By Monica Chowdhury

In July, when Bangladesh was boiling with rebellion, sparked by the Awami League government’s counterblow against the Quota Reform Movement; a photograph of a child took over social media. Riya Gope, a six-year-old, was shot in the head by the police while playing on the rooftop of her home in Narayanganj. Caught in a clash between the police and the local protesters, the child’s tragic death left her family and the nation devastated.

Riya Gope was one of the 32 children killed by the state-endorsed armed crackdown against the Quota demonstrators. According to the Human Rights Support Agency (HRSS), the bullets of law enforcers claimed approximately 875 lives and left over 30,000 injured between 16 July to 9 September. A peaceful movement advocating fair job opportunities for youth escalated to a nationwide ek dofa-ek dabi (one point, one demand movement), demanding Sheikh Hasina and her cabinet’s resignation. The increasing death toll added fuel to the fire. It finally forced the 77-year-old daughter of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman to step down and flee Bangladesh, seeking refuge in India. Awami League’s authoritarian rule of fifteen years had thus ended rather unceremoniously, as the president of the party went into a self-imposed exile.

Deprived of democratic rights for over a decade, public frustration had reached a boiling point. Moments after Sheikh Hasina’s ouster, years of injustice exploded in a carnival of outrage. On one side, people prayed in the streets, while others ransacked Gonobhaban (Bangladesh’s Prime Minister’s residence), which they viewed as the powerhouse of a ruthless regime. Three consecutive fraudulent elections ridiculed the idea of democracy, (Professor Dina Siddiqui coined the term- “tamasha” of Democracy) resulting in jubilant people pouring into the National Parliament Building in celebration. But, within a matter of hours; news, pictures, and videos of vandalised temples and idols emerged on social media with the hashtag “Save Bangladeshi Hindus”.

The initial wave of collective optimism was thrashed soon— as a surge of communal tension unfolded, testing the unity of people. The human toll of rebellion, the flood of misinformation breeding mistrust and the turning tides of international affairs currently pose growing challenges for the government four months into its interim tenure. About 173 million people living by the Bay of Bengal now navigate the turbulent waters to stay united, to build a strong Bangladesh after a bloodstained uprising.

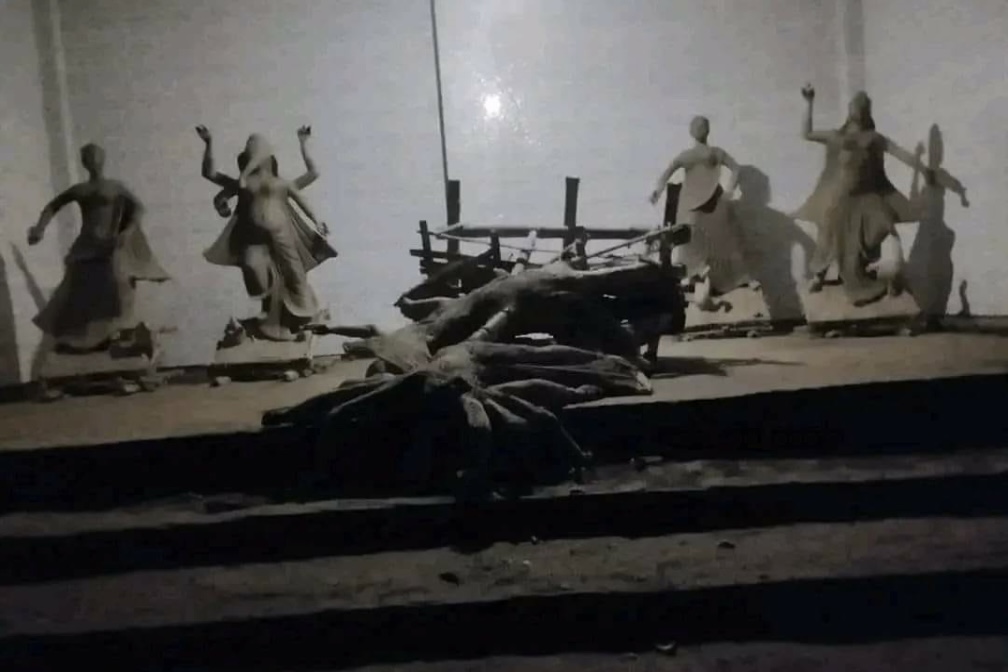

When Asha* received a call from her mother in Netrokona; a district located about 150 kilometres south of Dhaka–saying that some temples in the village had been attacked, and they remain fearful of more attacks; her heart sank. Asha, a Bangladeshi Hindu living in Japan, was a strong voice during the Quota Reform Movement. Her mother was unsure about who committed the crimes. From 5 to 20 August, a total of 1,068 houses, and business establishments had been attacked, looted, and vandalised, while two died according to a report published by Prothom Alo. Christian, Ahmadiyya Muslim communities, and members of the ethnic minority also faced attacks, as per the report. “It is hard to be rational when you are losing means of livelihood, and it is dehumanising,” commented Asha.

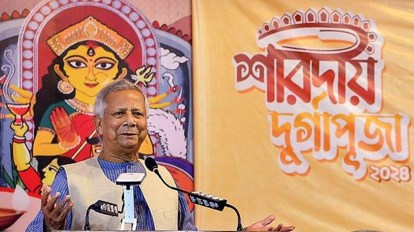

After three days of unrest and anticipation, on 8 August, the interim government was formed under the leadership of Nobel laureate and microfinance pioneer, Dr Mohammad Yunus. He urged the nation to remain patient. After taking oath as Chief Adviser of the Interim Government, he visited the Dhakeshwari Temple. “We are all one people with one right. Do not make any distinctions among us. Please assist us. Exercise patience,” said the Chief Adviser. Human rights groups, intellectuals, and sociocultural organisations also came forward to condemn the acts of violence against minorities. Amid the internal unrest and external escalation of the situation in the mass media, Bangladeshi youth condemned the violence with street art with slogans of communal harmony on the walls of educational institutions and public spaces. They formed volunteer groups to patrol non-Muslim institutions. Madrasa students guarding places of worship posed hope for Bangladeshis in times of trouble.

In protest of the attacks on minorities, protests organised by the “Hindu Jagaran Mancha” were held at the Shahbagh intersection. Hundreds of protestors from Hindu communities blocked the road and demanded greater minority protection. They issued an eight-point demand during the rally: seeking the government to pass a “Minority Protection Act,” establish a Ministry of Minority Affairs, and set up a tribunal for the prosecution of violence against minorities. Along with similar developments for Buddhist and Christian trusts, they also demanded that the Hindu Religious Welfare Trust be converted to a Hindu Foundation. They aimed to modernise the Sanskrit and Pali Education Board, establish worship areas in educational institutions, and properly implement the Vested Property Restitution Act. Finally, they called for a five-day Durga Puja holiday. The protestors vowed to continue the protests if measures were not taken against the persecution of Hindus. They chanted slogans for protection like: “Save the Hindus”, and “We will not leave Bangladesh”.

Dhaka University student Tithy* has received images of wrecked shops and damaged idols from her classmates living outside Dhaka. They voiced increasing fear of coming back to the university campus. “We supported the quota reform movement; every Hindu friend of mine expressed solidarity demanding an inclusive Bangladesh. And this is the result. Why are we being targeted? Why is it always us?” Tithy sighed. Concerns grew as incidents of miscreants vandalising Durga idols in several districts were recorded.

The betrayal faced by youth like Tithy was not uncommon for minorities, regardless of who was in power. Traditionally, the Hindu community, a population in decline, has leaned towards supporting the Awami League, a party that presents itself as a proponent of all religious and ethnic minorities. As Asha elaborated, “Currently in Bangladesh, there are no political alternatives other than BNP and Jamaat-e-Islami. For Bangladeshi Hindus, the Awami League is viewed as the lesser evil. Which is why they are preferred.” While the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) led coalition government has a poor history of protecting minorities– under the Awami rule, violence towards Hindus remained pervasive. In the last nine years as of 2021, a total of 3,710 attacks against the Hindu community took place, as land disputes and property seizures have pushed many Hindus to the brink of poverty.

In 2021, Rana Dasgupta, General Secretary of the Bangladesh Hindu Christian Buddhist Unity Council, called on the Awami League for “self-purification,” remarking, “When Awami League came to power, we thought there wouldn’t be any repetition of communal attacks, but contrary to our hopes, communal attacks have continued and increased.” Additionally, throughout the history of Bangladesh, minorities have borne the brunt of political upheavals. With most crimes going unpunished, the cycle of unrest continues.

After the fall of the Awami League, social media swelled with posts about the “persecution” of Hindus in Bangladesh. Digital campaigns conveyed that Bangladeshi Hindus were facing “genocide” and “mass rape” by “Islamists”. Elaborate reports by Prothom Alo, BBC, Netra News and AFP fact-checker Qadruddin Shishir debunked false, or fabricated cases, revealing that the attacks were politically motivated rather than communal. In a phone call with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Dr Yunus asked Indian journalists to pay field visits to get the real picture of what was happening in Bangladesh. The press secretary to the Chief Adviser Shafiqul Alam said, “They should see the situation themselves and do reports accordingly rather than being dictated by any secondary, and sometimes very exaggerated reports.”

For example, On 9 August, a video on X handle claimed that “Jihadists” had detonated bombs at a camp of Hindu women and children, killing hundreds. A fact check by Rumour Scanner revealed that the video was from a tragic incident on the 7th of July, where five people died from electrocution during Rath Yatra celebrations. Another report by BBC verifies that most of the social media handles spreading misinformation were geo-located in India. A viral post falsely claimed that a temple in Chittagong, Bangladesh was set on fire by “Islamists”. BBC confirmed that the Temple was undamaged. The fire occurred at a nearby Awami League office on 5 August. A temple staff member confirmed it was unaffected and was being guarded. The sensational cyber-attempt fell short–as misinformation nullified the true sufferings of the apolitical, common Hindu populace, leaving them more frightened and hopeless. Moreover, after the regime change in a country of nearly 150 million Muslims, the misleading media claims lacking coverage on the scale of the July crackdown, civilian deaths and the aspirations of Bangladeshi people – amplified mistrust within the people of the two countries. “This kind of misinformation treadmill needs to be stopped immediately lest it leads to further instances of violence, and makes the people-to-people divide between Bangladesh and India even worse,” commented Zillur Rahman, the executive director of the Centre for Governance Studies.

In recent years, these two diverse countries of the Indian subcontinent, connected by 54 shared rivers, and the world’s largest mangrove forest, have seen a rise in majoritarian communalism. People’s religious sentiments, day-to-day aspirations, fears, ambitions, and economic hierarchy are exploited to incite emotion for political gain. Meghmallar Bose, a Dhaka University student and the Bangladesh Student Union President said, “The crimes are premeditated, fuelling communal unrest would help the fallen regime and their foreign patrons to establish divisive narratives.” According to Ramon Magsaysay Award-winning Indian journalist Ravish Kumar, referenceless memes of “Whatsapp University” have replaced the evidence-based discourse of history. He addresses that majoritarian politics do not come with a name tag but, through rewriting history, slowly change our mindsets.

During this year’s Durga Puja celebrations – one of the biggest religious festivals of the Hindu community, Dr Yunus led the government to ensure security. While the interim government manoeuvred the multilayered issue of attacks on minorities; the 45th and soon-to-be 47th president of the United States, Donald Trump commented on the matter. On the eve of the U.S. general elections, Trump described the attacks on minorities as “barbaric” and that it would have “never happened on my watch”. Chief Adviser Yunus responded to the statement as “baseless propaganda”. He added that U.S.-Bangladesh ties “would not change drastically” on Trump’s win and congratulated him for the victory in retaking the White House. Previously when the longstanding democratic-party ally took office, the Biden-led U.S. government “offered continued support for Bangladesh’s new reform agenda”, and pledged $202 million of aid for economic growth.

Prior to the U.S. presidential election, Sheikh Hasina’s son, Sajib Wazed Joy, reportedly hired a lobbyist close to Trump’s administration who will “engage with the Executive and Legislative Branches of the U.S. government to provide insight on the issues facing Bangladesh”. While Sheikh Hasina and the top leaders of AL are on the way to being sued by the International Crime Tribunal for crimes against humanity – Trump’s win may have ripple effects in Bangladesh. Foreign Policy columnist Michael Kugelman speculates that, “Trump triumph could pose new challenges for a recently revitalised bilateral partnership.”

As the Hindu Jagran Mancha platform had been staging protests since August, the main speaker and spokesperson Chinmay Krishna Das Brahmachari implied they deserved seats in the parliament in proportion to their population. On 25 October, a mass rally was arranged at Chittagong seeking the implementation of the eight-point demand. He said they would “boycott the vote, if necessary” and would not accept “mockery in the name of democracy”.

As of this writing, tensions had escalated in Bangladesh as Chinmoy Krishna Das was arrested and accused of sedition. In a violent clash between police and the followers of Chinmoy Krishna Das left a lawyer, 32-year-old Saiful Islam, dead in Chittagong, leaving at least 10 injured. In response, six involved in the violence were arrested. However, protests erupted in demand for the banning of ISKCON (International Society for Krishna Consciousness), even though Chinmoy was expelled and had no relation with the organisation, as clarified by ISKCON. Political parties urged citizens to practice patience during the turbulent times as the BNP Secretary General Mirza Fakhrul Islam warns people of “evil efforts to divide the nation”. The arrest of Chinmay caused a stir in India, protests were staged condemning the talk of banning ISCKON. The High Court, however, dismissed the plea for the ban, commenting: “The harmony among people here [in Bangladesh] will never be broken.”

In such quickly changing currents, the worsening strain in India-BD ties paired with Wahsington’s possible shift in policy regarding Dhaka can hamper the transition to democracy and prospects of reformations – the key aims of the July uprising.

For the youths in Bangladesh, the challenge lies in identifying the truth from propaganda and fighting with empathy. Aryan Biswas*, a 22-year-old student from Dhaka, rejects the “label of a minority”, embodying a growing wave of young Bangladeshis who are determined to fight for an inclusive and united nation. As the interim government strives for a smoother nation-building process, protecting the vision of a discrimination-free Bangladesh rests on its people. Protecting one another is essential to tackling communal tensions, to upholding the sacrifices made in July – including the untimely deaths of children like Riya Gope. Many “minorities”, (an alienating term) like Asha joined the Anti-discrimination Movement in hopes of breaking free of the cycle of communal tensions. She remains optimistic still, remarking, “Bangladeshi Hindus love this country very much, they want to live without fear.”

*The names of the individuals were altered to protect privacy.