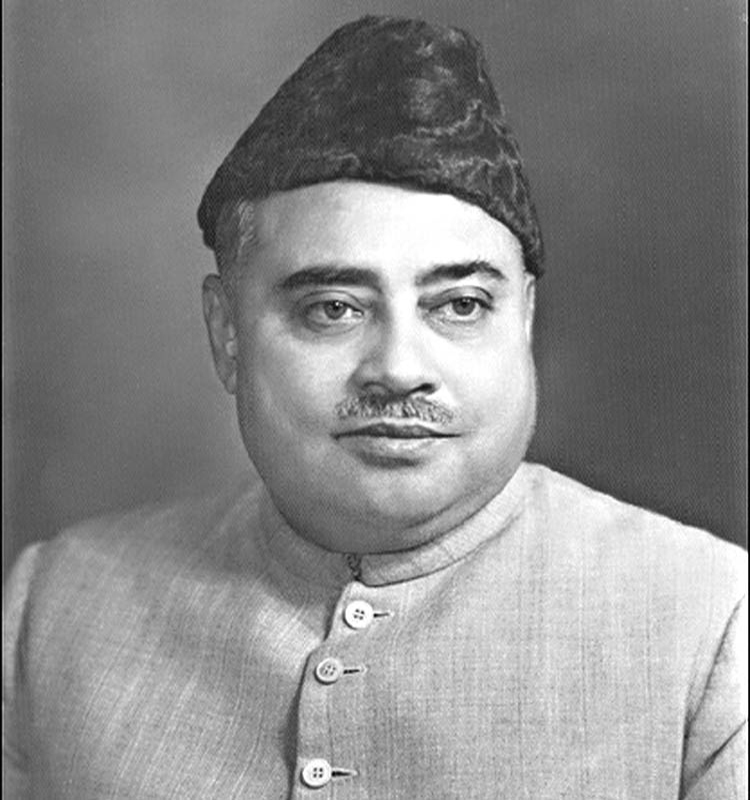

A direct descendant of the Prophet Muhammad whose family settled in Bengal as Sufi saints, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy was a pre-Partition organizer for the Muslims of Bengal, a pioneering leader of Pakistan serving as fifth Prime Minister, the founder of the still-ruling Awami League Party and the father of Pakistan’s nuclear program.

How exactly his family settled and made a home in Bengal for over 900 years and how he himself was so uniquely positioned and accomplished in the history of the Indian subcontinent, are two tales that meant to be re-told for the continued gratitude and guidance for South Asians, Bengalis, Muslims, Indians, Pakistanis and Bangladeshis alike.

Suhrawardy lived during a time where he carried all these labels—as a Bengali politician during the Indian Independence movement, Partition and the first fifteen years of Pakistan. Born into a family of immense privilege during the turning point of Bengal’s history, Suhrawardy leveraged his education and career as a lawyer, union leader and politician to serve the underprivileged Muslims of Bengal and later, the Hindus of Pakistan.

“Shaheed Suhrawardy Zindabad!” (Long Live Shaheed Suhrawardy!) were frequent slogans shouted by Bengalis in both British India and later Pakistan ever since Suhrawardy’s first elections in the 1930s. Just a decade before his 1956 state visit to the U.S. as Prime Minister of Pakistan, Suhrawardy was victorious in the 1946 general elections during the final year of British India which secured a mandate for Pakistan’s founding. In the decade prior in the 1937 Bengal Provincial Elections, he led the Muslim League to victory in Bengal which ushered in drastically needed socioeconomic reforms for the Muslims of Bengal. Before taking office as Prime Minister of Pakistan, Suhrawardy had already been the founder of Pakistan’s first opposition party (the Awami League), Chief Minister and Prime Minister of Undivided Bengal and the greatest lawyer in Pakistan.

A lifelong fighter for the Muslims of India and later Hindus of Pakistan, Suhrawardy was one of the great leaders of Bengal, India and Pakistan, taking a leading role in the politics of the subcontinent during and shortly after the fall of the British Raj. His education, life and legacy live on today through Pakistan’s foreign policy, India’s partition history and Bangladesh’s still-ruling Awami League Party—which he is the founding architect of.

Within pre-Partition Bengal and later Pakistan, Suhrawardy’s enmity with both the Bengali Hindu elites that would later mobilize against his idea of a United Bengal and the Pakistani military-bureaucratic elite that would impose the first military coup under his watch, foretell the relationship that newly independent Bangladesh would adopt with West Bengal and Pakistan. Tracing the footsteps of Bengal’s top Muslim League politician and Pakistan’s first successful opposition leader, we encounter not only the borders and roots of the reigning political party in Bangladesh, but the struggles that shape how the people of Bangladesh grew out of British India and Pakistan.

Whether in the courtroom or in rallies, Suhrawardy was a powerfully persuasive public speaker which made him and the popular forces he led invincible in free and fair elections (1946 All Bengal Elections & 1954 East Bengal Elections). Recognition of Suhrawardy’s invincibility in the polls by Pakistan’s military bureaucratic elite would later drive the same elites to overthrow the civilian government with a coup and impose Martial Law in 1958 in order to preempt the general elections scheduled for early 1959. The end of Suhrawardy’s stellar career with Pakistan’s first coup, was as tragic as his political scapegoating by Indian vested interests for the 1946 Calcutta riots and his fall from grace in Bangladesh for falling short on his 1954 Jukto Front election promises.

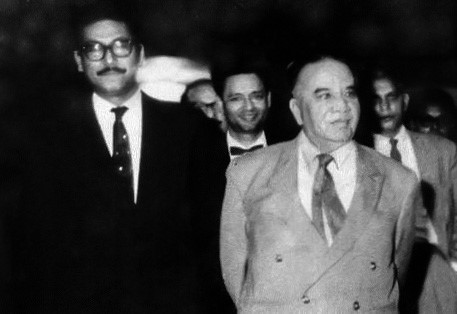

Suhrawardy ultimately lived beyond his death through his favorite political lieutenant, the future Founder of Bangladesh, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, whom Suhrawardy first met in 1937 as a cabinet minister on Sher-e-Bangla A.K. Fazlul Haq’s cabinet while touring the Mission High School in Faridpur, where Mujib was an eighteen year old high school student.

Upon deep study of many primary sources of friends, family and foes of Suhrawardy, it is clear that assuming bad intent on behalf of such a tremendous figure is both disingenuous and tends to serve the interests of whoever is charging Suhrawardy with historical injustices. Suhrawardy ruled in three countries during the crucial Independence era, upholding democracy, the rule of law and diplomacy, but his policy decisions resulted in him being hated in some circles while endlessly adored in others.

The events leading up to and following the Partition of India were some of the most important moments in the history of the Indian subcontinent and Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy was one of the makers of that history.

Born into a Line of Luminaries: The Suhrawardy Family of Bengal

Born in Midnapore, West Bengal in 1892, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy was born into an illustrious Bengali Muslim family with over 900 years of recorded history as Sufi saints, poets, social reformers and politicians.

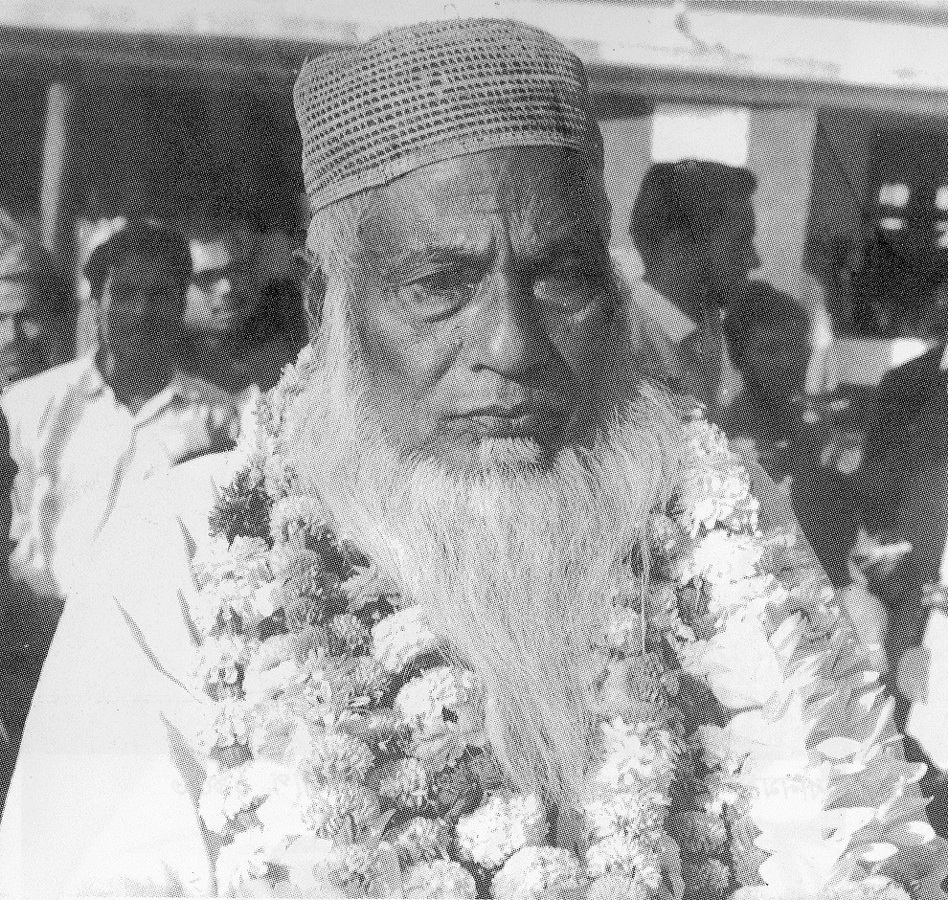

His father, a man of distinguished learning and public service, was Sir Zahid Suhrawardy who served as the Chief Justice of the Calcutta High Court. He was knighted after retiring from the bar and when Zahid Suhrawardy passed away in 1949, the Pakistani English daily Dawn newspaper title read, “The Last Great Gentleman passes in Bengal.”

His mother, the first Muslim woman to pass the Senior Cambridge Examination, was Khujista Banu Suhrawardiyya, an academic fluent in Arabic, Persian, Urdu and English who served as the first Urdu literature examiner at Calcutta University. A veiled woman, Khujista Suhrawardiyya was a lifelong advocate of women’s education and social worker, who regularly visited the slums to provide the poor with education and educate them about health and sanitation.

The Suhrawardy family settled in Bengal when Sheikh Shahabuddin Suhrawardy (1145-1235), a major leader of the Suhrawardiyya Order of Sufism and author of ‘Awarif Al-Ma’arif‘ (Knowledge of the Learned), sent his disciples to spread Islam in Iran, Central Asia, Hindustan and Bengal. Shaikh Suhrawardy is the earliest ancestors of the Suhrawardy family of Bengal, whose ancestral home in the village of Sohraward, Iraq, is where the family gets its Arabic surname from. According to family tradition, Sheikh Suhrawardy’s father descended from Hazrat Abu Bakr Siddique, the first Caliph of Islam, while his mother descended from Hazrat Ali Abu Talib, the fourth Caliph of Islam and son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad. Therefore, Suhrawardy was both a Sayyid (an Islamic nobility status conferred to the direct descendants of Abu Bakr) and a Siddique (an Islamic nobility status conferred to the direct descendants of Ali).

These are ultimately caste labels that allowed the Suhrawardy family members to receive immense socioeconomic, vocational and educational benefits, simply through recognition of family lineage. In the era of Muslim rule in South Asia, upper caste Muslims or ashraf Muslims were settlers who descended from Muslim settlers during the Sultanate and Mughal era including Turks, Arabs, Afghans, Mughals or people of Iranian descent, while native converts into Islam were considered lower caste or ajlaf Muslims. The Suhrawardys were clear ashraf Muslims claiming descent from the first caliph of Islam, whose nobility was recognized as sufi leaders in the Court of Alauddin Khilji in 13th century Delhi just as well as it was in Bangladesh and Pakistan, where streets, parks, hospitals, sports stadiums and a medical college are named after Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy.

However, lineage itself didn’t carry the weight of their name. The Suhrawardys’ actions did.

The Suhrawardys were actually the first Sufi order to arrive in the Indian subcontinent, before the Chishti Order, with Maulana Rukunuddin Suhrawardy being received by Sultan Alauddin Khilji in Delhi, kissing his feet upon their encounter. Hazrat Shah Jalal, the famous Sufi mystic who settled in Sylhet with over 360 followers in 1360, also belonged to this illustrious family. In West Bengal, the name of Maulana Obaidullah Suhrawardy (1834-1886) carries much reverence due to his pioneering role in the Islamic Renaissance movement in Bengal. Known as Behr-ul-Uloom (Ocean of Knowledge) for his vast knowledge as a linguist and educationalist, Maulana Obaidullah Suhrawardy established himself in Bengal as the first superintendent of the Dhaka Aliya Madrasa—which was the only institute in Eastern Bengal when it was founded on March 16, 1874, that taught English to Muslim students.

Suhrawardy’s elder and only brother, Professor Hassan Shahid Suhrawardy, was a notable linguist and art critic who continued his studies in Russia following his graduation from Oxford in 1913. He was well-liked in Moscow and received his first teaching position as Professor of English at Moscow University. Escaping with Russian refugees during the Russian Revolution of 1922, he later returned to Kolkata as a Professor of Fine Arts at Calcutta University.

Suhrawardy’s older brother was known affectionately as “Shahid Bhai,” while Suhrawardy himself was referred to as “Shaheed Bhai.” The two were the complete opposite in nature: Shahid was a quiet soul who enjoyed solitude and soft classical music, while Shaheed felt more at home in the middle of a crowd and enjoyed loud jazz music. Shahid found jazz music repulsive, always reminding Shaheed of his distaste towards it. “Shaheed Miya, please turn off that infernal din,” Shahid would request; to which Shaheed would slowly tone down his jazz music. More so, Shahid found politics to be much too vulgar for his liking. The two got along beautifully, once even moving back in with each other when Shahid was back teaching in Calcutta and Shaheed was active in the Muslim League.

The two grew up in a loving home surrounded by family with towering pedigrees and professional reputations as well as a Bengali Muslim community that their ancestors lived among for generations. On occasions like Eid, the Suhrawardy household was brimming with people and aromas of all the Bengali dishes like halwa and savian, which Shaheed was always there to taste. Shaheed was a stern and unemotional, yet endlessly sociable young boy. From a young age, he was undeniably of gifted intellect and an even greater affinity for controlling and commanding crowds—whether in his hometown of Midnapore, London, Kolkata, Karachi or Dhaka.

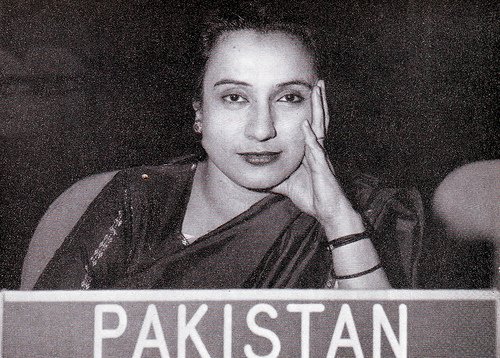

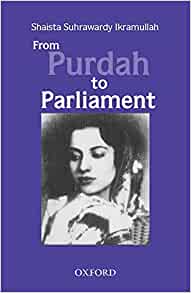

Shaheed would playfully grab the plaits of his younger cousin, Shaista Suhrawardy Ikramullah, who would grow up to be a lifelong intellectual and political ally of Shaheed as the first Pakistani woman to be elected to the Pakistan Constituent Assembly in 1948 and later Ambassador to Morocco between 1964 and 1967. Shaista was also the first Muslim woman to receive a PhD from the University of London in 1940 and would go on to lead a pioneering career as a woman in public service in newly established Pakistan.

As a delegate to the United Nations in 1948, Shaista was the only Muslim and, besides Eleanor Roosevelt, the only other woman to help draft the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Shaista was a major advocate of freedom, equality and choice in the Declaration. She personally championed the inclusion of Article 16, on equal rights within marriage, which she believed was a universal method of combatting forced and child marriage. Being one of two women elected to serve on the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan in 1947, Shaista was one of Pakistan’s first politicians to advocate for her Bengali constituents, human rights and rights of religious minorities. Shaista’s most important accomplishment in Pakistan politics was her 1951 passage of personal laws guaranteeing Pakistani women the full inheritance rights against the wishes to traditionalists at the time.

Her autobiography, From Purdah to Parliament, tells the story of her life reflecting as one of the first South Asian Muslim women to leave purdah (the South Asian practice of women staying out of the view of men) and pursue not only a phenomenal education, but play an active role within the Indian Independence movement, Pakistan movement and later Constituent Assembly of Pakistan. Suhrawardy lived in a happy and highly educated home, surrounded by a community both in awe and appreciation of the Suhrawardy’s legacy and continuous contribution to the livelihood of Bengali Muslims during the British period.

Suhrawardy himself, just as many of his family members, gave great heedance to their family name because “it played a very important part in the molding of his character and values.” In the words of Shaista Suhrawardy Ikramullah, “All of us of that generation, despite our best efforts to belittle it, felt the weight and the obligation of the family tradition which shaped our characters and fashioned our destinies, and because of it others seemed to regard us as a people apart and accepted much from us because we were Suhrawardys.”

Even when Shaista’s family would visit Dhaka after Partition from their home in Karachi, she would warn her kids of mischief by reminding them, “every stick and stone there knows us.”

Ultimately, the point to be made regarding Suhrawardy’s lineage is that his family directly benefited, in both repute, caste and socioeconomic mobility, from birth into this distinguished line of learned public servants and saints, renowned for their learning and piety rather than wealth, because as Shaista Suhrawardy Ikramullah mentions, “wealth is reckoned.”

From Bengal to Britain: Young Shaheed learns the Ropes

Suhrawardy received his early education from his mother and maternal uncle, Sir Abdullah al-Mamun Suhrawardy, who was awarded the first PhD from Calcutta University for his dissertation on the Sources of Muslim Laws. While he spoke Urdu at home, where poetry from Ghalib, Urfi and Kabir filled the bookshelves alongside Western classics from Milton, Marlowe and Shakespeare, he excelled in Arabic and English in the classroom. He enrolled in the Calcutta Aliya Madrasa and graduated with honours in science from St. Xavier’s College. In fulfillment of his mother’s wishes, Suhrawardy also completed a Master of Arts in Arabic from Calcutta University in 1913.

During the same year in 1913, he left Kolkata for England in pursuit of higher studies, graduating in science with honors from Oxford University. Suhrawardy, having also completed a BCL law degree from Oxford, was called to the Bar from Grey’s Inn in 1918. Having attained such a phenomenal education, a brilliant career was prophesied for Suhrawardy. However, he withdrew from a comfortable life of the bar in London and instead set his sights on politics of his homeland of Bengal. Living and studying in his family home in London between 1913 and 1920, Suhrawardy became involved in the Oxford Majlis, where he met Muslims students at Oxford from all over the world to debate and collaborate on issues such as the growing Indian Independence movement. In fact, when Suhrawardy’s older brother was studying at Oxford in 1913, he happened to be a student when Tagore became the first non-European to be awarded a Nobel Peace Prize and was also received by the Oxford Majlis.

When Suhrawardy returned home from London to Kolkata in 1920, he married Begum Naiz Fatima, the daughter of Sir Abdur Rahim, a judge of the Calcutta High Court. Together, they had a son and a daughter. Their son, Shahab Suhrawardy, died early in 1940, while pursuing his studies during his second year at Christ Church in Oxford which devastated Suhrawardy. Shahab’s death marked a dark point in Suhrawardy’s life where the crushing loss of his son made him seem like he aged twenty years while he was tirelessly organizing the Muslim League for the next half decade till the birth of Pakistan.

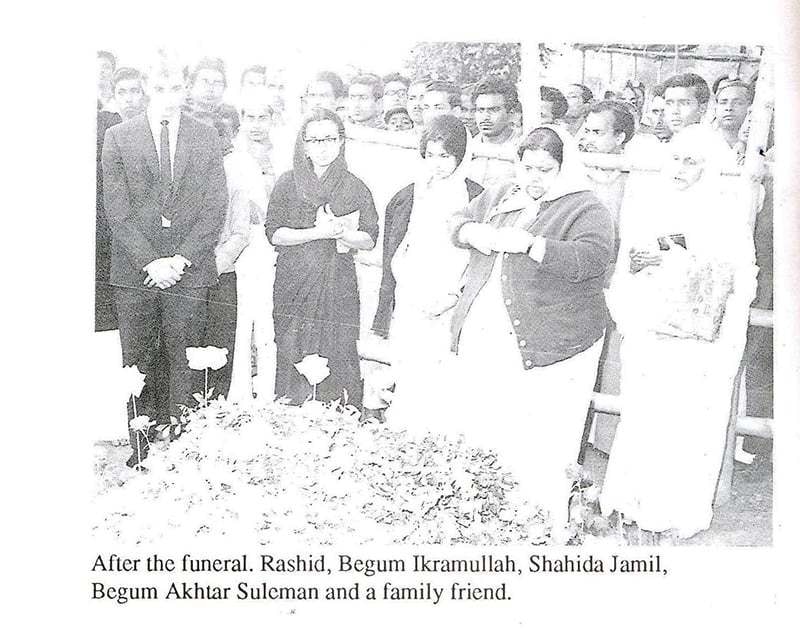

Their daughter, Begum Akhtar Suleiman, married Sir Shah Ahmed Suleman who was son of an esteemed judge at the Calcutta High Court, Justice Sir Shah Mohammad Suleman. Suhrawardy treated Suleman as a son and he always found warmth in the comfort of his daughter’s family–even taking his daughter to the U.S. during his 1956 state visit as Prime Minister of Pakistan. When Begum Akhtar’s father-in-law died, Suhrawardy would stay with them at their home. However, this was no substitute for having a family of his own at home and this was a comfort he never knew partially due to the nature of his work.

Suhrawardy would marry again to a Russian actress of Polish descent named Vera Alexandrovna Tischenko in 1940. They had one son together named Rashid Suhrawardy, a British actor, who later picked up the acting name Robert Ashby. Rashid was Suhrawardy’s only surviving son, who recently passed away on February 7, 2019, kept very close ties with Bangladeshi leading politicians, academics and prominent figures and was himself a lifelong supporter of Bangladesh.

As a lawyer, Suhrawardy was a natural ace. Before Partition, when he practiced law in Kolkata, his clients ranged from everyday people, labor unions and Khilafat members. While in office, Suhrawardy would work 18 to 20 hours a day. After Partition, when he practiced law in Pakistan, his clients ranged from Muslim League leaders wrongfully charged with treason, Pakistani generals during the Rawalpindi Controversy and himself, when he was slapped with EBDO orders by Ayub Khan.

His warm personality and baritone voice made him a pleasant presence, while also being a devastating legal practitioner. Never attacking his opponents or believing in political vindictiveness, Suhrawardy respectfully addressed his opponents as well as allies as family over a fire-side chat–even in the heat of argument. One courtroom adversary of Suhrawardy remarked about how legal arguments with Suhrawardy felt as if inanimate objects such as chairs and tables were also witnesses against you. This was the gift of gab and showmanship Suhrawardy possessed after completing all those years of his precious education at home and abroad. In Suhrawardy’s letters, legal transcripts and personal letters, there remains a consistent tone of strong commanding language accompanied with kind greetings and moral rectitude—whether he was addressing his arch-rival and the first Pakistani military dictator Ayub Khan from prison or his own niece, Salma Sobhan, for not being able to make her wedding because of Suhrawardy’s imprisonment. Suhrawardy’s restraint and standard of due respect to both ally and adversary, was admired as much as it was feared.

The Calcutta High Court, where Suhrawardy and many of Bengal’s legal eagles would advocate and defend in court, became a public spectacle where masses of Kolkata would flock to court just to witness Suhrawardy make his case. Whether it was acquitting leaders of the Khilafat movement or innocent Muslims wrongfully jailed during the 1926 Calcutta Riots, Suhrawardy was always there and afterwards, people never failed to remind others how Suhrawardy saved them from the gallows.

Public service didn’t end in the courtroom for the talented Suhrawardy. He would soon find himself joining the Swaraj Party and later leading the Muslim Struggle alongside his uncles and many Bengali Independence luminaries of the 1920s and 40s including Chittaranjan Das, A.K. Fazlul Haq, Khwaja Nazimuddin and Maulana Abdul Hamid Bhashani. It was during this time that Suhrawardy decided to learn Bangla in order to better mobilize the Muslim masses of Bengal, who he hoped to represent and reorganize before the eve of Independence. As a native Urdu speaker, as many of the Muslims of Kolkata are historically, he picked up Bangla to better relate to the people he wished to represent. He learned the importance of close affiliation with his constituents after Khwaja Nazimuddin, a lifelong rival from a zamindar family within both the Muslim League and later Pakistan, was unseated in his own zamindar, demonstrating how ashraf Bengali Muslims could be both isolated and out of touch as a result of their caste privilege among Bengali Muslim masses.

In the words of Suhrawardy himself, “the fact that I am Bengali is just as true as the fact that I am a Muslim.” Suhrawardy would speak his quickly acquired Bangla for the next twenty years of his political career, whether during his speeches during the 1954 Pakistan General elections or when meeting eighteen-year old Mujib while touring his high school in Faridpur in 1937.

Tofazzul Isam aka ‘Manik Mia’, one of East Pakistan’s then-top political thinkers and Editor of Ittefaq, one of Bengal’s daily, remarked about Suhrawardy:

“Generally, rich people avoid and forget their poor relatives. But it was different with Shaheed Suhrawardy. He searched them out, visited their cottages, never hesitated to have meals with them and helped them generously. He could mix with the common people—slum dwellers, workers, laborers and peasants—to create confidence in them as easily as he trod among the statesmen of the world to explain Pakistan’s bonafides.”

With the gift of humility and empathy, while armed with the education and bravery to command the destiny of Bengal, Suhrawardy embarked on a forty year career in public service that would shape three countries. He kept his easy-going and warm personality to his last breath.

Entry into Politics: Shaheed joins the Muslim Struggle

1920 was a turbulent year in the Indian subcontinent. Three movements were shaping the social environment and Suhrawardy would join the fight in all three.

First, the rapidly deteriorating relationship between the upper-caste Bengali Hindus in better socioeconomic conditions and the larger and largely agriculturalist Bengali Muslim and lower-caste Hindu communities were coming to a tipping point. Kolkata was soon to become a killing field, where a century of communal hatred would play out.

Second, the All-India Muslim League party started in Dhaka in 1906 to protect Muslim interests in Bengal was losing influence and being reduced to a few Western arm-chair politicians.

Lastly, World War I (1914-1919) had come to a close and with it, the Ottoman Caliphate was on the verge of abolishment and separation from its former territories in the Middle East, North Africa and East Africa. To Muslims in British India, it was seen as the fall of the last Islamic power they looked to for a source of pride. In Bengal, as well as throughout the Indian subcontinent, Muslims rose in solidarity and revolt through the Khilafat Movement against the British at home for its part in the collapse of the Ottoman Empire.

Between 1919 and 1922, the emotional fervor felt by Muslims for the unconditional overthrow of the British Raj was endorsed by Gandhi as well, who applied a doctrine of noncooperation to protest against the British. Thousands of underpaid clerks left work alongside tens of thousands of students, while the Indian National Congress party boycotted British goods—namely textiles as their second most effective weapon. The streets of British India were filled with tremendous energy as every street corner had poems read enforcing this doctrine and expressing the need to fight in unison with Turkey. One such poem from this moment was the epic poem “Kemal Pasha” written by the Bengali rebel poet, Kazi Nazrul Islam, in honor of Turkish Republic Founder, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk.

Suhrawardy came home from Britain to a Bengal where the Khilafat movement and further socio economic problems were daily news. Many members of the Khilafat movement, such as Maulana Muhammad Ali, Maulana Shoukat Ali, Maulana Hazrat Mohani and Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, had all been incarcerated. Pictures in the newspapers showed these renowned and courageous Muslim leaders unceremoniously marched wearing the garb of ordinary prisoners of the British Raj, where the prison uniform included half-sleeve shirts and shorts—a form of dress that prevented them from performing their prayers. Khilafat leaders were subjected to the indignity of wearing prison clothes that brought British India to an extremely dangerous point through clashing religion and politics.

Suhrawardy and his two uncles gave passionate speeches attacking the treatment of the prisoners, which was aimed at the current Home Minister, Sir Abdur Rahim, Suhrawardy’s father-in-law. The ordeal was so condemning that Suhrawardy himself thought it best not to visit his in-laws, who would raise his children even after his wife’s death, separating his family from that point on.

Forming several Bengali Muslim political groups, Suhrawardy helped establish the Calcutta Khilafat Committee during the Turkish War of Independence and impending dissolution of the Ottoman Caliphate.

Additionally, Suhrawardy made his official entry into politics with the Swaraj movement. Swaraj, meaning self-rule, was the preeminent Indian Independence movement started by Maharishi Dayanand Saraswati in 1876, when he first gave the call for Swaraj as “India for Indians.” In the 1920s, the prevailing All-India Congress under Gandhi had split into the Swaraj Party led by Motilal Nehru in North India and Chittaranjan Das in Bengal.

In 1923, Das entered into a pact with other Muslim leaders of Bengal known as the Bengal Pact, which afforded Muslims of Bengal separate representation through separate electorates on the basis of population. According to the Pact, Muslims of Bengal would get 55% of government appointments until a time came where the disparity between Hindus disappeared. Additionally, the position of Mayor of Calcutta would alternate between a Muslim and a Hindu every three years and the Calcutta Corporation, originally a monopoly for Hindus, had seats reserved for Muslims.

Das was a symbol of Hindu-Muslim unity, who Suhrawardy deeply respected and believed that had he lived beyond 1925, Bengal would have possibly avoided Partition. To Suhrawardy, Das was a magnificent statesman and also the only Hindu in the forefront of politics who believed that without Hindu-Muslim understanding, there could never be solutions to the many problems the country faced. In Suhrawardy’s own words, Das was “the greatest Bengali” and his loving political mentor.

Beyond the backdrop of the Khilafat movement was the much harsher reality of the extremely poor position Muslims were in all throughout the Indian subcontinent.

Following the fall of the Mughals, historic and economic factors usurped Muslims from their ruling class status which they enjoyed for 551 years. The Mughal ruling class of Bengal were descendants of Mughal court officials or commanders in the Mughal army with no ties to the land. While the elites gradually disintegrated with the rise of the East India Company, the majority of Bengal’s population were Muslim converts from Hinduism seeking to escape caste oppression. Largely agricultural laborers, the Bengali Muslim masses faced impoverishment after the East India Company passed the Regulating Act of 1773 after ruthlessly extracting from Bengal for 16 years. This Permanent Settlement’s indiscriminate land resumption turned thousands into landless laborers, while elevating the Hindu debt collector at the expense of the Muslim landlord and peasant.

The result of the Permanent Settlement Act and the overall air of suspicion and distrust Muslims were treated with throughout the Indian subcontinent due to their more prominent role in the 1857 First Indian War of Independence. Even a century after the East India Company’s first victory and foothold in Bengal, the shadowy presence of a Muslim emperor ruling India had inspired soldiers within the rank of the East India Company to revolt. Describing the relative position of Hindu and Muslims in newly established British India, in the words of Scottish historian and member of the Indian Civil Service, William Wilson Hunter:

” The power had virtually passed into British hands after the Battle of Plassey in 1757, but the shadowy figure of the Muslim Emperor continued to remain in the Red Fort of Delhi, and the fiction of his rule was maintained by the meticulous observance of protocol. The Mutiny of 1857, put an end to this game of make-believe, it dealt a shattering blow to the Muslims of India, their pride humbled, their prestige as a ruling class laid in dust. For the Hindus it merely meant a change of masters, for the Muslims it meant becoming the ruled instead of the rulers.

Hunter’s Mussalmans of Bengal (1871)

Whereas during the Mughal era, Dhaka was a hub for commerce, industry and trade; during the British era, the former fishing village turned second city of Empire by the British of Calcutta would assume the new role as center of Bengal’s economic, political and financial activity. Additionally, West Bengal’s first university established in 1817, while Bangladesh’s first university was founded in 1912, further demonstrates the hegemony that focused on Calcutta as the core of Bengal, devoid of Muslim masses and their loyalties to a former era.

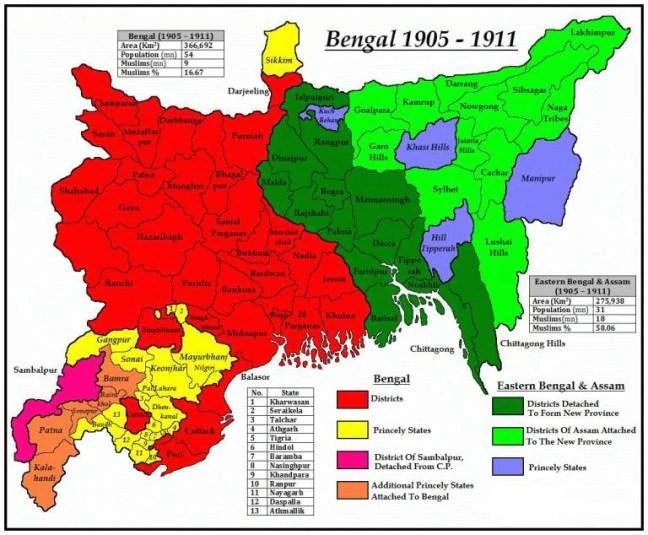

Muslim interests finally united and formed a platform in 1906 at the venue of the Ahsan Manzil in Dhaka, the royal residence of the Nawab of Dhaka. A party comprised of Muslim landlords, nawabs, businessmen and other leading figures established the All India Muslim League in response to the 1905 Bengal Partition, where the British Empire partitioned the first border between East and West Bengal.

This was seen by Bengalis as an attempt to consolidate the industrial and academic institutions of Kolkata in Hindu-majority West Bengal to the detriment of Muslim-majority East Bengal as punishment for rebel activity against the British. The Muslim League sought to safeguard the interests of Muslims throughout the South Asian subcontinent by organizing for the creation of an independent state separate within British Indian territory as a homeland for Muslims in the South Asian subcontinent.

However, Muslims weren’t alone in organizing the need to promote their pan-Indian interests in the form of a political party after the 1905 Bengal Partition, as the Hindu Mahasabha rose in opposition in order to safeguard the Hindu interests. The Hindu Mahsabha similarly sought out economic prosperity, political representation and social harmony for Hindu community members. In the ranks of the Hindu Mahasabha’s upper echelons included Hindutva ideology founder Vinayak Davodar Savarkar and Bharatiya Jana Sangh founder Syama Prasad Mukherjee, a Bengali Brahmin contemporary of Suhrawardy who would lead the charge against the United Bengal Plan and establish West Bengal as a state within India.

By the eve of the reorganization of the Muslim League in Bengal during the early decades of the twentieth century, between 95-98% of land cultivators were Muslim whereas 99% of moneylenders and 90% of landowners and big zamindars were Hindu. More pressing, most of the agricultural laborers were illiterate, which led to zamindars arbitrarily charging them whatever they wanted, often at exponential rates of exploitation and eventual indentured servitude of the largely Muslim working class of Bengal.

During these crushing times for the Muslims of Bengal, Muslim League organizers like Suhrawardy worked tirelessly. First, Suhrawardy organized over 36 labor unions for the working-class, urban Muslims of Kolkata. In the words of Suhrawardy himself recounting his major contributions in his Memoirs:

“I organized a large number of labor unions and employees unions, some communal and some general, such as seamen, railway employees, jute and cotton mill laborers, rickshaw pullers, hackney carriage and buffalo cart drivers and khansamas (butlers) and at one time had as many as 36 trade unions as members of a Chamber of Labor I had founded to oppose communist labor organizations (I paraded a blue flag in opposition to the Red).”

In 1935, the Government of India Act was passed, which provisioned self-government to elected Indian leaders and allowed provinces the ability to elect Ministers to their Provincial Legislatures. After this act, Suhrawardy founded the Independent Muslim Party to fight in elections in Bengal, organizing Muslims based on a membership fee of two annas. Making his political fort in Calcutta, the nerve center of Indian politics, he organized a tabligh, ashura and numerous conferences to draw public support for independence. At the same time, Muhammad Ali Jinnah had recently returned to India from London with hopes of taking charge of the Muslim League as a mass organization with a membership fee of two annas as well.

“I organized a large number of labor unions and employees unions, some communal and some general, such as seamen, railway employees, jute and cotton mill laborers, rickshaw pullers, hackney carriage and buffalo cart drivers and khansamas (butlers) and at one time had as many as 36 trade unions as members of a Chamber of Labor I had founded to oppose communist labor organizations (I paraded a blue flag in opposition to the Red).”

Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy regarding his early organizing with Kolkata labor unions

Before the crucial 1937 elections, the Muslim League in Bengal was reduced to a couple of arm-chair politicians and a prominent son of the soil in East Bengal, A.K. Fazlul Haq, had just recently broken away from the Muslim League and organized the Krishak Proja Party (KPP), which translates into the ‘Agricultural People’s Party,’ to contest the 1937 elections. A.K. Fazlul Haq was later chosen by Muhammad Ali Jinnah to propose the Pakistan Resolution during a Muslim League meeting on March 23, 1940. In honor of Fazlul Haq’s brilliant advocacy for rural people of East Bengal, he is given the honorific title of “Sher-e-Bangla,” meaning ‘Tiger of Bengal.’

The Muslim business community of Calcutta, led by the Hassan Ispahani, invited Jinnah and confided within him their fear that the Muslim League had no future in Bengal without Suhrawardy. Fully aware of the gravity of the situation and heeding the Ispahanis’ advice, Jinnah organized a team including Khwaja Nazimuddin, Abul Hassan, Abdur Rahman Siddique and Hassan Ispahani to persuade Suhrawardy to join the Muslim League.

After initial hesitation, Suhrawardy agreed to join the Muslim League on the basis that is was an All-India organization. In affiliating with the All-India Muslim League with Jinnah as its President, Suhrawardy became the General Secretary of the Bengal Provincial Muslim League (BPML) in 1936. Aga Khan and the New Muslim Majlis led by the Isphanis and now Suhrawardy’s IML all merged with the Muslim League.

The 1937 election was a stand-off between the KPP and BPML for the 119 Muslim seats in a House of 250. The resulting 1937 Proja-League government put Haq as Minister of Labor and Commerce while Suhrawardy would be appointed as Labor Minister.

The Muslim League government’s greatest achievement was the passing of the Bengal Tenancy Act of 1938 and establishment of the Debt Settlement Board. The passing of the Tenancy Act relieved the Muslim middle and working class so greatly that not passing the bill feared “no-rent campaign, coupled with violence and incendiaries, which nothing whatsoever can check.”

To Bengalis, the Muslim League’s ascent and fulfillment of their promise towards the masses represented the first time since Akbar the Great’s annexation of Bengal into the Mughal Empire in 1576, that Bengalis possessed a government of their choice which served their interests effectively.

On another front that would prove itself true a century later, Muslim League leaders gathered in Lahore in order to pass the landmark Lahore Resolution on March 23, 1940, which Sher-e-Bangla A.K. Fazlul Haq presented at the request of Muhammad Ali Jinnah. The Lahore Resolution stated that there were two predominantly sovereign Muslim states within India where Muslims predominated, including Bengal and Assam to the East and Baluchistan, Sindh, Punjab and the Northwest Frontier Provinces (NWFP) to the West.

However, in 1941, Jinnah and Haq had a verbal confrontation after which Haq constituted a second ministry with Hindu Mahasabha leader Syama Prasad Mukherjee, as his deputy.

Everywhere Fazlul Haq went, he was greeted with tomatoes and rotten eggs while black flags were hoisted all around him for his alliance with Mukherjee and the Hindu elite they represented. Taking advantage of the Syama-Haq Ministry’s unpopularity, Suhrawardy and the Muslim League greatly gained influence, but now had to deal with the coming atrocities of World War II and the Partition.

Once in Delhi with his cousin, Shaista Suhrawardy Ikramullah, Suhrawardy was on his way to meeting the Spanish Ambassador after tea with Shaista, when she asked: “Why on earth would you join the Muslim League? You don’t seem like a Muslim League type of person.”

After a brief moment of pause, Suhrawardy responded, “I joined the Muslim League so the Muslims of India are not doomed to remaining the hewers of wood and the drawers of water. I want them to have a chance.” Suhrawardy demonstrated his understanding of a Muslim homeland as a Muslim-majority state in which economic prosperity, political trajectory and minority rights were safeguarded through democratic institutions; not a theocracy that governs, polices and manipulates the population under the guise of religious duty or unity.

This was the voice of the leader of the Muslims of Bengal, who made alliances with whoever he felt at the time had their best interests at heart.

Leading the Charge for Pakistan: Muslim League to Muslim State

After the Calcutta riots of 1926, Suhrawardy grew increasingly disappointed and distrustful of his Hindu colleagues, who he felt showed little regard for the majority Muslims that were killed in the riots. The riots started over legal disputes between Hindus accused of disturbing Muslims by playing loud music near mosques and Muslims accused of slaughtering cows outside of specified areas. Beyond cow slaughter and loud music being played near mosques, was the more pressing tension of Hindu-Muslim socioeconomic class differences.

Muslim laborers came home on the day of the riot to their neighborhoods set ablaze and their families slaughtered, while being met with a majority Hindu police force which arbitrarily imprisoned Muslims during the riots. In the aftermath of the riots, 64 Muslims were indicted with murder charges while only one Hindu was similarly indicted on murder charges during the communal riot. This, in addition to the fact that Hindus constituted 78% of the higher and lower ranks of the Calcutta police, showed that communal tensions were at a fatal tipping point in Calcutta as Muslims were systematically killed and incarcerated.

The spirit of Chittaranjan Das had left with his death, shattering the Hindu-Muslim Unity witnessed in Bengal.

Suhrawardy joined Khwaja Nazimuddin’s Ministry as Civil Supplies Minister on April 24, 1943, following the fall of the Shyama-Haq coalition. World War II was now front and center for British India and Suhrawardy and Nazimuddin were at the helm of Bengal. Bordering British India’s easternmost territory in Bengal, present-day Myanmar was coming under occupation of the Japanese Empire. Japanese forces tacitly approved mass riots in the Arakan state bordering Bengal, where the ethnic Chin and Bamar people were able to attack Rohingya and other South Asian people who were brought into then-British Burma for purposes of helping with the rice cultivation. The Japanese even bombed Kolkata on December 20, 1942 during the heat of World War II.

In response to the threat of a Japanese invasion on British India through Bengal, Nazimuddin and Suhrawardy implemented a scorched earth policy by burning thousands of Bengali fishing boats near Burma to ward them off. While the threat of Japanese invasion during World War II was successfully maneuvered, their tactics of burning fishing boats would contribute to a much larger internal catastrophe—the 1943 Bengal Famine.

The Bengal Famine was initiated by rank incompetency of the British Indian authorities from the year prior. In 1942, the former Prime Minister of Bengal, Fazlul Haq, bought all food grain at high prices, which never dropped. In the Delhi Food Conference in December 1942, Haq assured that there was no potential for food shortage in Bengal, which Suhrawardy vehemently opposed, pointing to a two season failure of crops which actually meant an impending famine was underway. However, as a result of Haq’s assurances, the British Indian government did not make preparations to send food grain to Bengal. In Shaista Suhrawardy Ikramullah’s Biography of Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, she blames black marketers who would hoard food.

Burma’s occupation meant that Bengal’s provincial supplier of food was cut off. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, a close political protégé of Suhrawardy at the time, noted that food grain was not available at the time, even for purchase. Suhrawardy and Nazimuddin’s scorched earth policy destroyed large river crafts which were used for transporting food, while soldiers had priority over food grain and supplementary foods like eggs, chickens, bananas, vegetables, coconuts and pulses due to the policies of Winston Churchill.

Not backing down, Suhrawardy immediately upon taking his oath of office, made a radio broadcast telling his listeners that he feared over 20 million might die because of the failure to secure an arrangement for rice. He promised the people that he would do everything in his power to allocate food grain from other provinces of British India to mitigate the famine. Suhrawardy fought with the central government in order to force the allocation of food grain from surplus provinces such as Assam, Bihar, Orissa and western states such as Punjab with partial success. Bihar, in particular, refused to send any grain which was influenced by the Indian National Congress’s hold over Bihar and contempt toward the Muslim League in spite of the devastation and deaths in the province. Within cities, Suhrawardy commissioned the opening of ration shops for urban residents who could purchase food and free gruel kitchens for mass feeding for poor villagers. Lastly, auxiliary hospitals were commissioned by Suhrawardy to provide medical treatment for famished people and others suffering from diarrhoeal disease.

Despite Suhrawardy’s best efforts and the insufficient support from other provinces, nearly 5 million people died in the 1943 Bengal Famine. This was seen as an artificial killing, blamed on either Churchill for prioritizing food grain for the army or Suhrawardy for not doing enough to address the crisis within his post at the time. The memories, stories and lasting legacy of the 1943 Bengal Famine lives on through the immortalized charcoal sketches of Bangladeshi artist Zainul Abedin.

However, while he would maintain his leadership role over Muslims by complying to join the Muslim League after pressure from Jinnah, Suhrawardy deeply felt tied to Bengal as a whole. On the eve of the 1946 General Elections, Suhrawardy as General Secretary of the Bengal Provincial Muslim League was given the responsibility of organizing the general elections in Bengal. Taking this task on headfirst, Suhrawardy toured the country two decades after his entry into politics; this time going to the most remote parts of the country to mobilize the Muslim masses.

Suhrawardy’s Bengal Provincial Muslim League captured 114 out of 119 Muslim seats of the Provincial Assembly, while Fazlul Haq’s KPP only secured five seats in opposition.

The resounding Muslim League victory in Bengal was a personal triumph for Suhrawardy, who assumed the role of Prime Minister of Bengal. Receiving a personal congratulatory message from Jinnah, Suhrawardy was elected leader on April 3, 1946 and formed his ministry on April 24, 1946.

Bengal’s Muslim League victory not only saved the Muslim League as the only province which voted for it, it saved the party from near extinction, carrying with it the dying dreams of creating Pakistan. The three other Muslim-majority provinces—-Punjab, Sindh and NWFP—-voted against the Muslim League, meaning Bengal served as Jinnah’s only pro-Pakistan province. Jinnah had only succeeded in one out of four Muslim majority provinces, putting Jinnah in an awkward position in convincing the British and Indian National Congress that Muslims of the British Raj wanted Pakistan. Only Bengal served his purpose, although Muslims in the Muslim-minority provinces of the Subcontinent voted solidly for the Muslim League.

In Jinnah’s own words, “Had Suhrawardy not won the general election in 1946, in the light of total failure of the Muslim League in all the other Muslim majority provinces, there would have been no Pakistan.”

The fruits of Suhrawardy’s two decades as an organizer won him, the Muslims of Bengal and future Pakistanis, a guarantee of the inevitable creation of Pakistan. Suhrawardy was the architect of the Muslim League in Bengal, ultimately paving the way for the Partition of India.

Suhrawardy ran the first pre-Partition Muslim League registry in Bengal, which was also the only Muslim League ministry in all of the subcontinent. Suhrawardy’s landmark accomplishment for Pakistan with his Muslim League victory in Bengal, cemented himself as a founding father of Pakistan. His first rural base in politics was in and around Calcutta—through his building organizations with urban workers including jute and textile mill workers, rickshaw pullers and hotel employees.

“Had Suhrawardy not won the general election in 1946, in the light of total failure of the Muslim League in all the other Muslim majority provinces, there would have been no Pakistan”

Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah upon news of Suhrawardy’s 1946 general election victory in Bengal on behalf of the Muslim League.

Following the election, a convention was called by the Muslim League at the suggestion of Suhrawardy on April 7, 1946, at Delhi’s Muhammadan Anglo-Arabic College ground. The convention was meant to discuss the potential of a full Muslim quota on the interim central cabinet after Independence, which Jinnah denied as he was set on the creation of two sovereign Muslim states. Seeing his dream of Pakistan in sight, Jinnah willingly overlooked the geographical separation, differences in lingua franca, customs, social systems, food and dress of the two Pakistans. The only bond between the two to-be wings of Pakistan, was religion.

More importantly, the struggle for Pakistan in Bengal was tied to the Bengali Muslims centuries-long emancipation on not just religious grounds, but economic grounds against the more affluent Hindu zamindar and mahajans that exercised unchecked and total economic control with the fall of the Mughals and the rise of the British East India Company. Suhrawardy was a symbol of not just Muslim unity in Bengal, but of socioeconomic trajectory for the Muslim masses of Bengal and caste liberation.

Suhrawardy’s post-1946 election alignment with Jinnah on a united Pakistan between Bengal and the Western provinces of Punjab, Sindh, Baluchistan and NWFP, questions people to this day. The quick answer is that the greater fear of Hindu domination under the Congress demand for Akhand Bharat (undivided India), pushed Suhrawardy to join Bengal with Jinnah’s Pakistan. Suhrawardy felt that Bengal as an independent, sovereign state, would not sustain itself and find itself playing into Congress hands.

1946 Kolkata Riots

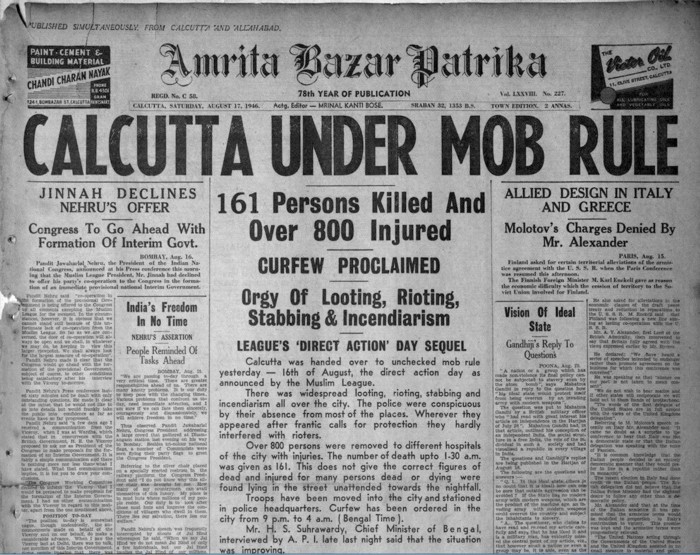

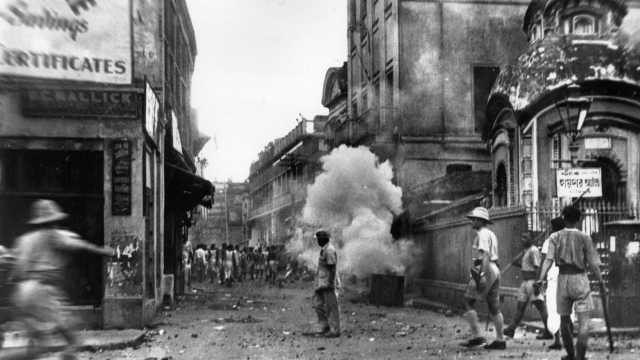

In direct retaliation to the Muslim League, the Viceroy of India which serves as the British Crown’s top representative, General Archibald Wavell, called on the Congress government to launch an interim government which the Muslim League refused to take part in on August 16, 1946. This day in history became marked in blood as Direct Action Day. Muslims of Bengal were expected to have a huge gathering and proclaim their adherence to Pakistan. For this occasion, Suhrawardy declared a holiday on Direct Action Day, which on previous occasions, led to violence between Hindus and Muslims with people being dragged out of their car and assaulted.

Direct Action Day coincided with the holy month of Ramadan, when Muslims were fasting. This holiday was also on a Friday, where Muslims gathered at the mosques in their weekly congregation. Suhrawardy was addressing a crowd at the Ochtierony Monument Maidan where people flocked from all over the city and suburbs, when he heard of obstructions and Muslims being attacked by Hindus in orchestrated anti-Muslim riots.

Calcutta was a city with a population of 6 million at the time, which had a police force of 1,200 of whom, only 63 were Muslim. Among those in the rank of officer, only one Deputy Comissioner and an Officer-in-Charge were Muslim with the remainder Hindus.

Suspecting that the Calcutta police force was both insufficient and questionable in their loyalties and systemic compliance towards anti-Muslim violence, Suhrawardy decided to appoint 1,200 trained Punjabi Muslim sepahis in order to achieve equity in the police force. Hindu leaders opposed and protested this move, urging the Governor to cease the deployment of Punjabi Muslim sepahis and arrange for the same number of Bengali Muslim Sephahis. To this request, Suhrawardy responded that Bengali Muslim sepahis were not readily available as the situation demanded. Additionally, he made the argument that the Calcutta police force was predominantly Sikh, Gurkha, Rajput and Jat, with no Bengali Hindus.

Suhrawardy ordered Muslim Officers-in-Charge to be posted in 21 of 22 thanas (police stations), while he personally operated from the Police Control Room from a British officer to mobilize the police force into quelling the riots. Suhrawardy’s radio broadcast during the riots begins with, “I come in the interest of peace.”

Indeed, Suhrawardy worked tirelessly during the riots to come to the help of anyone and everyone he could. Hassan Ispahani recounts how during the riots, Suhrawardy arranged free lodging and food for many Hindu families and ninety-five Hindu milkmen, in addition to his own barber, Mogen Sheet, and his washerman, Kunja Dhopa. Ispahani mentions, “I have not seen a man work so hard and act so swiftly to try and control a conflagration as Suhrawardy did.”

The riots drew on for four days, causing the Indian Army to be deployed. The British government was drawn to attention and Viceroy Wavell visited Calcutta on August 25 to witness the scene of the carnage.

Wavell was received by a burnt hellscape of a city built by East India Company official, John Charnock, covered in rubble, bodies and thousands of posters condemning Wavell, with his name written in red ink. Wavell asked Suhrawardy how it was that he could be held responsible for the riot?

Suhrawardy explained that this riot was the consequence of the formation of an interim government without proper Muslim League representation and the longer held belief of deliberate creation of Hindu-Muslim misunderstanding as a rationale to hand over power to the Indian National Congress Party.

Suhrawardy doubly warned that what happened in Bengal would repeat itself all over India unless the British realized that a united India was impossible and the Muslim League was essential to save India from impending civil war.

A meeting was held two days later between Jinnah, Suhrawardy and Wavell in order to accept the Muslim League demand. Subsequently, the Muslim League announced their decision to join Pandit Nehru’s interim government on October 15, 1946.

Bathed in the blood of Bengalis, Jinnah accomplished through Calcutta’s riots the guarantee of Pakistan’s birth as a political victory. The 1946 Calcutta Killings became immortalized throughout the subcontinent as the ‘Great Calcutta Killings.’ This momentum for Pakistan under the threat of potential civil war through the Subcontinent, made the inevitability of Pakistan a daily topic of conversation.

As a result the Attlee British government decided on February 24, 1947, that the British would withdraw no later than 1948, with the final partitioning of India being adjudicated to Louis Mountbatten rather than Wavell.

To the detriment of Muslims, Mountbatten had “won the imagination of Nehru” and persisted on the idea of undivided India, which fell on deaf ears with increasing anarchy and threats of rioting. On June 3, 1947, Mountbatten declared a plan to finally partition India and secure a British withdrawal within ten weeks, setting the date of Partition to be August 14, 1947.

Cyrille Radcliffe, a High Court Judge of England, was a personal friend of Jinnah and on their integrity, laid the hopes of the final partitioning of Punjab and Bengal to settle the borders of Pakistan.

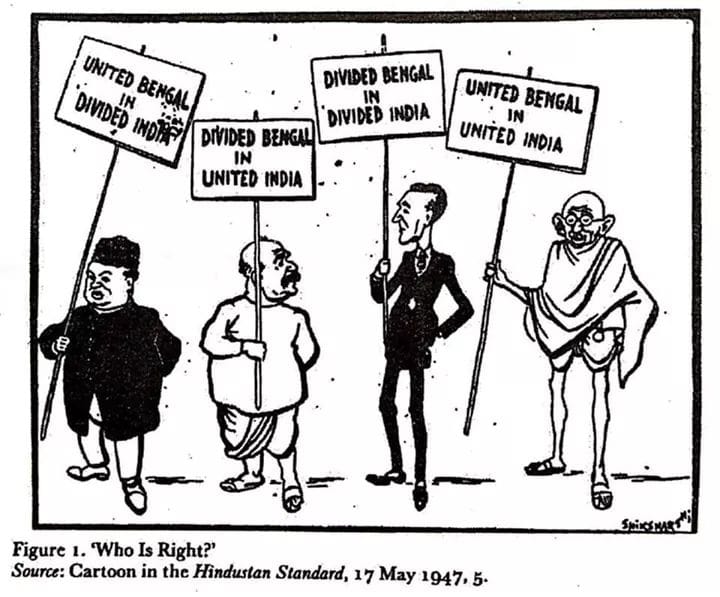

The United Bengal Plan

When the Partition plan was accepted, Suhrawardy rejected the Partition of Bengal particularly on the grounds that all of Bengal was a Muslim majority province. Backing Suhrawardy, Jinnah also professed that on no account would he accept a “mutilated, truncated, moth-eaten Pakistan.” Jinnah once even asked what good was Bengal without Calcutta, given all the industrial and political capital concentrated in West Bengal, while East Bengal was considered a breadbasket.

To prevent the modern-day division of Bengal, Suhrawardy reintroduced his 1933 United Bengal Plan, arguing for an independent, sovereign Bengal as an independent state. While advocates and admirers credit Suhrawardy for the United Bengal Plan, past and present critics on this idea accuse him of the ‘Greater Bengal Scheme.’ The movement for United Bengal was no secret or covert proposal, as Hindu and Muslim politicians across the subcontinent pledged support for this arrangement—showing early resistance against the Two-Nation thesis insisting on two nations within South Asia based on religion hammered down by the British, Indian National Congress and the Muslim League. Given the possibility and trajectory of a United Bengal, it is safe to conclude that a Three-Nation thesis was equally viable for a short period.

In February 1947, Abul Hashim and Sarat Chandra Bose discussed a plan for an independent, sovereign Bengal composed of Bengali-speaking people of Eastern India from Purnea in Bihar to Assam in the further-east. However, immediately upon divulging this plan, the Hindu Mahasabha vehemently rejected this plan entirely and demanded the partition of Bengal with Shyama Prasad Mukherjee at the lead.

He resigned from Nehru’s cabinet after the Nehru-Liaquat pacts and took help from the RSS in order to start the Bharatiya Jana Sangh party, the predecessor to the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

An initial ally and then life-long adversary of Suhrawardy, Syama Prasad Mukherjee is known as the Father of West Bengal. He, like Suhrawardy, grew up in a very privileged Bengali family in Kolkata, whose father was also a Calcutta High Court Justice and who also finished his studies and law degree at Oxford. The only difference was Mukherjee was born into a Bengali Brahmin family, and unlike Chittaranjan Das who enshrined Hindu-Muslim unity in Bengal, Mukherjee promoted division on communal grounds based on fear of further rioting. Mukherjee would become a leading voice of the Hindu Mahasabha.

After witnessing the Noakhali riots of 1946, where Bengalis Hindus in Muslim-majority East Bengal were killed in large numbers in reaction to the Great Calcutta Killings, Mukherjee was set on his resolve for a Bengali Hindu Homeland within the Indian Union. To Mukherjee, a “Hindu could not live with respect in Pakistan,” and the Muslim League desire to incorporate all of Bengal as an independent, sovereign state is actually “a trap of the Muslim League” to make Bengal a Muslim-majority state.

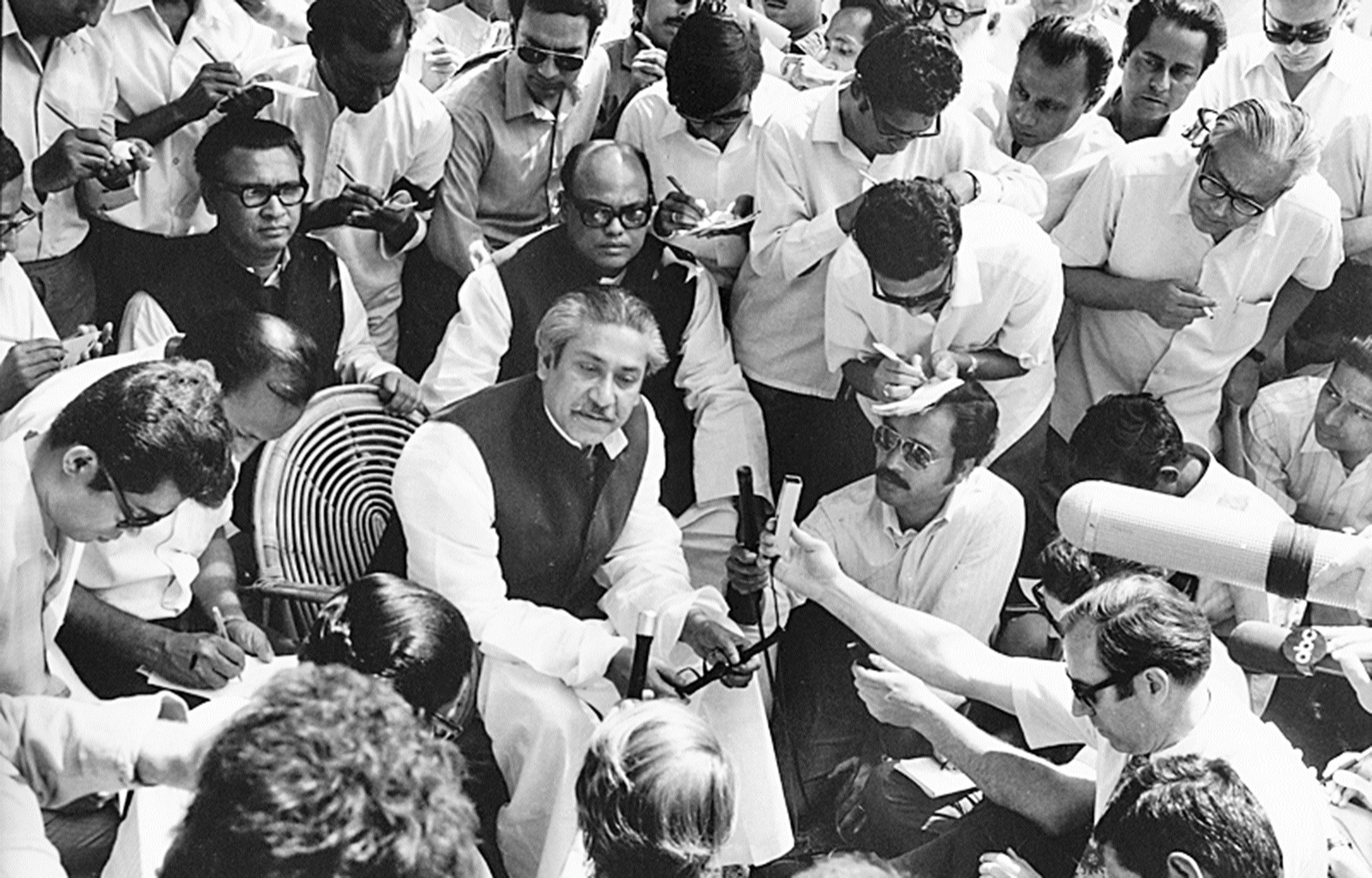

On April 27, 1947, Prime Minister of Undivided Bengal, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, first openly proposed the United Bengal Sovereign State plan at a press conference in Delhi.

“Let us consider for a second the potential of a United Bengal. It will be a great country indeed, the richest and the most prosperous in India, capable of giving people a high standard of living, where a great people will be able to rise to the fullest height of their stature, a land that will truly be plentiful. It will be rich in agriculture, rich in industry, and commerce and in course of time, it will be one of the most powerful and progressive states of the world. If Bengal remains united, this will be no dream, no fantasy.

Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy proposing the United Bengal Plan (Delhi, June 3, 1947)

The Muslim League’s sudden and successful foray into politics, winning in Bengal and establishing the first pre-Partition Ministry in 1946, completely took the Bengali Brahmin Bhadrolok class of Kolkata by surprise. Only two decades ago, they had witnessed the Bengal Pact make breakthrough inclusions of the Muslim community which they then acknowledged had enormous socioeconomic disparities that required addressing. However, to see the same Muslim community form and support a Muslim state throughout India, having won its foothold first and only in Bengal, surely had adverse effects within the Seth, the Bhadrolok class, which Mukherjee successfully manipulated through his Bengali Hindu Homeland Movement.

The overwhelming support against the United Bengal Plan within West Bengal, only put on display the Congress and Hindu Mahasabha’s view towards Muslims.

The final Partition of Bengal was to be a crime which many Bengalis were complicit in, while others considered the alternative of uniting Bengal to be the bigger crime—a sentiment shared by Bengalis to this day. To many, Mukherjee is a divider of Bengal, while others consider Suhrawardy the true divider of Bengal.

Ultimately, in the clash between Suhrawardy and Mukherjee for a United Bengal or a divided Bengal between India and Pakistan, divided Bengal became reality. Mukherjee and the Hindu Mahasabha succeeded in securing a Bengali homeland within the Indian union which we know today as West Bengal, while the remaining territory went to Pakistan.

The two crucial historical moments that define their polarizing, are the 1946 Calcutta riots and Mukherjee’s mustering of the Bengali Hindu Homeland Movement later in 1947 against the proposal of Suhrawardy’s United Bengal Plan.

The Muslim League, being the premier threat to Congress in 1946, was only in power in Bengal. The riots happening under Suhrawardy’s watch, was perfect fodder for the virulently anti-Muslim League Hindu Mahasabha propaganda machine, which aligned with Congress and British interests to shift blame solely on the Muslim League for their collective political gain. The riots were immortalized along with Suhrawardy’s legacy in his hometown of Midnapore, within his own state of West Bengal.

He is remembered in his birth land as the “Butcher of Bengal” for his role as Prime Minister of Bengal during the Calcutta 1946 riots. Suhrawardy had enlisted an additional 1,200 Punjabi Muslim sepahis as a cautionary deterrence measure against a massive anti-Muslim onslaught considering the Calcutta Police Force’s demographics and experience from the 1926 Riots. However, the propaganda machine has embedded their scapegoating and Congress-era villainization of Suhrawardy into the historical memory of West Bengal, painting Suhrawardy as not just complicit but strategically intentional, in the greater scheme of turning Bengal into an independent, Muslim-majority state.

Oftentimes those who believe Suhrawardy divided Bengal, not only believe that Suhrawardy deservedly fits the label of the “Butcher of Bengal,” but also oppose the United Bengal Plan for religious demographic reasons not explicitly mentioned.

This paves the way for those who believe Mukherjee divided Bengal. People who were pro-United Bengal Plan had no reservations towards and were indeed proud of a Muslim League government under Suhrawardy as a landmark indicator of the socioeconomic and political success of the long-stagnant Muslims of Bengal. The United Bengal Plan was the only way to conserve the link between Dhaka and Calcutta, keeping Mother Bengal whole and in one piece.

So when Mukherjee quickly and cleverly organized the Hindu Homeland Movement, the fact that Bengalis themselves would prevent the unity of Bengal was hard to comprehend. However, once pondering the demographic concerns that Kolkata’s new Hindu-majority considered upon thought of a post-Partition, United Bengal, it became clear how self interests played out in the seemingly inevitable partition of Undivided Bengal into West Bengal and East Pakistan. To many, it did not require a moment’s thought to consider why a core of politicians in West Bengal rejected and prevented the possibility of a United Bengal.

A Bengal won, envisioned and predominantly populated by Muslims, was not a Bengal that as Mukherjee put it, could allow “Hindus to live with respect.” This psychology of division glorifies one at the expense of the other and lives on to this day.

Given Bangladesh’s economic trajectory after independence from Pakistan, earning the position of the world’s 41st largest economy with a GDP of $324 billion as of 2021, while West Bengal’s GDP sits at nearly half of Bangladesh at $180 billion with its position as a border state within India, demonstrates that Suhrawardy’s promises proved to true while Mukherjee’s obsessive preservation of a Hindu demographic majority in and around Kolkata, has failed to ensure economic prosperity. The capacity of an independent, sovereign nation-state is clear when considering the paths a once-wealthier West Bengal and a now-wealthier Bangladesh have taken. Although, it should be mentioned that the independence of Bangladesh was not an alternative Suhrawardy would have had hope for and that Awami League offices opened in Kolkata during the 1971 Liberation War aided in the successful independence of Bangladesh.

Suhrawardy was to be the final Prime Minister of Undivided Bengal—-an entity partitioned just as quickly as it was reunited following the 1906 Partition of Bengal. How people can celebrate and appreciate what was initially perceived as an injustice, shows how the last 40 decades of British occupation divided Bengalis in particular.

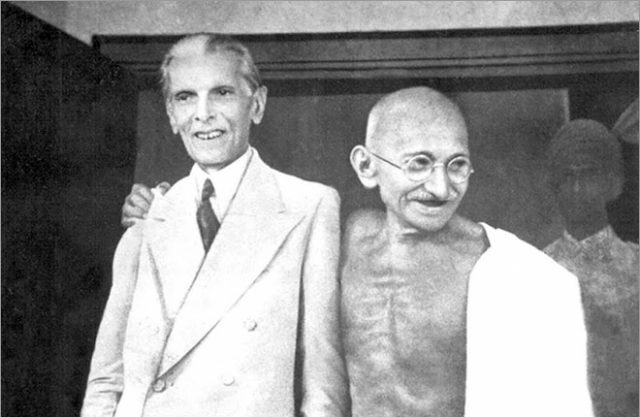

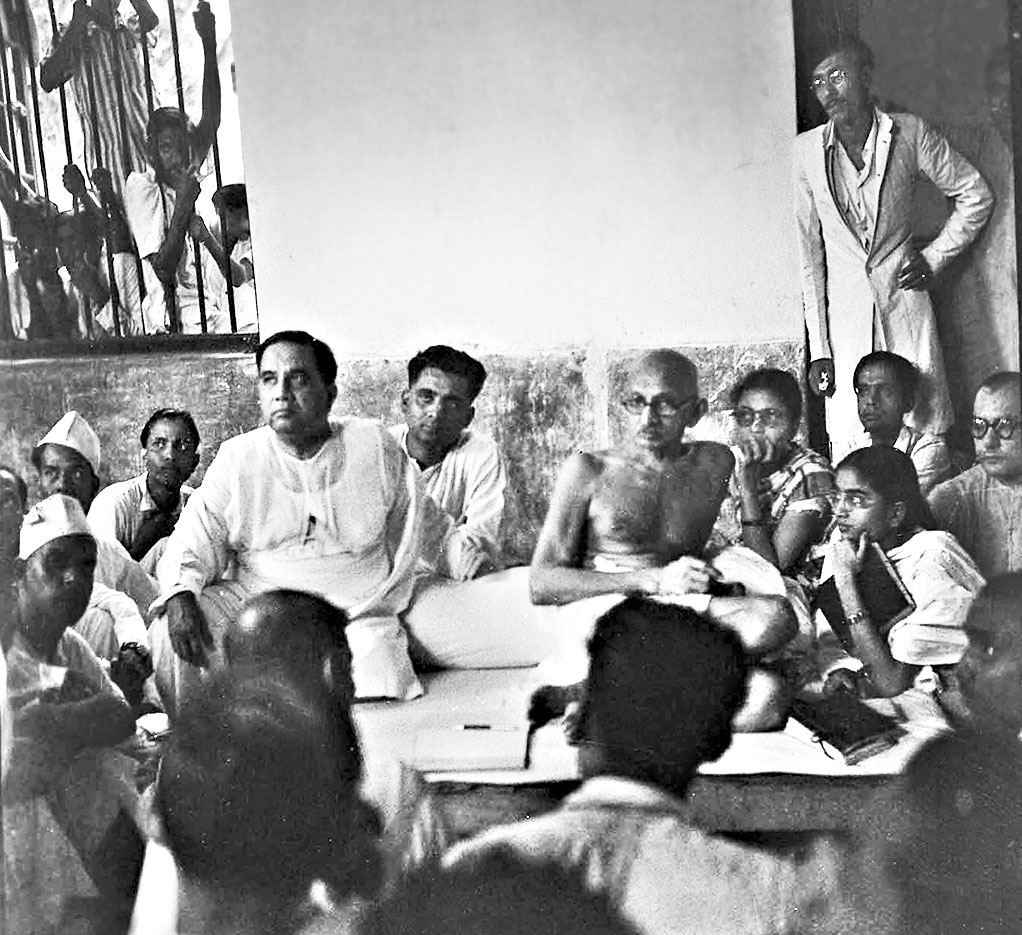

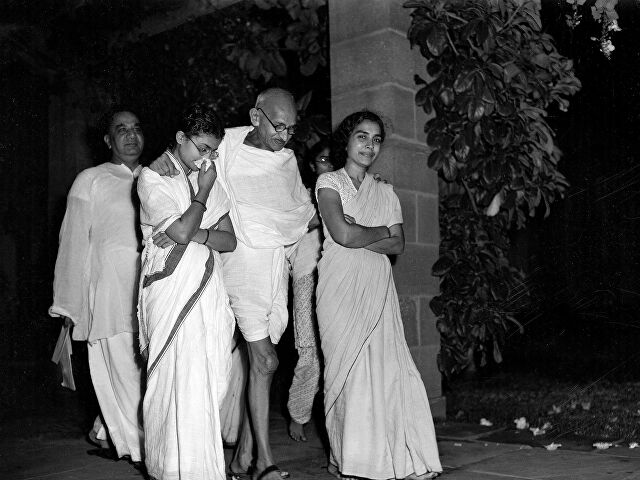

Unfinished Business: Gandhi-Suhrawardy Peace Missions & the Price of Tolerance

After Partition, Suhrawardy’s preoccupation was immediately set on the Muslims of Calcutta. Most, if not all of the Muslims in the Calcutta Police Force, had migrated with their families to East Pakistan, leaving the Muslim population in Kolkata defenseless and terrified. Among the many threats that faced them, were the organized militias of the Rashtrya Syamsevak Sangh (RSS) which had set out to kill both Suhrawardy and Gandhi for their famous peace missions.

According to Shaista Suhrawardy, “he lived like Gandhi, led meetings like Gandhi and even ate like Gandhi and everyone knew how Gandhi ate.” The Peace Missions which had started before Partition, continued even after with Suhrawardy and Gandhi still visiting the sites of communal violence. Risking their lives on every occasion, Gandhi and Suhrawardy were able to quell rioting crowds through sheer force of personality. A while after the Calcutta riots, a crowd incited and screamed at Suhrawardy calling him “the murderer” and “to kill him, Suhrawardy is responsible.” Suhrawardy immediately turned to the crowd and proclaimed, “we are all responsible,” staring the crowd that once looked at him with bloodlust into the broader realization, stopping the riot then and there.

Still, the RSS made clear that Suhrawardy and Gandhi were at the top of their list for bringing the Hindus to nonviolence while Muslims supposedly attacked them defenseless as a result of Gandhi’s peace mission. On one occasion, an RSS assassin was outside a gurudwara where Suhrawardy and Gandhi stayed. Mistaking Suhrawardy, who was in deep meditation at the time, for a monk, the assassin was unsuccessful in murdering Suhrawardy in 1947. Unfortunately for Gandhi, the case was different as an RSS assassin shot Gandhi to death after one of his prayers.

Suhrawardy wished to still run for politics in Pakistan as an Indian citizen, but was unceremoniously vacated from his seat. In newly-created East Pakistan, Suhrawardy’s longtime Bengali Muslim rival, Khwaja Nazimuddin, imposed a ban on his entry into East Pakistan as injurious to public peace, arrested him and ousted him from Dhaka. Nazimuddin also accused Suhrawardy of attempting to unite the two Bengals post-Partition. All of Nazimuddin’s tactics were to prevent a formidable rival in Bengal from challenging him in newly created Pakistan.

In response to these allegations, Suhrawardy held a press conference on June 3, 1948, denying all of Nazimuddin’s charges as baseless and declaring his intention to further the peace mission in East Bengal. Knowing the decades of communal violence which could not devolve any longer, Suhrawardy made his peace missions a priority, regardless of how unpopular it made him in front of his future Pakistani colleagues. Unfortunately, for Suhrawardy, this was exactly what happened as Suhrawardy’s newfound enemies would exploit his advocacy for the Hindus of Pakistan.

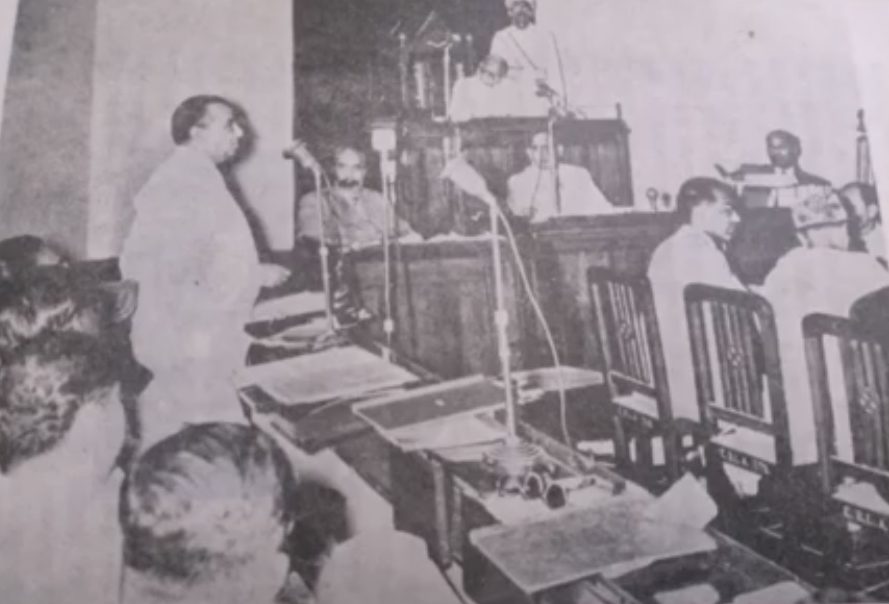

During his first speech before the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan, on March 6, 1948, Suhrawardy made his debut into Pakistani politics. In his speech, he emphasized the rights of minorities within Pakistan and explained how there was no anomaly in speaking at the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan as an Indian citizen.

The impressionable and most unforgettable part of Suhrawardy’s speech was his plea of, “open your heart and mind and take within your fold the non-Muslim minority.” Suhrawardy made an insightful statement, warning the Pakistani government of their communal attitude which urged Hindus to migrate because they no longer felt safe; which also applied to the Muslims of India.

Suhrawardy’s adversaries and the overwhelming core of the Pakistan Constituent Assembly saw this speech as the last straw and considering the successful establishment of Pakistan, considered Suhrawardy’s usefulness to the country to be over then and there.

Within days of his speech, members of the Constituent Assembly considered Suhrawardy to be barred from the Assembly and his seat vacated. While some members objected the move as not just wrong, but illegal considering there were numerous individuals with Indian citizenship serving high government posts in Pakistan such as Mr. Ismail, the High Commissioner of India for Pakistan, and Babu Kumar Chakravarty, a Hindu Member of the Pakistan Constituent Assembly from Calcutta. In fact, only Suhrawardy was subject to such scrutiny over his Indian citizenship, which saddened him a great deal. After much debate within the Assembly, a resolution was passed declaring that anyone who hasn’t taken residence in Pakistan within the last six months, cannot be eligible for a seat on the Constituent Assembly.

Following the resolution, Suhrawardy had decided to move to East Pakistan and use his savings in order to buy a small house in Dhaka. However, when Suhrawardy arrived in Dhaka, East Pakistan in June 1948 by boat in Raniganj, he was served with a notice of extradition within 24 hours, which also prevented his entry for six months. Suhrawardy could not change course and move to West Pakistan, as he didn’t have the funds or any friends in the Western wing to help him settle. Worst of all, Suhrawardy’s father Zahid Suhrawardy, was very sick as he was now 80 years old. As preoccupied with politics as Suhrawardy was, he was deeply loyal to his family and prioritized them before anything else. When Zahid Suhrawardy died in June 1949, the Indian government imposed an exorbitant property tax and later appropriated the 200-year-old Suhrawardy residence on flimsy grounds of non-payment.

Six months expired and on the occasion of the next Constituent Assembly, Suhrawardy’s seat on the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan was declared vacant. Suhrawardy had no choice but to reside in Lahore during the time of his seat’s vacating. Over a decade ago, Suhrawardy was persuaded by a team of Muslim League leaders under orders of Jinnah. According to the Muslim League on the eve of the 1937 elections, there was clearly and undeniably no future for the Muslim League in not just Bengal, but all throughout the Subcontinent without Suhrawardy. Having served and led the Muslim League in Bengal in forming the first Pre-Partition ministry in India, risking his life and earning him notoriety in India, Suhrawardy was now disposable as his accomplishments had already served their purpose.

Pakistan, once envisioned by Jinnah and Suhrawardy, was now at the hands of greedy, fascist politicians as Jinnah died and Liaquat Ali Khan took control.

However, Suhrawardy was no quitter. Even in the face of hypocritical and selective malice aimed specifically towards him by the newborn Pakistani establishment, Suhrawardy refused to resort to petty, personal attacks and instead, diverted his energy towards emerging victorious once again at the polls through the measure of elections. Democracy was Suhrawardy’s realm and it was a realm that Pakistan supposedly aligned itself with upon its founding. Surely, Suhrawardy felt that reclaiming Pakistan to be the nation that he built through free choice and coalitions, was a necessity for not just his career but for the course of Pakistan’s politics in the future.

Before the story is done, Suhrawardy would recoup his political forces, establish Pakistan’s first successful opposition party and become Prime Minister of Pakistan.

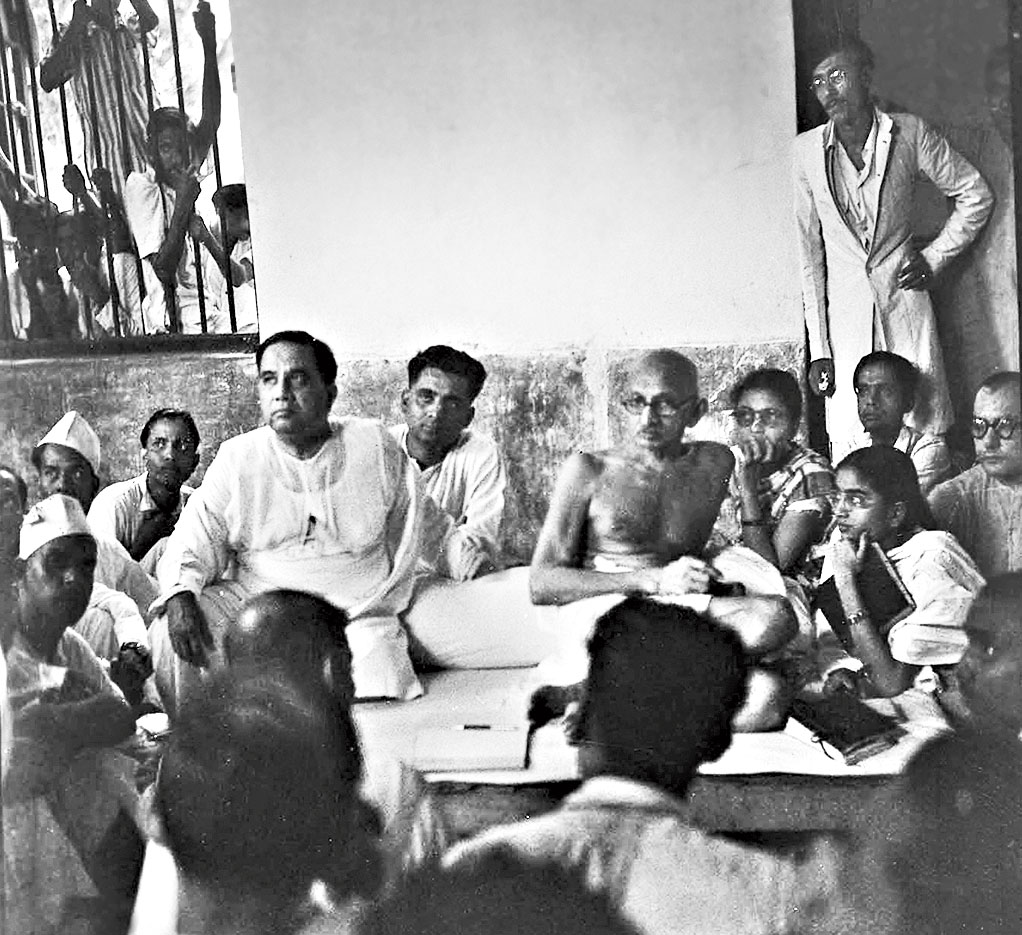

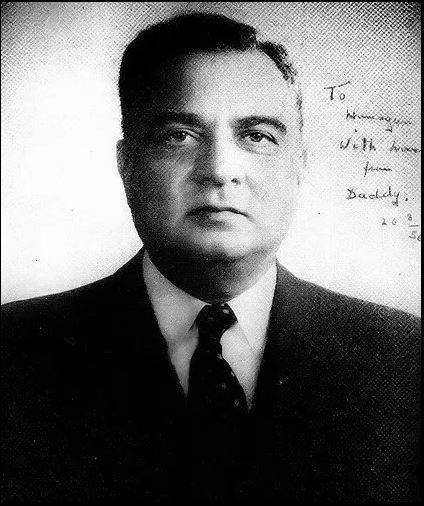

(Margaret Bourke-White, 1946)

Square One Again: An Exile’s Return to the Country he Founded

Suhrawardy arrived in Karachi literally in the clothes he stood in, leaving behind his belongings, family heirlooms, priceless carpets, his record collection, 1947 Buick and the house he grew up in. Undeniably, Suhrawardy was a very privileged and ritzy young man who enjoyed the good things in life—whether they be good cars, good food or good clothes—but ultimately, he was unattached to his material possessions.

After devoting 26 years of his life to defending the interests of Bengal and literally securing the independence of Pakistan, he was not ready to back down before the new Pakistani bureaucratic-military elite.

How exactly Suhrawardy went from the Muslim League politician that saved Pakistan to a targeted political exile, stems from the unchecked political decisions of Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who was now known as “Quaid-e-Azam” for his role as the Founding Father of Pakistan and first Prime Minister.

Jinnah had set Pakistan on a course for military dictatorship and fascism at the hands of the West Pakistan Central Government with the first mistake of appointing his loyal lieutenants as bureaucrats for administration of the new nation. The growth of Pakistan’s bureaucracy seized upon the absence of a powerful political party, as Jinnah’s inexperienced, British-trained bureaucrats assumed total control over Pakistan. Commanding total control of the central government machinery, the bureaucracy not only formulated state policy, but executed it.

More importantly, not a single one of the hundred new Pakistani bureaucrats were Bengali and Jinnah personally avoided appointing a single bureaucrat-turned politicians to a cabinet post from East Bengal. Even though Karachi was the capital of the new nation, Punjabis entitled themselves to the two sources of power in determining the fate of Pakistan—the army and the bureaucracy. Not only had Jinnah forgotten to secure a position for his Muslim League colleague, whom he owed the creation of Pakistan to, but Jinnah also intentionally installed his West Pakistani bureaucracy to be in full control of East Pakistan—-a province which they owed their nation’s founding to, but would prove to have no humanitarian regard for.

The groundwork for the economic exploitation, political disenfranchisement and internal colonization of East Pakistan began with the two years where Suhrawardy was banned from Pakistani politics.

After being unseated from Pakistan’s Constituent Assembly, he lived with his elder brother, Shahid Suhrawardy. Suhrawardy had publicly declared his plan to settle permanently in West Pakistan and on March 5, 1949 after Liaquat Ali Khan terminated Suhrawardy’s membership on February 26, 1949.

When asked what his brother was up to, Shahid would playful remark, “He is flitting like a fat turtle dove of peace between India and Pakistan.”

Indeed, Suhrawardy was restless in his endeavors, immediately wishing to continue his legal profession away from the halls of the Calcutta High Court, where his father served as a judge and he had been a trailblazer attorney. Unfortunately, the Courts of Karachi and Lahore were directed not to register him at the request of the Central government. Finally, a court in the small town of Montgomery enrolled Suhrawardy as a lawyer and he moved to Lahore, taking up residence in the house of Nawab Iftikhar Hussain of Mamdot.

Nawab Mamdot was an early advocate of the Muslim League as the only landowning family in Punjab that had pledged support for Jinnah from the start, while other Punjabi landowners opted for the Indian National Congress. Before Partition, Nawab Mamdot was President of the Muslim League in Pujab and when Pakistan was established, Nawab Mamdot was appointed the Chief Minister of Punjab. Shortly after appointment, he was removed from office and accused of misuse of power under the Public and Representative Offices Disqualification Act of 1949 (PARODA) ordinance.

Defending Nawab Mamdot was Suhrawardy’s first landmark legal case in Pakistan. While the defense proved to be oratorically and legally brilliant, Suhrawardy was not able to exonerate Mamdot completely. However, Suhrawardy removed the stigma that Mamdot had taken unwanted compensation, which was his first step towards building his name and reputation in a country he helped create. Suhrawardy’s most notable legal case would prove to be the Rawalpindi Conspiracy Trial, where the top generals of Pakistan were involved.

Pakistan’s First Opposition Party: The Awami League is Born

In the realm of politics and the restless pursuit for democracy, Suhrawardy issued the biggest favor for Pakistan through creating its first successful opposition party. As Suhrawardy recalls in his Memoirs, “After coming to West Pakistan, I decided to organize a political party to be called the Awami Muslim League, a suggestion I had already made to several of my friends.”

“After coming to West Pakistan, I decided to organize a political party to be called the Awami Muslim League, a suggestion I had already made to several of my friends.”

Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy in his Memoirs (1963) recollecting how he started the first successful opposition party in Pakistan.

Suhrawardy admits in his memoir that he “had been instrumental in creating and organizing the whole of Bengal and was known to the people as the architect of the Muslim League, but owing to differences in political outlook, I found myself in opposition to the Pakistani Muslim League (PML). The party that had united the Muslims in India to demand the creation of Pakistan, now developed into a closed corporation with blind support of the Central government with a fascist mentality.”

While Jinnah made the first mistake of installing inexperienced bureaucrats, his predecessor, Liaquat Ali Khan, put the nail in the coffin for Pakistan’s democracy through turning Pakistan into a one-party state.

Despite one of Jinnah’s very first speeches declaring that the Muslim League would be one of several political parties in Pakistan, Liaquat wished to preserve the PML as the only Muslim party. Liaquat, out of his own political vulnerability and greed, feared the prospect of a new constitution and a fresh general election which would bring into existence other Muslim political parties.

According to Suhrawardy, “In his [Liaquat Ali Khan’s] zeal for the Muslim League, he identified the party with the state and with the government, which was a Muslim League government, and maintained that anyone who opposed the Muslim League political party, and thus directly or indirectly his government, was a traitor to the state. This laid him [Liaquat] open to the charge of fascism.”

Fulfilling this daunting task of steering the first opposition party in a then-one-party state as a targeted politician, was generally more difficult in West Pakistan rather than East Pakistan. According to Suhrawardy, “In West Pakistan, the work was no doubt uphill, but it …had excluded a number of important and influential people from its membership, even detaining them without trial under the Public Safety Laws for daring to challenge the policies of the government. In East Pakistan, the Awami Muslim League found ready acceptance, for, after all, the Muslims of East Pakistan knew me very well; I had worked in Bengal for more than a generation and had spent twelve agonizing years among them in organizing the Muslim League.”

Clearly, Suhrawardy’s work was cut out for him in the Western wing, while the Eastern wing proved to be his base. Exercising the right to engage in free and fair elections was the only avenue for Suhrawardy and he undertook this endeavor within the new country he helped create headfirst.