By Mikail Khan

On Friday, December 12, 2025, a group of masked assailants gunned down 32-year-old Sharif Osman Hadi while he was in a rickshaw, firing from a moving motorcycle in the Puran Paltan area of the capital, Dhaka. The attack came just one day after authorities announced the date for Bangladesh’s first national election since the overthrow of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina. Shortly after, Hadi was flown to a hospital in Singapore for advanced medical treatment. However, he succumbed to his injuries and took his last breath on December 18.

Following the news of Hadi’s death, an enraged crowd vandalized the capital’s Chhayanaut Sangskriti Bhaban, a center dedicated to preserving Bengali culture. The offices of two prominent newspapers,The Daily Star and Prothom Alo were also set ablaze. These were institutions that embodied semblances of free thought, pluralism, and cultural multiplicity in Bangladesh. The incidents mirror the long-unfolding crisis that has gripped Bangladesh since its inception in 1971 to its post-July 2024 reconfiguration — the lack of accountability and complicity of Bangladeshi political leaders throughout a half-century in mitigating attacks on freedom of expression, particularly of its minorities.

Without addressing the breakdown in law and order, the interim government led by Dr. Muhammad Yunus, swiftly moved to declare that Hadi would be buried beside Bangladesh’s national poet, Kazi Nazrul Islam. The public agitation went so high that Hadi’s family members have demanded the inclusion of his biography in national textbooks and state recognition of him as a national hero. At the same time, a few people on the left questioned Hadi’s accomplishments and exactly what qualified him to be laid to rest beside the country’s most revered poet. It is important to note here that Hadi’s only poetry collection was “Lavay Lalshak Puber Akash” (“The Eastern Sky Turned Red Amaranth by Lava”) published under the pen name Shimanto Sharif.

Contrary to Western media associating Hadi to be a ‘key figure’ in Sheikh Hasina’s ousting, he did not, in reality, play a central role in the July 2024 uprising; rather, he emerged toward the end on August 5, once the prime minister was banished from the country. So, how then did Hadi become a focal figure in the uprising?

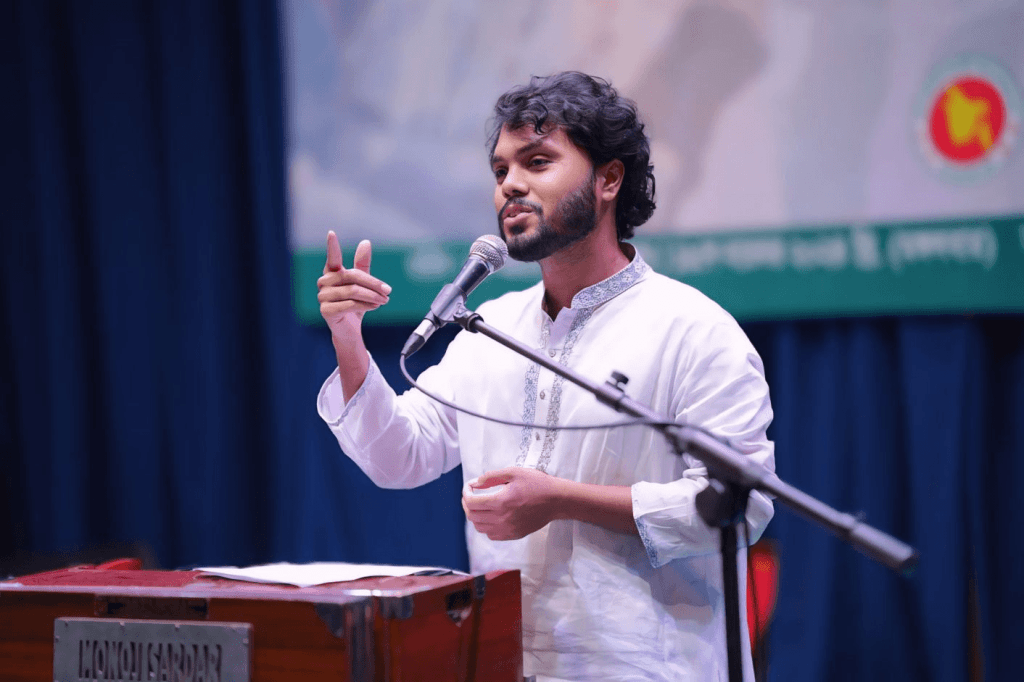

Hadi was a potential candidate for the Dhaka-8 constituency, formerly held by A.F.M. Bahauddin of the then-ruling Awami League. More notably, however, Hadi was also the convener of Inqilab Moncho, an organization that worked to oppose all forms of repression by allegedly drawing inspiration from political Islam and the latter’s concept of government and “fairness”. Shortly after the uprising, he rose to prominence due to his ability to emotionally appeal to a largely rural and non-urban citizenry with well-known “Bangladeshi Muslim” sentiments. His confrontational speeches circulated widely via social media as his politics espoused a virulent strain of Muslim ethnonationalism, a phenomenon that has been gaining rapid traction across Bangladesh. It is without a doubt that Hadi managed to captivate his impoverished audiences.

Bengali nationalism had already been pushed to the margins as a result of ‘Mujibism’ under Sheikh Hasina’s rule. The ousted Prime Minister enjoyed strong political backing from India, a perception that hardened after the 2019 and 2024 elections. Awami League critics and right-wing Islamist groups viewed New Delhi’s involvement as pivotal in upholding a regime that blatantly favoured India’s strategic, political, and economic agendas. The resentment toward Sheikh Hasina deepened the public’s desire for a new leader, who would not advance India’s strategic interests at Bangladesh’s behest.

Consequently, Hadi’s version of nationalism—one in which Muslims are portrayed as victims in their own land and their suffering blamed largely on an aggressive imperial neighbour, India—gained momentum. At a time when political Islamists with a lackluster sense of nationalism and Islamic right-wing forces seeking a caliphate by force were both clamoring for power, Hadi’s voice appeared comparatively restrained even to the most ardent leftist.

Since September 2024, Hadi has emerged as a populist and separatist public figure who mainly relied on anti-India rhetoric, anti-Awami League outbursts, and Islamic religious sentiments to appeal to the masses. Bangladeshi progressives have supported Hadi’s endeavors since then, some with moving tributes, even though the country’s Islamic Right has grown rapidly.

Inquilab Moncho’s gatherings were also often strategic rallies invoking the memory of those killed during the uprising while insisting that their deaths imposed unfinished obligations on the living. These tactics made him a somewhat perfect embodiment of the spirit of the July Uprising, even if he had not played a ‘key role’ in the uprising itself.

Yet, what are the limits of this progressivism when it comes to advocating for minority rights, particularly LGBT, non-Muslim, and Indigenous livability in Bangladesh? Can Bangladesh claim to have a truly principled left when its politics lionizes leaders such as Hadi, who has openly dehumanized trans and queer individuals?

On December 13, a day after Hadi’s assassination, তেলে-বেগুনে পোস্টিং (Teley-Begune Posting), an anti-LGBT Entertainment Facebook page, released a video of Hadi speaking about hijra, queer, and trans identities at a press conference. There, Hadi articulates his bioessentialist views on how Bangladesh must abide by three biological sexes: man, woman, and hijra. The video was widely circulated by a prominent anti-LGBT academic, Md. Sorowar Hossain, whose caption reads ‘Was the July Movement used to establish LGBT friendliness in the country?’

Bioessentialism is the ideology harbored by anti-trans proponents where an individual’s gender is fixed at birth and determined solely by unalterable biological factors. Numerous factions of Bangladesh’s society, ranging from the interim government’sReligious Affairs Advisor andmassive public protests against trans people’s existence, have similarly enumerated how Bangladesh must be purged of transgender individuals and subscribe to the three sexes previously mentioned.

While Hadi acknowledges hijra members’ participation in the July uprising, his references to the community and their futures in a post-July Bangladesh stop there. Rarely have students and political leaders expressed interest in furthering LGBTQ people’s lives in the new Bangladesh. Instead, various pro-July anti-LGBT student groups have mobilized on the streets to protest against transgender teachers from securing jobs in the educational sector.

Bangladesh media has also been complicit in the victimhood narrative of a hijra person as someone with no agency over their gender presentation and therefore, destined to an ill fate. These narrow understandings of a hijra person’s inability in self-determining their gender have become ingrained in the public imagination.

Subsequently, Hadi’s categorization of three fixed biological sexes serves the larger global clampdown on transgender rights where one’s sex assigned at birth and their gender identity carry the same meaning. Such disinformation campaigns have been refuted in medical sciences and some Bengali publications.

The video goes on to show Hadi’s conspiracy theories on how terms such as ‘tritityo lingo’ and ‘transgender’ are being leveraged to bring a ‘queer agenda’ into the country. Similar warnings against initiatives that harbor ‘homosexuality, transness, or LGBTQ’ agendas or their ‘mentally disturbed’ cultures have been issued by NCP leaders, Sarjis Alam and Hasnat Abdullah, as well as Islamist political party leader, Mamunul Haque.

This brings us to the night after Hadi’s death when three young men were harassed and cornered in Shahbag, one of the busiest intersections of Dhaka. A crowd gathered around the three youngsters who were accused of engaging in ‘moja’ (fun) homosexual behavior. Kalbela, an online news outlet, managed to interview one of the perpetrators, who manipulatively claimed that the decision to ask the group to leave the area was made out of concern for their safety, citing ‘fears’ that their presence could trigger mob violence. Hadi’s anti-queer rhetoric cannot be isolated from the way these young men were expelled from Shahbag’s premises.

The same period saw a litany of horrors open up for religious minorities as well, at the hands of Islamist-instigated mobs. On December 18, Dipu Chandra Das, a factory worker, was lynched and burned alive in Mymensingh after allegations of making derogatory remarks against Islam. The heinous crime was recorded on video with the mob chanting Allah’s name, demonstrating yet again that Bangladesh’s religious minorities, such as Hindus and Christians, do not belong in this ‘new Bangladesh.’ Later police investigations found no evidence that Dipu had said anything that he was accused of.

These occurrences have been shared to underscore the strategic alliances that have developed over time between NCP, Jamaat-e-Islami, and, consequently, the Inquilab Moncho platform, groups which have normalized Islamic right-wing presence in Bangladesh. Hadi’s death came at a time when we are seeing an influx of young Bangladeshis about to cast their first electoral votes, where his death is strategically being used to deepen their commitment to an Islamic Right rule of law and order. The assimilation has triggered a horrific acceleration of religiously fueled crackdowns, particularly upon LGBTQ individuals.

The very same factions that were built to alleviate Awami League-induced oppression are now perpetuating even greater atrocities on those with the least resources. When Dr. Yunus became the Chief Advisor of the newly formed interim government, minorities had hoped that he would usher in a new wave of democracy for the people of Bangladesh. As time progressed, it became clear that exacting revenge against his long-time nemesis, Sheikh Hasina, was more pressing than bringing in reform or anti-corruption measures. The interim government’s inaction on minority attacks has indicated a gradual accommodation of Islamist forces and a dangerous pattern of governance that Dr. Yunus had previously condemned when the Awami League held power.

At this stage, Bangladeshi minorities are battling for the soul of a nation, whose constitution was built on equality and non-discrimination. A new direction of thinking and mobilization for Bangladesh and its diasporic left would demand a closer scrutiny of the realities of everyday minorities – of legal processes that displace and remove certain communities from public life. The Bangladesh that is now teetering under the influence of right-wing Islamist parties needs to be overthrown by sharpening our political clarity and building defined leadership structures. Otherwise, we will continue to risk the plurality upon which Bangladesh was conceived, where violence and religious semantics will hold the course of justice hostage for generations to come.