Interview with Fahim Hamid, Director of “Bengal Memory”

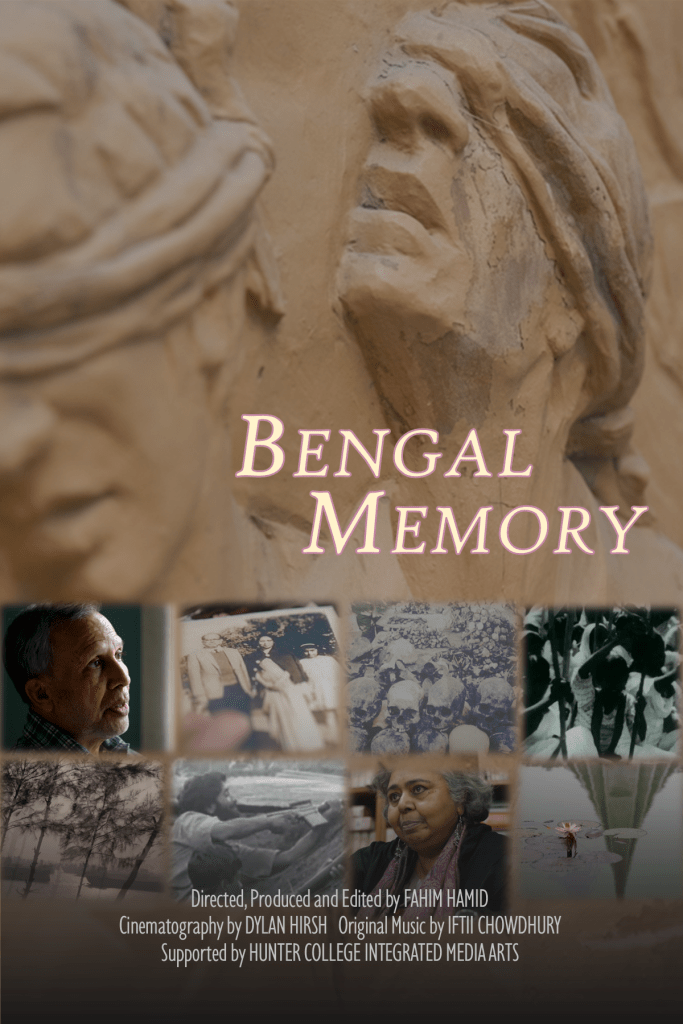

As part of the first-ever Bengali Film Festival held in New York during the summer of 2024, NYC-based filmmaker Fahim Hamid screened his documentary “Bengal Memory.” Originally, his 34-minute documentary was a grad school thesis where he wanted to showcase the story of how the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War affected his own family and how its legacy carries on with him to this day. The goal of “Bengal Memory” is to give the genocide and liberation war the treatment that many other independence movements have received: an exposure to a mainstream Western audience where much of the diaspora exists but knows little of its ancestral history. Fahim narrates the history of the independence of Bangladesh with a special eye towards the U.S. role in facilitating the genocide, while incorporating the perspectives of his own family, liberation war survivors, renowned writers, museum curators and many others.

L.A.-based Bengal Gazette Editor, Rimon Tanvir Hossain, had the pleasure of speaking with Fahim before his next film screening at the Center for Asian American Media (CAAM) Festival on Sunday, May 11 at AMC Kabuki 11 in San Francisco, California. This article captures that conversation and its many takeaways, as Fahim’s “Bengal Memory,” is perhaps one of the first documentaries of the Liberation War by a Bangladeshi-American aimed towards making its legacy more digestible for the many Bengalis in the diaspora today and for non-South Asian folks.

Interview Questions

- Q: What compelled you to make a film on the legacy of the 1971 Liberation War? Anything related to your career as a filmmaker or a personal desire to be more in touch & informed with your history?

- As someone born in Chittagong, I obviously had a personal connection to Bangladesh and its history. But I grew up in the U.S. after immigrating here when I was a child and knew very little details about the war–it’s only something I came to learn later, gradually, through my family’s sharing of their experiences with me. And then, as an American, I grew up in a post-9/11-wartime era where I became very curious and critical about the U.S. government’s imperial footprint abroad. These two aspects of me are the confluence of the film, essentially. In college, I studied film & theater, planning to be an actor, but I always yearned for creative liberty to do something on my own family and country’s story. I read Gary Bass’s The Blood Telegram a few years after graduating, which gave me a good political perspective and broader historical perspective on top of that which I learned from my family. Putting both the personal and political together, this gave me the feel of a cinematic narrative evolving, and I knew this was intune with a decolonial narrative that was developing in my generation. Among the people I wanted to interview was Salil Tripathi, author of the Colonel Who Would not Repent, who lived in Mumbai during the time of the 1971 War and continues to be a renowned journalist on Bangladesh and a resource for me. The thing that began to emerge for me was that the 1971 war may have seemed to many people then and now as an isolated regional conflict, but in reality it was a part of a bigger narrative during that Cold War era and the plight of the Global South. With the Vietnam War and covert and overt interventions by Western powers all over the world at that time, the events in Bangladesh were yet another episode of a colonial legacy being defied. I knew that this story could appeal to a larger audience today. I noticed that much of what we learn as Bangladeshi-Americans or Bengalis globally was not touched upon in the U.S. media system and my own anti-war activism put me on a quest for a different perspective. I attest a lot of my drive in doing this documentary and highlighting the importance of storytelling on the 1971 Liberation War to conversations with my father and family stories. As we see in the documentary, my father lost someone during the war, who was hiding in a building from machine gun fire. It gave me the realization that the comfy life I live right now could have been erased.

- Q: You incorporate conversations with your father and pictures of your home in New York and juxtapose it with scenes and footage from 1971. Why did you feel this carries more weight to folks who may feel disconnected or unconcerned with how these events affect them? Any motives behind this?

- I wanted the audience to reflect on my journey and the journey of Bangladeshis at large, especially if they’re part of the diaspora like me. We can see the events if we search on Wikipedia, but to really get to the truth of it, we must discover our stories. For me, there was a giant gap between my father growing up in Chittagong in the 1960s to arriving in New York in the 90s. Many Bangladeshi-Americans might be familiar with that–a piece of their parents’ story that seems missing and they only learn later. I feel like this perspective on storytelling has more resonance for the Bengali diaspora, more than the well-known and accessible documentaries filmed by BBC or other Western outlets, Indian outlets or even Bangladeshi outlets. Today, some of us in the diaspora are one to two generations removed, but how do we make sure that these stories live on and people pay attention to them? There was this interesting New York Times article about a NYC cab driver, who was once a Mukti (Bangladesh Liberation War Freedom Fighter) and went on to be a politician and a businessman, but now lives a relatively mundane life as a cab driver. I think another motive was for people to know that 1971 was not just a single flashpoint, but a similar recurring cycle with parallels to Sudan and Palestine. It’s your history and you are a part of that.

- I feel like my documentary is meant to serve as a remedy to make people care. As we witness our generation and successive generations get older, we worry we might lose these stories, these memories. There are many famous films that capture similar conflicts in history: WWII, Vietnam, Korea, etc. And I thought the story of Bangladesh’s liberation is indeed a very grand story, and it made me wonder: why can’t it get a “Hollywood”-treatment of sorts someday?

- As for logistics in filming the documentary, this film was part of a graduate school thesis, which I am planning to make into a bigger feature. My colleague from grad school, Dylan Hirsh, was the cinematographer for some of the New York shoots. We didn’t have much of a budget, so our approach was a very simple, conventional documentary approach and we obviously relied on a lot of archival material. We used Panasonic Lumix cameras during the New York shoots. In Dhaka, at the Bangladesh Liberation War Museum, where we interviewed Mofidul Hoque–a well-known historian and founding trustee of the museum–I actually had access to a full-on studio with equipment and crew. Fortunately, I also had a family relative there, Riaz Ahsan, who is a military guy and history buff, and he helped as a production consultant throughout my time in Bangladesh for filming this documentary.

- Q: Many Western & Indian documentaries are well known and easily accessible to watch and learn about this history. How do you feel your documentary disrupts this and makes the history more digestible for Bangladeshi-Americans and those without a personal connection to 1971? How can we make more progress in informing future generations?

- There are many angles to looking at the 1971 Liberation War and it often works under an agenda based on who’s telling the story. We get more cognizant of this as we learn from other perspectives and I personally had to toe a line in many narratives, where I feel that I fell somewhere in between. What everyone frames is never easy terrain, even within my own family. In the West, the post-war story of the U.S. government’s involvement and the liberation movement is one of triumph for the Bangladeshis and failure/moral bankruptcy on part of the Republican Nixon administration, where his National Security Advisor, Henry Kissinger, had a huge hand. For India, they acknowledge 1971 as “Bijoy Diwas,” a total victory over the Pakistan Army, where they portray themselves as saviors of Bangladesh and protectors against Pakistan. Obviously, these are battling narratives based on vested interests as the Pakistani narrative sees 1971 as a third showdown with India, where they were merely reacting to India’s grand designs to replace East Pakistan with an Indian-friendly government. I am also invested in informing a non-South Asian audience on the 1971 Liberation War that captures all the information, without having a vested interest on nationalism, Partition and subjectivity on my end. Quite the daunting task!

- Q: Your documentary does a good job of narrating the buildup to 1971 and emphasizing the plight of women and minorities in Bangladesh. What difficulty did you have in making sure these voices and narratives were well-accounted for and different from the more nationalist retellings that are often contested due to political agendas?

- I observed how nationalism can be empowering, but also very dangerous–it can be a liberating movement, such as in 1971 against an occupying force, and on the other hand, with the fascism we’ve seen in the past and today, it can be destructive. And there can be a fine line between the two. On the topic of women and minorities, we conventionally view women as victims during the war. Salil’s harrowing accounts show how even as Bengali women were getting raped by Pakistani soldiers, they were asked whether they were “Bengali or Muslim,” to which they responded to with, “both.” The story of women victims of sexual violence is a major one in its own right, that I was not able to cover in the limitations of my short film. However, in the 1971 Liberation War, we also have very memorable images of women marching with rifles as Freedom Fighters in the street. I have an unused interview with a woman freedom fighter, but decided not to include it due to the time constraints of this iteration of the film. The topic of religious and ethnolinguistic minorities is a constant in Bangladeshi and wider South Asian history, politics and discourse due to how it relates to political rhetoric and nationalism in each state. I believe the religious diversity in Bangladesh is comparatively significant–for example, if we look at demographics in the U.S., the next biggest minority religion after Christianity is just 2.5% Jewish people, and then Muslims at 1%. However, in Bangladesh, India and Pakistan, the religious minorities are 7.95%, 14.2% and 2.1%, which shows how much more religious coexistence is a palpable aspect of society on the subcontinent.

- Q: Halfway through the documentary, you shift from looking at developments leading up to and during 1971 to how your current country played a role. There’s a lot of archives and recordings that many writers, scholars and other people have also used over time. How did you make sure your analysis was different? You made a point to talk about Iran & Jordan’s connection. Why the emphasis here?

- When we switch the focus, halfway through the documentary on the stance that my current country—the U.S.—played, we notice that Nixon and Kissinger funneled weapons illegally in order to sustain Pakistan’s genocide in Bangladesh. Their middleman in the operation was the Shah of Iran and the King of Jordan, who helped facilitate the arms transfers during the war as the U.S. were in the midst of their opening to China, which Pakistan served as a backchannel for. The point of curiosity here is that this plot is part of a larger narrative of the U.S. given that Shah Pahlavi in Iran was a puppet government and U.S.-friendly regime which came to power due to a well-known CIA coup that replaced democratically elected Mohammed Mosadegh, whose plan to nationalize Iran’s oil, threatened Western interests. On one level, they were “Muslim brothers,” seeking to help each other out, but also there was a wider U.S. plan to divide-and-conquer, by putting groups against each other. Although, I don’t believe this was the motive by Nixon and Kissinger in choosing Iran and Jordan–it was most likely that it was logistically the most obvious route for them to funnel weapons. The whole affair is extremely similar to what happened in the Iran-Contra scandal a decade later with Reagan. Mujib, once in power in independent Bangladesh, once quipped that after the assassination of Salvador Allende in Chile (in a C.I.A.-backed coup), “I’m next.” Bangladesh was essentially a casualty of the Cold War, and Iran and Jordan were wrapped up in it. I think the Bangladeshi voice is important in delving into this unique history, given the desire and motivation to understand our present condition through tracing the steps of our people’s history.

- Q: One criticism I have is that you mentioned very little about the Indian role in 1971 and focused more on Pakistan and the U.S. Was there a reason behind this and not mentioning the Soviet and Indian hand in 1971?

- I feel like tying in Indo-Soviet cooperation in the Bay of Bengal and the wider South Asian context within the 34 minutes was difficult. You’re right that 1971 was a U.S. pin to the coffin on the Sino-Soviet split as the Nixon to China pivot did happen on Pakistan’s watch, which gave them cover for their genocide. At the same time, due to India’s embrace of Non-Alignment and socialism, the U.S. treated India as a Communist-sympatico. I argue that Soviet involvement in 1971 was very reactionary, by making sure that India was not in the U.S. camp and Bangladesh was essentially a background character here. This was clear to me when the Soviets sent a fleet to intercept the U.S. 7th Fleet’s advance into the Bay of Bengal. I think there’s space to talk more about the Indo-Soviet hand in 1971 when I turn this documentary into a full feature.

- Q: To future documentary filmmakers & writers hoping to shed more light on 1971, what advice do you have? Your film did a remarkable job of incorporating everyday folks, your family, museum curators and renowned writers like Salil Tripathi. How can we make sure the next and current generation of writers, filmmakers and storytellers are moving the ball forward? You employ your own anti-war activism and insights from the current climate on Palestine. How do you feel like this affects retellings of 1971?

- I think the future generations should think about the audience first and foremost. Whether it’s a room of Bangladeshis, Indians, Pakistanis, non-South Asians,think about who you want to reach and your conviction. What’s the objective in telling the story? Now that we established that the 1971 Liberation War is so grand with the Indians & Soviets trying to oust Pakistan and its American backers, why don’t we turn this into a grand film with a full-on Hollywood treatment like movies on the Vietnam War?

- Think about your message and remember that there is no singular narrative. Aim to find the truth and focus on what matters to you. Do not shy away from what counts but be sure to do your research. Let your own voice and perspective guide the story, because there is no such thing as objectivity here.

- My own anti-war activism is evident in the documentary. I worked in political campaigns in the U.S. and my transparency about my subjectivity is intentional, I believe there is always subjectivity in creating any art. That is also juxtaposed by the transparency of my research, sources and their credibility to convey the facts of the events in the film.

- I first screened this film in grad school then at the CUNY Asian American Film Festival and I am happy to be featuring it next on the West Coast at the Center for Asian American Media (CAAM) Festival in San Francisco. I want to get a wide audience and take insights from what my viewers think.

- Q: Given how the ouster of Sheikh Hasina in August 2024 has changed the narrative on liberation in 1971, do you feel like capturing the legacy of 1971 as a liberation war has changed or become more difficult. In what ways do you feel so, if you agree that it has?

- What is happening now with the recent fall of Sheikh Hasina and its aftermath seems to be part of an ongoing cycle from the last 50 years in Bangladesh where corruption, martial law, rigged elections, assassinations, etc. went back and forth between various political parties. From the assassination of Mujib, his reputation as the hero and voice of Bangladesh’s independence is the easiest and most well-known angle, but not without its heavy controversy in Bangladesh. The destruction of statues and the residence of Mujib is a major flashpoint here. Mujib and his Awami League succession under Hasina and other leaders historically pushed for a secular democratic vision for Bangladesh. What was striking–and this is something that many people, such as Salil Tripathi and Mofidul Hoque in the film have said–is that after Mujib is assassinated, a more Islamic-nationalist regime comes in and they change of the slogan of Bangladesh from “Joy Bangla” to “Bangladesh Zindabad”, an Urdu phrase–the language of their oppressors. I think there are many questions surrounding the assassination of Sheikh Mujib, and one of these is the question that was at the heart of the liberation itself: is Bangladesh a country of the Bengali people, or of Muslim people? I think that is still the question playing out today, in the aftermath of Hasina’s ousting as well. The protests themselves were against Hasina government’s quota issue, which were basically an abuse of the memory of 1971 to promote their own cronyism, which people now justifiably question after all the unrest between July and August 2024. Then there was violence that followed after the ousting, against religious minorities and a re-emergence of an Islamic nationalism–all of these are a repetition of a cycle that Bangladesh has seen many times since 1971. So I feel like the Yunus Interim Government’s rise to power now re-hashes the original question of what is a Bengali and what would an independent East Bengal homeland look like? The identity of the country is once again in turmoil and honestly with how current politics are playing, these questions are still open-ended with high cost to the civilian population.