By Gemini Wahhaj

As mass protests unfolded in Bangladesh in July and August of this year, op-eds on the political situation in Bangladesh flooded US media. Noticeably absent from the coverage was any Bangladeshi opinion. Bangladeshis based in the US hastened to pitch articles to various outlets about the violence of the government against student protesters. Nadeem Zaman was one of them. He says, “I’ve either heard nothing back from pitches or been told they’re not suited to their needs.”

A surprising number of US outlets relied on Indian journalists and Indian experts to cover the political situation in Bangladesh, in apparent ignorance of the role of the Indian government in maintaining the ousted Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s regime and the current political conflict between India and Bangladesh. These include opeds by Sadanand Dhume in Wall Street Journal and Brahma Chellaney in The Hill). India has considerable stakes in Bangladesh, yet these Indian journalists do not disclose their vested interest in Bangladesh and the continuation of Sheikh Hasina’s government, and Western media seems clueless about the conflict of interest of Indian writers close to the Indian state analyzing Bangladesh.

There was some good reporting by Indian journalists. During the protests, on July 23, at a time when it was dangerous for Bangladeshis to speak out, Salil Tripathi, author of The Colonel who would not Repent: The Bangladesh War and its Unquiet Legacy and frequent contributor to Foreign Policy and The Caravan, appeared on Democracy Now and explained why students were protesting, the mass dissatisfaction with the government, growing economic inequality in Bangladesh and the employment crisis, worsened by government nepotism enacted through a quota system that gave jobs to government party loyalists. He articulated a politics of hope, saying, “And maybe from these highly patriotic and spirited student demonstrators, we’ll see a new form of leadership emerge.” The New Yorker’s Isaac Chotiner interviewed Indian scholar Subho Basu, author of Intimation of Revolution: Global Sixties and the Making of Bangladesh. Basu explained the conditions that led to the breaking point of Sheikh Hasina’s rule, including repeated rigged elections in 2024, 2018, and 2014.

But there was also disinformation from Indian commentators. In an opinion published in The Hill, Brahma Chellaney claimed that the ouster of former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina was a result of “a quiet military coup in Bangladesh”. Chellaney did not provide any evidence for a military coup. Nevertheless, he insinuated that the student protests were a “media narrative.”. He also characterized the protests as “violent student-led, Islamist-backed protests”, again, without providing any evidence. These articles use racist language for fear mongering, raising the specter of an Islamist uprising in Bangladesh, and the myth that Sheikh Hasina and her party Awami League were the last bastion of moderation in a country overrun by Islamic militants. In his opinion piece, “Bangladesh’s Shaky Political Future”, Dhume argues that “For all her flaws, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina may be preferable to the alternatives—including hardened Islamists eager to gain power.” In his interview with Democracy Now, Salil Tripathi says that there is no basis for the claim that Islamists will be back in power, either through the Jamaat-e-Islami party or their partners the Bangladesh Nationalist Party, headed by Khaleda Zia:

“So, to imagine that she is somehow manipulating or choreographing an entire protest movement against Hasina is, well, a nice theory, but — I think it’s a nice narrative, but it’s very hard to establish that is the really the BNP which is at the forefront of it, or, for that matter, the Islamic party, Jamaat-e-Islami, which has never won more than 12% of the vote in Bangladesh, in 1991, and in the elections since, never more than 6 or 7%. So it is not a very popular, large force.”

The US media seems unaware of Indian writers’ vested interests in respect to Bangladesh. A Wikipedia search on Chellaney reveals that he served in the Indian government’s police advisory group under the external affairs ministry in the 2000s. Sadanand Dhume has long been an advocate for the far-right, ati-Muslim BJP government of India, advocating for their mainstream political participation, praising the high popularity of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the economic performance of the government, and defending the more nefarious actions of the government. In 2023, he pushed back by criticizing the Canadian government when it raised objections to the killing of an Indian Hardeep Singh Nijjar on Canadian soil in 2023.

It is highly problematic for US papers to use Indian bureau chiefs and Indian analysts to comment on Bangladesh, given the multiple conflicts between the two countries. There is a dispute about water sharing between India and Bangladesh. Bangladesh is a riverine country highly dependent on agriculture and fishing. Multiple dams built by India on transboundary rivers divert water away from Bangladesh, causing salinity and decreased flow. While the former prime minister Sheikh Hasina’s government was in power, India built several dams, drving up rivers during the lean seasons and worsening flooding during heavy rains. Sheikh Hasina also signed an agreement with the Adani Group (Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s close associate) to buy power at an exorbitant cost of one billion dollars to Bangladesh, in a sweet deal for India. Indian authorities along the Bangladesh-India border called the Border Security Forces (BSF), tasked with policing smuggling, border crossings, and other illegal activities, have long been documented shooting at Bangladeshis along the border and committing violence on border communities. In the past few days, two teenagers were killed by Indian forces at the border, Mohadeb Kumar, and Swarna Das. In the case of Swarna Das, Indian authorities removed the body and tried to claim that Das had been killed within Bangladesh, blaming her death on a disinformation campaign by Indian media and politicians about a Hindu genocide occurring in Bangladesh, which has been repeatedly debunked by BBC, Al Jazeera, and DW News. The Diplomat reports “Documentation by another rights organization, Odhikar, reveals that at least 1,236 Bangladeshis were killed and 1,145 injured in shootings by the Indian border force between 2000 and 2020.”

In addition, Sheikh Hasina has long been suspected of calling the Indian army to enter Bangladesh during the bloody BDR (Bangladesh Rifles, which had been reconstituted as BGB, Border Guard Bangladesh) revolt and massacre of army officers in Pilkhana in 2009, a crime which was never properly investigated. An excerpt from the book ‘India’s Near East: A New History’, by the Indian author Avinash Paliwal in Scroll states “If the order came, Indian troops would enter Bangladesh from all three sides. The aim was to secure the Zia International Airport (renamed Hazrat Shahjalal International Airport) and the Tejgaon airport. Subsequently, the paratroopers would wrest control of Ganabhaban, the prime minister’s residence, and evacuate Hasina to safety. The Brigade commander overseeing the operation began distributing “first line” ammunition meant for use during active combat. A “very unusual” act, it underscored the severity of the moment. The Bangladeshi army’s reaction was a concern. If Bangladeshi generals turned against Hasina, they would resist Indian soldiers.” After the 2009 BDR massacre, Sheikh Hasina engineered massive changes in the armed forces and installed her loyal men everywhere. The wide public sentiment in Bangladesh is that in exchange for security for her regime, Sheikh Hasina sold Bangladesh to India and essentially became a puppet state, to the extent of being ready to call Indian troops against its own armed forces.

The former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina government projected an image of rapid economic growth. In reality, that rapid growth did not get transferred to the masses, as most of the money was probably funneled out of the country through massive corruption. In reality, for fifteen years, the former Prime Minister led a regime of terror and enforced disappearances, financial corruption, judicial corruption, and repression of speech. The government passed a Digital Security Act, which was used for mass surveillance. There have been successive waves of protests and government crackdown, including the brutal crackdown on young protesters in 2018. The Nobel Laureate Professor Mohammad Yunus, Chief Advisor to the caretaker government, wrote recently, “Unfortunately, we have also become known for having our democracy erode into autocracy, with sham elections in 2014, 2018 and most notoriously 2024 overshadowing the vibrant ones held in 1991, 1996 and 2008. No Bangladeshi younger than 30 has ever cast a vote in an unrigged national election.”

During the protests, the Bangladeshi political theorist Badruddin Umar gave an interview to the Bangla-language paper Bonikbarta, which was later translated in English, in which he said, “We are currently witnessing a significant and widespread mass uprising against Sheikh Hasina in Bangladesh. To understand the true nature, causes, and potential consequences of this uprising, one must look at the historical uprisings in this region. Without this context, the current uprising cannot be fully comprehended. Notably, Bangladesh is the only region in the Indian subcontinent where such mass uprisings have occurred several times. The first was in 1952, the second in 1969, the third in January 1971, and the fourth against H M Ershad in the 1990s. Each of these uprisings led to a change in government.The current mass uprising has created a situation where it will be difficult for the government to survive.” A few days later, he was proved correct. A difficult path lies ahead for the interim government to bring the country back to stability. All institutions have been destroyed. There is no money in foreign reserves. Inflation is high, with high food prices. Nobody can predict what the future holds for Bangladesh, but the measure of a revolution does not lie in its sustainability. This region has seen repeated revolutions against oppressive rulers, predating the independence of Bangladesh, whenever the prices of food and essential goods have risen, when people have gone hungry, and when people could no longer stand the rulers’ violence. At these times, no amount of violence could bring the situation under control. We just witnessed another revolution.

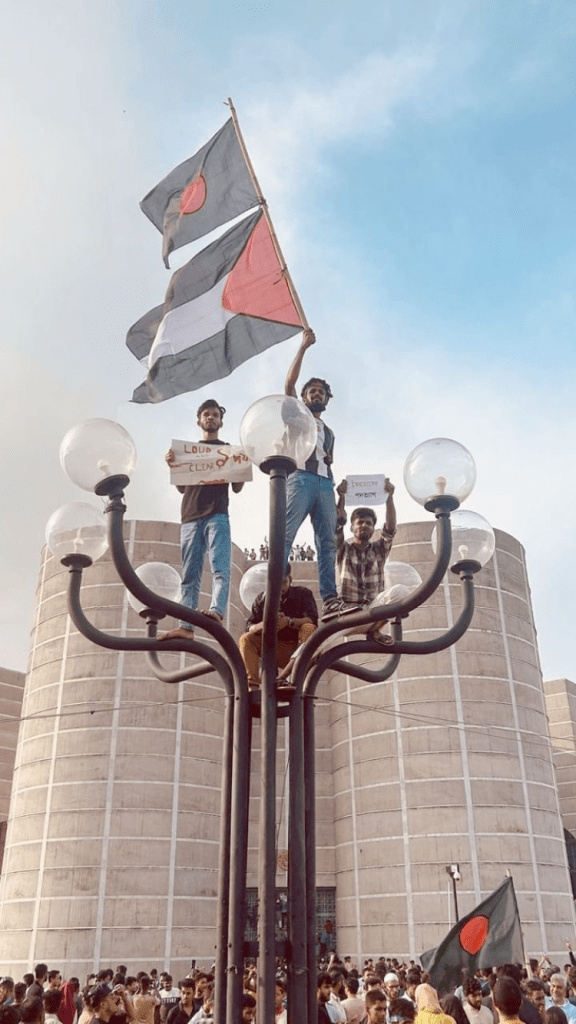

Local reporting by eyewitnesses and journalists in July and August showed that the students from public and private universities protested across the country, and later included high school students, teachers, lawyers, doctors, nurses, garment workers, and rickshaw pullers. In a recent interview, The Daily Star reporter Zyma Islam described journalists’ effort to get out the truth. “We knew that showing the scope and the methods of the violence was key to holding the government accountable.” A blog post by Naveeda Khan, John Hopkins University professor of Anthropology and author of Muslim Becoming: Aspiration and Skepticism in Pakistan, on July 27 showed how the protest movement began and how they escalated in an expected way because of repression and an inability on the part of the government to listen. In another blog post on August 4, Naveeda Khan documented how protesters used slogans, protest on walls, revolutionary songs, posters, and caricatures to mock the government that held them powerless.

An August 14 post by Naveeda Khan compiled the kinds of jokes and mockery used in messaging by the student movement. In an article written during the Internet blackout, Associate Professor of Political Science at Colgate University and author of India’s Bangladesh Problem: The Marginalization of Bengali Muslims in Neoliberal Times, Navine Murshid wrote, “After all, this was a movement borne out of unemployment and bleak job prospects for students. The PM’s rhetoric simultaneously trivialized and politicized their concerns by calling them rajakar — both of which explain the explosion of anger in the following days.” In dispatches smuggled out of the country during the protests and government blackout, writer and photographer Shahidul Alam documented the violence against students and the mounting determination of students to seek accountability for their peers who had been killed, injured, and detained. Journalists like Shafiqul Alam risked their lives to report on the mass uprising, running to sites of violence and morgues to gather information in an atmosphere or terror and information blackout, and provided important context of the government’s corrupt activities.

Although many papers have sought out Bangladeshi voices recently, including Jacobin, NPR, and The Economist, it remains a big problem that US media have no Bangladeshis on staff to report on Bangladesh. Asking Indian analysts to comment on Bangladesh is akin to having Putin opine on Ukraine.