By Sanaa Bashar

In the early years of Pakistan, language was more than a tool of communication; it was a battleground for defining national identity. The Bengali Language Movement, sparked by the imposition of Urdu as the sole national language on the people of East Pakistan (present-day Bangladesh) by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, is often remembered as the unifying struggle and symbol of Bengali cultural pride that transcended religious and political divisions. However, this popular narrative oversimplifies the complex dynamics within the movement.

The struggle for linguistic rights was not just about language but also about defining the relationship between Bengali culture, religion and national belonging. Bengali intellectuals, poets and cultural figures played a pivotal role in shaping this narrative, using their work to challenge the state’s imposition of Urdu and advocate for a Bengali identity that was rooted in both language and cultural history.

These intellectuals, however, were not united in their vision. Some supported a secular, inclusive Bengali nationalism, while others argued for a vision more aligned with Islamic identity in East Pakistan. This reflects how the movement revealed contested visions of Bengali nationalism, with intellectuals at the forefront, each articulating their own version of what it meant to be Bengali in Pakistan. Drawing on a variety of primary sources, including oral histories from key intellectual figures like Anisuzzaman, Badruddin Umar, and others, this essay argues that the Bengali Language Movement was not a singular, monolithic cultural struggle. Rather, it was shaped by deep ideological divisions, particularly between secular Bengali nationalists and those advocating for a Muslim-centered vision of identity within Pakistan. These tensions reveal that Bengali nationalism was an evolving vision. One that was defined as much by its internal divisions as by its opposition to the state’s linguistic policies.

Far before the Bengali Language Movement began in 1952, there were differing opinions on what the essence of Bengali identity was. As early as the eighteenth century, a new genre of Bangla was known as Musalmani Bangla. This form of Bangla drew heavily from Arabic, Persian, and Hindustani roots and began to flourish, primarily among Bengali Muslims. Meanwhile, with the influence of colonial-era missionaries, Orientalists, and Hindu Pandits, a newly Sanskritized form of modern Bengali was also being developed, with standardized grammar and traceable roots.

This contemporary Bangla became widely adopted in official educational and governmental settings and was soon regarded as the “proper” form of the language compared to Musalmani Bangla. Over time, most Perso-Arabic elements were stripped from this new “standardized” Bangla by its early creators and Bengali Hindu writers trained in the vernacular education system. This Sanskritized standardization, along with later prose works by well-known Bengali authors like Rabindranath Tagore and Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, reshaped the Bengali language into a distinctly Hindu cultural-linguistic style, moving away from its earlier Perso-Arabic influences. Gradually, Sanskrit-derived words were embraced as proper Bengali, and Sanskrit was idolized as the mother of the language. These linguistic divides would not remain confined to grammar or vocabulary alone; they soon found powerful expression in Bengali literature and poetry.

These early divisions in the Bengali language were mirrored in the works of prominent poets and intellectuals, who profoundly shaped the cultural landscape of Bengal in the decades leading up to the creation of Pakistan. Renowned figures like Rabindranath Tagore and Kazi Nazrul Islam became known for their secular—and at times Hindu-influenced-–visions of Bengali culture. In contrast, intellectuals such as Ghulam Mostafa took a more explicitly Islamic approach. They infused their works with religious themes and pushed back against the secular ideals promoted by figures like Tagore and Nazrul. As Bengal moved toward the creation of Pakistan, these divisions over language and culture would resurface in new ways, shaping the debates over national identity that soon emerged.

Following the partition of India and Pakistan in 1948, a national language had to be decided for the newly formed nation-state of Pakistan. The founder, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, declared that Urdu would be the sole national language of Pakistan. This decision shocked many Bengalis living in Pakistan, as they were not only a substantial ethnic group within the country but also had played a pivotal role in the creation of Pakistan. Jinnah himself had even acknowledged this in his first speech in Dhaka, stating that “East Bengal is the most important component of Pakistan, inhabited as it is by the largest single bloc of Muslims in the world.” Despite this recognition, Jinnah was adamant that Bangla could not be an additional national language of Pakistan due to its “Hindu overtones” and the belief that he and Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan shared that Urdu is “a language that, more than any other provincial tongue, reflects the finest elements of Islamic culture and Muslim tradition, and most closely resembles the languages spoken in other Islamic nations.” Therefore, Jinnah believed it was in Pakistan’s best interests to maintain Urdu as the sole national language, as it would unify both wings of the country and align with the Islamic-centered vision of the new state.

This decision, however, sparked widespread resentment among the Bengali-speaking population in Pakistan, who didn’t feel represented in a country they largely helped form. Urdu and non-Bengali Muslim culture replaced the dominance once held by high-caste Bengali Hindus and their Sanskritized Bengali, weathering the Bengali language down to a privatized, provincial status.

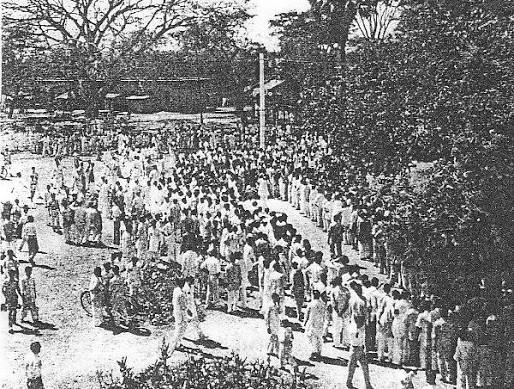

Jinnah’s emphasis on a singular language effectively homogenized Bengalis under the guise of nation-building. This discontent soon turned violent as Bengali students and intellectuals began protesting for Bangla to become recognized as one of the state languages of Pakistan. These protests were met with increased resistance from the government, with leaders like Jinnah labeling advocates for Bangla as “foreign elements” seeking to destabilize the nation. Furthermore, Bengali suppression went beyond language and was later reflected institutionally through the imposition of the 1955 One Unit Scheme, which effectively merged all of West Pakistan’s provinces into one unit while keeping East Pakistan separate. Although East Pakistan consisted of about 55 percent of the population, the scheme treated both wings as equal units, further diluting Bengali influence in national politics and increasing tensions between the state and Bengalis.

Despite these challenges, those advocating for Bangla to become a state language were not rejecting the nation of Pakistan. In reality, they were attempting to preserve the original spirit of the nation as they understood it from the 1940 Lahore Resolution, which had promised greater autonomy for the regions that would eventually form Pakistan.

The Bengali Language Movement brought together numerous Bengali intellectuals, poets, academics, and activists to fight for the recognition and inclusion of their mother tongue. However, this solidarity masked internal divisions that complicated the meaning of Bengali identity, particularly within the context of the new nation-state of Pakistan. Competing visions of what it meant to be Bengali were reflected in literature, political discourse, and cultural movements. Some intellectuals envisioned a secular, inclusive Bengali nationalism with no distinction between culture and religion. In contrast, others advocated for an identity closely tied to Islamic traditions and solidarity with the broader Muslim world.

Figures like Anisuzzaman, a prominent leader during the Bengali Language Movement, had a secular approach to Bengali nationalism that included both Bengali Hindus and Muslims. Anisuzzaman drew inspiration from Bengali poets such as Rabindranath Tagore and Kazi Nazrul Islam, whose works, while influenced by Hindu cultural traditions, maintained a broadly nonsectarian approach. However, not all intellectuals agreed with this secular approach to Bengali identity.

Jinnah himself had even acknowledged this in his first speech in Dhaka, stating that “East Bengal is the most important component of Pakistan, inhabited as it is by the largest single bloc of Muslims in the world.” Despite this recognition, Jinnah was adamant that Bangla could not be an additional national language of Pakistan due to its “Hindu overtones” and the belief that he and Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan shared that Urdu is “a language that, more than any other provincial tongue, reflects the finest elements of Islamic culture and Muslim tradition, and most closely resembles the

languages spoken in other Islamic nations.”

During the early 1950s, debates among Bengali intellectuals over the future of Bengali identity grew increasingly intense. Some Bengali intellectuals took a more Islamist approach, which at this time in East Pakistan meant advocating for a Bengali identity rooted primarily in Islamic traditions. Well-known Islamist-leaning intellectuals such as Golam Mostafa even went as far as calling for the banning of works by Kazi Nazrul Islam due to his references to Hindu deities. Likewise, politicians like Khwaja Shahabuddin shared similar sentiments, urging the Pakistani Parliament to gradually remove Tagore’s songs from radio and TV broadcasts, claiming they conflicted with the ideals of the newly established Pakistani state. Anisuzzaman and many other secular Bengali intellectuals viewed these efforts as a direct attack on Bengali cultural heritage. In response, Anisuzzaman organized a protest by gathering the signatures of 19 prominent intellectuals, an act that highlighted the growing divisions among East Bengali cultural figures over how Bengali culture should be defined.

Meanwhile, scholars like Muhammad Shahidullah attempted to chart a middle ground. Aware of the dangers of religious division, Shahidullah advocated for a modern Bengali Muslim literature to be written that could represent Bengali Muslim identity while remaining committed to universal human truths. He believed Bengali Muslims should develop a modern religious literature in Bengali, similar to the literary tradition built by Urdu speakers, without weakening ties to broader Bengali cultural heritage. In his view, literature’s greatness is in its ability to surpass communal divisions, allowing everyone to understand and enjoy it. He believed that creating a distinct East Bengali Muslim literary culture was important in the newly formed East Pakistan. While he recognized that much of the existing Bengali prose was heavily influenced by Hindu traditions, he did not view this as harmful; instead, he saw it as an opportunity for Bengali Muslims to learn from and expand their own literary representation.

Similarly, Badruddin Umar offers a unique perspective on the relationship between religion and language in Bengali nationalism. As a Marxist-Leninist theorist and a prominent political figure, Umar initially aligned with the Islamic identity of the Bengali Language Movement, although his views evolved. His early involvement with Tamaddun Majlish, an Islamic cultural group, highlights the different ways religion was tied to ideas of Bengali identity. The Tamaddun Majlis sought to promote Bengali as the language of the Muslim community in East Pakistan while still maintaining an Islamic ethos, which was an opposing ideology to the more secular leanings of intellectuals like Anisuzzaman. In his interviews, Umar reflected on his early hesitation toward the secular direction of the Language Movement. Although he was a supporter of the movement itself, he expressed concern about the movement being overtaken by secularists, who he feared might marginalize the Islamic contributions to Bengali culture. Umar emphasized that, in his view, Islam was not inherently opposed to the Language Movement; however, he was deeply wary of the movement’s potential to be taken over by secular nationalists.

Unlike Shahidullah, who advocated for a modern Bengali Muslim literature that bridged both Islamic and broader Bengali cultural traditions, Umar’s stance was more rooted in the idea that Bengali identity could be shaped through an Islamic lens without compromising the political and social aims of the Bengali Language Movement. While both intellectuals agreed on the importance of Muslim identity within the movement, Umar emphasized the need to preserve Islamic values, whereas Shahidullah focused on creating a literary tradition that could transcend religious divides. This contrast highlights the wide range of ideological positions surrounding Bengali identity in East Pakistan, from secular nationalism to Islamic cultural preservation, showcasing the complexity of the movement in its early stages.

As debates over the cultural and religious dimensions of Bengali identity unfolded, political parties began to emerge, each offering its own vision for how language, religion, and nationalism should shape the future of East Pakistan. The majority of these newly formed political parties shared the common goal of making Bangla an official state language in Pakistan, but differed significantly on strategy, ideology, and overall vision for the new state. The East Pakistan Youth League (Juba League) was a significant organization, initially non-political and non-communal, but later became of great importance during the Language Movement in 1952. Bengali academic and activist Anisuzzaman was among those associated with the Juba League, which he stated drew much of its early leadership and momentum from individuals connected to the Communist Party.

Despite the Communist Party being a main force in the Youth League, the parties held different stances on critical tactical decisions. A major point of contention among the organizations was whether or not to violate Section 144. Section 144 was a colonial-era law still in effect under Pakistani rule, which allowed authorities to prohibit public gatherings of more than a few people in a given area in order to prevent “unlawful assembly” and maintain public order. Violating Section 144 would mean directly challenging state authority and protesting in public for Bangla to become an official state language while risking violent repression. The East Pakistan Youth League was very much in favor of violating 144, with its leader, Oli Ahad, voting for it. However, the Communist Party itself was not in favor of violating Section 144, fearing it would be seen as an “adventure” and give the government an excuse to delay the general elections that hadn’t been conducted in the last five years. This concern about preserving the chance for elections represented a “constitutional approach.”

In contrast, those favoring violation felt that not fighting against unfair laws would allow the government to continue imposing unjust laws on them, adopting a more “populist” approach. Additionally, other political parties, such as the Awami League — a major opposition party formed by former Muslim League members to represent Bengali interests; and the Student League, its affiliated student wing, were also reportedly against breaking Section 144.

Beyond strategy, these groups also differed on ideological and cultural grounds, particularly regarding the shape of the Pakistani polity and acceptable cultural traditions. Groups like the Pakistan Sahitya Sangsad (Pakistan Literary Society), a left-oriented literary organization, explicitly opposed organizations like Tamaddun Majlish, viewing them as Islamists. While both groups favored the Bangla language, they differed significantly on what literary tradition to embrace; the Pakistan Sahitya Sangsad advocated for accepting the entire Bengali cultural tradition as a whole, without division, opposing views that suggested banning works with references to Hindu gods. They also advocated for a secular polity and prioritizing local tradition over Islamic tradition, contrasting with the Islamist perspective they attributed to Tamaddun Majlish. The debate between these secular and Islamist cultural backgrounds was actively maturing. Political parties began to increasingly divide, reflecting the range of ideological views on Bengali identity, transforming into social activism. Overall, while united by the language cause, these organizations represented diverse political strategies and competing visions for the cultural and political future of East Pakistan within the larger Pakistani state.

Although the Bengali Language Movement involved a wide array of political, social, and intellectual groups advocating for the recognition of Bangla as an official language of Pakistan, it was far from a unified effort. The movement consisted of complex, competing ideas, each layer reflecting different visions of what it meant to be Bengali within the newly formed state of Pakistan. Long before the movement gained momentum, debates over Bengali identity had already begun, rooted in the diverse ideological and cultural history of the Bengal region. These debates were shaped by a

mix of factors, including regional political struggles, the religious divide between Muslim and Hindu Bengalis, and the rise of secular and Islamist factions. This created the grounds for ideological disagreements over the role of language in defining the Bengali self. The struggle for inclusion was therefore far from linear. It was characterized by deep ideological division, with no one party arriving at a fixed concept of Bengali identity or its place in the broader Pakistani state. Muslim Bengalis, secular Bengalis, Hindu Bengalis, and Islamist Bengalis each differed on how the Bengali language was to be maintained, what scripts were to be employed, and how literature and intellectual life were to play a role in the construction of Bengali identity. These differences weren’t just limited to what was written; they were also reflected in the everyday social and cultural life of Bengal.

The tensions around Bengali identity during the Language Movement were not just about language but about deeper struggles over culture, religion, and power. Within the Bengali community, there were major divisions over what Bengali identity should look like: some intellectuals focused on preserving the region’s rich literary tradition, which drew from both Hindu and Muslim contributions, while others emphasized a more Islamic cultural identity. Meanwhile, the Pakistani state aggressively pushed Urdu as the sole national language, framing it as a unifying Islamic language and portraying Bengali as less legitimate because of its Hindu and secular roots. This excluded not only Bengalis but also other minority groups within Pakistan who did not identify with Urdu. The presence of various writers and thinkers, each with differing ideas about Bengali identity, made it even harder to present a unified front. These internal divisions, alongside the state’s insistence on subordinating Bengali to Urdu, ultimately shaped

how Bengali identity evolved under Pakistan and deepened the exclusion of Bengalis from the national project. Yet, despite their differences, most Bengalis involved in the movement were ultimately united in rejecting Pakistan’s attempt to silence them — each group simply wanted the state to reflect their vision of what Pakistan was supposed to be.

Therefore, fundamentally the Bengali Language Movement was not just a fight for language preservation but a larger fight over who determined the terms of Bengali culture, history, and identity within a new nation-state. The movement reveals how language, power, and competing visions of identity were tightly linked in the struggle to define cultural and national belonging.

The complexities of Bengali identity and nationalism were not just confined to the Bengali Language Movement, but can be seen reflected in the aftermath of the July Student uprisings, which saw the ousting of former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, an Awami League-linked longtime figurehead. International media coverage of the uprising often framed the events that took place in vague, surface-level terms without placing the movement in context of the wider history of Bengali nationalism . In many news outlets outside of Bangladesh, the movement was portrayed as a straightforward conflict between the Awami League and Islamist Forces. Sohul Ahmed, a researcher on Bangladeshi history and politics, notes that prominent analysts and many Indian media sources have framed the uprising as either led by or favored by Islamist groups. This framing substantially oversimplifies the nature of the uprising and minimizes the contributions and presence of other political parties and social actors, mirroring the same reductive tendencies that have historically framed the Bengali Language movement as a homogenous struggle, as opposed to competing ideologies and divisions.

The activist, Farhad Mazhar, a key figure in the July Movement, challenges these reductive narratives, emphasizing that the struggle over identity in Bangladesh is not a binary of “Awami League versus Islamists.” Mazhar argues that the country is grappling with two forms of authoritarianism, “secular facism and religious nationalism.” In the context of religious nationalism, he warns against the wrongful use of Islam as justification for authoritarian objectives, while at the same time advocating for the recognition of Islam’s historical and cultural role in shaping Bengali identity as essential to understanding the contemporary political moment. In this way, Mazhar’s perspective resists the expulsion of Islam from Bangladesh’s history, but condemns its exploitation for political gain. This perception parallels earlier internal divisions that occurred during the Bengali Language Movement, where intellectuals like Muhammed Shahidullah and Badruddin Umar navigated the tensions between Muslim identity and broader Bengali heritage. Ultimately, the debates over Bengali identity that emerged during the Bengali Language Movement have persisted into the present, as seen in the July uprising, showcasing that the nation’s identity continues to be contested across multiple social, political, and religious lines.