By Tasmiah Rahman

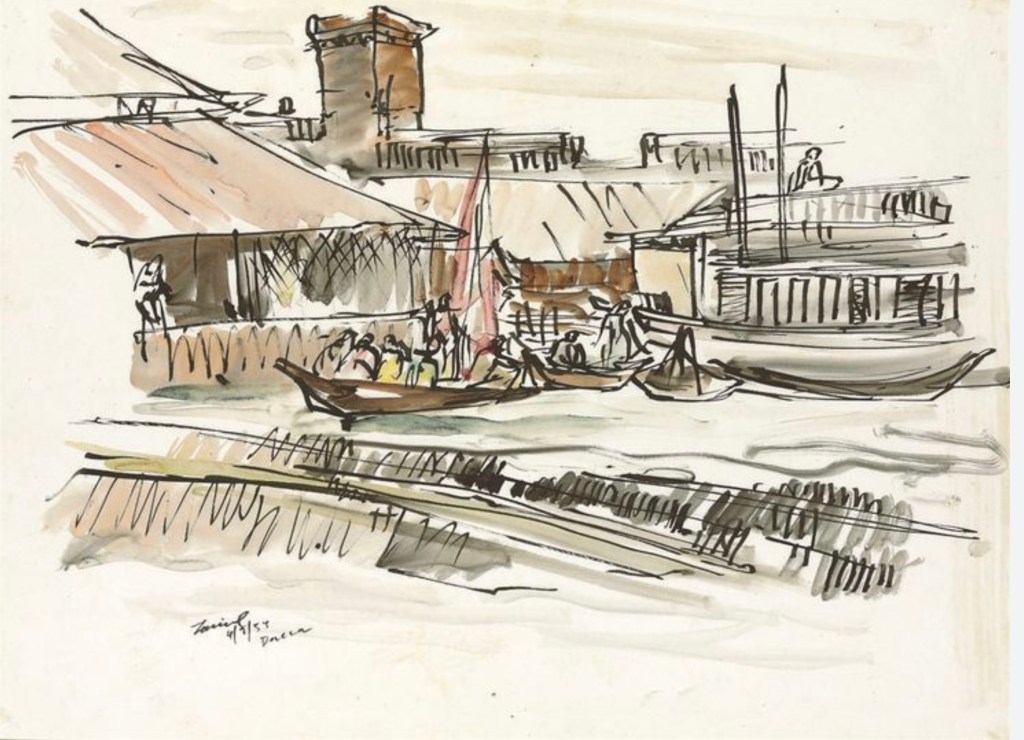

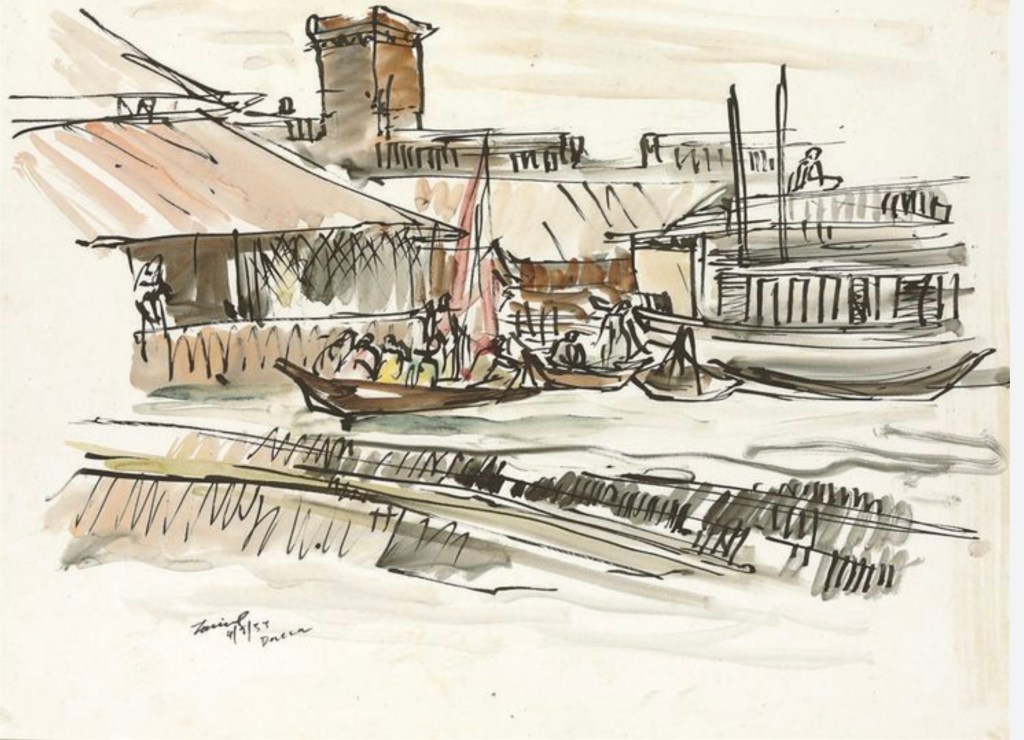

A Team of Bangladeshi Architects Attempt to Tackle the Shelter Problem at Disaster-prone Localities of Delta

Scenes of seasonal mustard, paddy, jute fields, Bithi or tall-green parades [1] of banyan, mango and coconut trees stretch out on two sides of serpentine riverscapes compose the visual mosaic of quintessential Bengal. Here, vigorous watercourses form settlements with Basat baari or humble homesteads, nouka or boats sail around ghat to ghat (river) for trade and communication, ghatpaar (riverbank hubs) and bot-tola (sheds of Banyan trees) exude blissful expressions of life, hosting bazaars (markets), melas (fairs) or jatra-pala (folk drama). The interplay of earth and aqua, and how human life oscillates around it has been a muse for Bengali’s mystical introspections, literary creations, and political reflections for generations.

Historically this warm, and humid country was called the Land by River Ganges or “Gangaridai”. [2] Today Gangaridai is called “The Bengal Delta” the world’s largest and most populated delta, encompassing 100,000 square kilometers of Bangladesh and West Bengal, making home to over 156 million people.[1] The incessant flow of deltaic waterscapes shower blessings of fresh drinking water, agrarian land, protein-rich fish, and surplus products for trading. Contrarily, it can show an unfaithful contempt for the human lives of this river land by causing a catastrophe, drawing a dire picture of the Sonar Bangla (Golden Bengal). [3]

The spasmodic events of flash floods, tidal waves, tropical cyclones, droughts, and landslides topple the national economy, questioning the long-term plans to tackle the perils on the road to prosperity. The result of these tragedies is bleak as they turn the ordinary humdrum of lives into cries of homelessness, paralysis of poverty, and deprivation of healthcare, education, sanitation, and basic needs. As of August 2023, floods and landslides have disrupted 1.3 million lives in the southern parts of Bangladesh including the densely populated Rohingya camps in Cox’s Bazar. [4] Relocation of those affected and emergency response continue in these places but the issue of sustainable solutions to the ecological and humanitarian challenges regarding the settlement crisis demands to be addressed.

Uthaan (Courtyards), surrounded by ghar or rooms made of bamboo, thatch, and clay- form a typical house unit of Bengal. These house units weave together as a cluster and fashion settlements, usually near a river. [1] During torrential rain and wind, they become exposed to the pitfalls of rough weather, causing a periodic shelter crisis at the disaster-prone localities. The tidal Bengal Delta and the rapidly changing weather conditions require wise design thinking in the practice of architecture where the “waterness” of the sites of Bangladesh will be acknowledged. [5] Many architects, urbanists, and architectural critics are drawing attention to wet narratives, as Professor Kazi Khaleed Ashraf claims, “the future is fluid.” [6]

F.A.C.E – Foundation for Architecture and Community Equity led by Bangladeshi architect Marina Tabassum of Dhaka attempts to execute the concept of amphibious architecture to practical implementation by targeting climate refugees, ultra-low-income, vulnerable populations, while receiving international appreciation for the distinct approach. As the chief architect of Marina Tabassum’s Architecture (MTA), Tabassum’s design philosophy strives to create a modern architectural language, keeping the context of climate, place, culture, and history in mind. Her Aga Khan award-winning Bait Ur Rouf Mosque is remarkable for its rare mosque iconography that functions as a prayer hall and a community gathering space simultaneously, catering to the needs of the densely populated locality of Dhaka’s outskirts. Her exploration of flood and cyclone-resilient shelter was inspired by the close study of the river and its banks. A land where water plays the most vital role, instead of resisting and fighting it, Tabassum says, “we should use it to our advantage and learn to live with it” [7]

In search of answers, Marina Tabassum and her team F.A.C.E started the investigation and drew on the design of Khudi Bari tiny House made of bamboo, steel joints, and tall grass. Just as one can assemble and unassemble the parts of furniture from Ikea, Khudi Bari enables the house owner to move and relocate without losing his resources. As research continues, Marina Tabassum emphasizes a multidisciplinary approach to tackling the crisis. [7]

The Bengal Delta – Tales of A River Land

The geometry of 700 crisscrossing rivers smears the idea of a solid shape of wet and dry as the span of some of the rivers is oceanic, where one bank is invisible from the other. This irregular spatial backdrop has caused a philosophical quandary in the psyche of the users of this space. Fakir Lalon Shah- a mystic folk singer who looks at the river and yearns for salvation-

“Aami Opar Hoye Boshe Acchi,

Ohe Doyamoy-

Paare Niye Jao Amay.”, meaning:

“Helplessly I await

Oh Merciful

Take me to the shore”

Prominent novelist Manik Bandopaddhay tells a tale of a low-income minor community of fishermen in his novel “Padma-Nodir Majhi” (Boatman of Padma) where river Padma is the center of livelihood, transportation, traditions, and habits. The ebb and flow of Padma bestows her boons and snatches them away as well.

The paradox of Padma portrays humans as mere puppets of her whims. It is one of the greatest forces of rhythm and wrath in the Delta, born as the Ganges – a Himalayan river. The Bengal Delta, consisting of the Ganges and the Brahmaputra, passes to the Bay of Bengal as a united river. [3] These two rivers merge with a non-Himalayan river, called the Mighty Meghna, having created the Brahmaputra- Ganges-Meghna Delta, or the Bengal Delta. Meghna contains powerful tides as the main supply system of freshwater that begins at the Himalayan mountain ranges downstream with a fierce course towards the Meghna River estuaries.

Meghna carries 1 trillion cubic meters of water and 1 billion tons of sediments yearly. [3] The land and freshwater are distributed to rivers and rivulets (beels, and jheels). [3] The vital river channel systems set up the Great Bengal Delta, having created a rather complex drainage system. [3] The delta is a flat terrain, a few centimeters matter in differentiating wet from dryness. This is the very essence of the majestic moistness of the soil of Bengal and its robust fertility. Bengalis are a deep-rooted “water-based” civilization. [8] The “rice culture” is an inseparable part of Bengali identity. They boast the legacy of “Maache-Bhate Bangali” owing to the availability of cash crops and fish. [8]

River, Rain, and Wraths

The six seasons of Bengal synchronize with the agronomic cycle of Bengal, rejoicing the rituals mostly relating to reaping and harvesting of crops, and the festivity of each season features diverse hallmarks. Seasons include Nabonnao, Poush Sankranti, Chaitra Sankranti, Pahela Falgun, to name a few. The first Bengali month Baishakh exalts the tradition of “halkhata”. On Pohela Baishkh, shopkeepers, merchants, and traders close old ledger books and start anew in longings of well-being. Boishakhi Mela displays clay dolls matching agricultural scenes, harvests, and fishing that are commonly featured in folklore, most popularly the Royal Bengal tiger.

Barsha or monsoon splashes with rain showers, The autumn, or Sharod occurs with fields of white-hot Kans Grass and ceremonies of Durga-Puja. In the nostalgia of winter, Poet Jibanananda Das wrote—

“Abar Ashibo Phire—

Dhanshiritir Teer ey, Ei Banglay—

Hoyto Bhorer Kaak Hoye, Kartiker Nobanner Deshe—

Kuashar Buke Bheshe Ekdin Ashbo Kanthaler Chayay”

Thoughtful customs and prayers of prosperity prove to be short as the ruthless weather situation coupled with looming weather changes damage the distinct nature of specific seasons. Grismokaal or the summer season in April and May causes sweltering heat, at times exceeding 40 degrees Celsius with horrid humidity. [9] “Allah Megh De, Pani De, Chaya De re Tui” is a famous hymn, a plea to God for clouds, water, and shade from the savage summertime. When Kaalboishakhi or the northwestern storm strikes- with its thunder raid and hailstorms, hundreds of houses in countryside settlements suffer substantial damage. [9]

Rains and rivers are the rhyme and rhythm of Bengal, posing insolvable riddles in the alluvial land geometry. No other season captures this innate Bengali parallel as the monsoon does. The beauty of monsoon is best captured by Rabindranath Tagore who writes numerous utopian verses, such as:

You have gifted me the first blossom of kadam of this monsoon.

I am here to offer you the songs of Shravana.

On each Shravana, with the flood streams of your ambiguity

My songs would fetch loads of admiration for you.

The torment of the stern heat declines with the onset of comparatively cooler breezes that bustle after May. Asharr and Shravana generate jovial drizzles as July sees the heaviest downpour. [9] Varying from year to year, extremely heavy rainy days from July to September can cause overflowing on the shores of the deltaic streams, resulting in a fluvial flood. [10] The low-lying landscape and the critical location of Bangladesh being north of the Bay of Bengal add more grounds to a severe cataclysm.[11] According to a 2019 report, 139.6 million people in Bangladesh are at risk of frequent flooding due to the Himalayan river systems. [10] From too little water in the summer to a superabundance of it – water becomes an endless source of vexation for Bengalis. Rabindranath Tagore, an eternal romanticist of rains could not help being skeptical about the torrents, as he wrote:

“The flood, at last, has come upon

Your dry riverbed.

Cry for the boatman,

Cut the cordage,

Launch the boat.

Set the sails,

Let happen what may.”

The stoic presence of the Bay of Bengal compels the seaside region of Bangladeshis to be distressed and vigilant, frantically watching out for the next storm. Extra fragile to storm surge flooding due to repeated tropical cyclones with high tides, Autumn, preferably known as post-monsoon, sustains the highest historical death toll in the coastal areas. Most of the severe cyclones make landfall from October to November. [10] From 1990 to 2021, 90 significant flood incidents were documented due to tropical typhoons. [10]

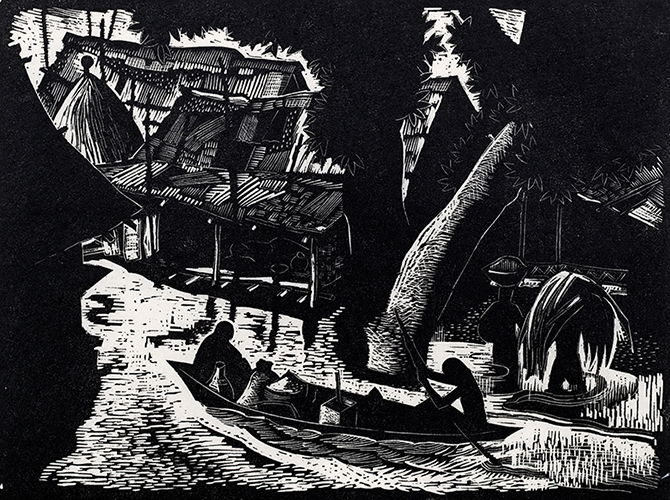

An overflow of wind and water in the matrix of floodplains results in a merciless washout of the usual lifestyle. Irresistible waterness surely evokes a sense of longing and belonging within the soul of Bangalis. Yet Poet Jasimuddin’s portraiture of Asmani, a malaria-stricken penniless young girl living in extreme poverty, whose frail house is at the brink of collapse — makes a ghastly case of this obscure wetland. The realistic recital of Asmani’s life echoes helplessness and calls for action and awareness. Perhaps it is favorable for a significant class of people to turn a blind eye to the prosperity of the marginal, ultra-poor district but for the sake of protecting the future generation, we should pay attention. Because incompetence regarding climate consciousness soon will torment every class and race, including the privileged collective who might immaturely presume they would remain untouched by the perils.

Curses in the Coast-From Bhola to Amphan

When the air becomes boiling-hot and saltwater reeks of it, reaching the highest saturation point when the wind can no longer blow – the world stands still in the dampness. Clouds wrestle in the sky, turning jet black. Soon the warm air turns ice cold and thunders roll quickly, the whirling dance of cyclone begins.

Years ago before modern technology took over, remote villagers had to predict the storms by looking at the signs like the nature of winds and clouds to watch out for the storms. Prominent writer Shahidullah Kaiser’s notable novel Shareng Bou, tells the story of a similar village by the coastline where heavy rainfall caused by tropical cyclone disrupts the relocation of the populace, and soon tidal waves devour the entire settlement. The author renders the sheer dread in the eyes of victims who look death in the eye, defenseless and petrified. The storms are retribution from God and there is no way to escape His wrath – they believe in their final moments, asking for God’s redemption repeatedly.

The 575-kilometer-long coastline of Bangladesh is an ideal target for such vicious wrath, with nearly five tropical cyclones striking each year, shattering lives and livelihoods into pieces. [12] The mayhem of cyclones in the seaside areas of Bangladesh broke all prior records on 12 November 1970, when a deadly depression in the Bay of Bengal developed into a cyclone, later named as Bhola Cyclone. The 6-meter tidal surge and average wind speed of more than 225.3 km/hr resulted in 300,000 to 500,000 people being killed, making this the worst tropical cyclone of all time and one of the deadliest natural catastrophes in modern history. [12] The aftermath of the Bhola cyclone left the people of then-East Pakistan outraged enough to cause a stir in the political circumstances but the damage of $490 million (USD 2009) was done. Meteorologists were aware of the storm, but lack of means of communication caused massive deaths, a lot of the victims died during sleep, blissfully unaware of the turmoil.

In recent years, Cyclon Sidr, Aila, Fani, Amphan, Sitrang, Mocha, and Hamoon have reminded us over and over how unprotected the people of the nearshore zones are. In recent years, casualties have dropped and the construction of cyclone shelters has risen. But the question of a complete cure for the disease still dangles. Once again humans are proved powerless before the immense force of water.

Refugees of Chars– A Cycle of Loss and New Beginnings

The mystical appearance and disappearance of river islands within a vast waterscape is a virtual manifestation of the transcendence of the Bengal Delta. The flow of sedimentation in the alluvial plain causes river channel movement, the creation of mid-channel sand bars, and Charland (riverbed). [13] Riverbank slumping and erosion cause land, settlement, and agricultural losses each year, these marred lands re-emerge to form tiny islands locally known as Chars, which give new prospects for resettlement and livelihood rebuilding. [13]

A Charland has no specific outline, as it arises as a metaphysical mainland and departs too, only offering temporary shelter to the rootless. Thus it can be said that Bangladesh’s map does not have a concrete shape, it is constantly changing.

When the landform is constantly shifting, building a house on it gets complex, if not impossible. The common codes of construction and space design do not apply here. Almost 20 million people arrive to live here, people who belong to the most minor, indigent, and deprived communities. They do not have permanent shelter, proper healthcare, education, or a sanitary system. [14]

When the rain hails more excessively than average and rivers surge, the habitats of river islands start counting days in preparation to move to a safer locality. If they continue to stay inside for safety and health conditions, they might get waterlogged for weeks, being deprived of pure drinking water, sanitation, and food. They move and lose their belongings and means of livelihood and are bound to start over again. Just as the mighty rivers change their flow according to their course, these river islands keep shaping and reshaping the lives of these people.

Nongovernmental organizations (NGO) and Char (river-island) Livelihood Programs take up flashy projects like river bank protections, cross-dams, and so on. Being oblivious to the fact that the morphology of river islands is not compatible with these technical constructions, rather it demands floating or elevated structures. As these business ventures, a recent study shows nearly 9.4 million people were displaced internally in 58 districts in the last 7 years due to extreme weather events. [15] Efforts have reduced the death rate but can these climate refugees recover the loss in their lifetime? What is the future of these children? Did they want such an uncertain life?

The Next Storm

In the remote areas of Bangladesh, the increase in salinity in water is causing reproductive health problems in women. The rise in temperature during summer and erratic rainfall throughout the year has declined agricultural production and it is projected to drop by 17% which contributes half of the income per capita in Bangladesh. About 42% of the people live below poverty, and 85% live in rural areas. The GDP of Bangladesh already suffers by 1-2% due to climate problems which is projected to increase.[16] Malaria, dengue, chikungunya, diarrhea, and cholera are causing epidemics multiple times a year.

Bangladesh is learning to tackle the recurring natural disasters. In 1976-2001, droughts affected 25 million people, floods affected 270 million people, and rain and wind storms affected 41 million people. [17] Improvements have been made, and lessons are being learned at a great cost. Due to the rise in carbon emission followed by global warming, the snowcapes have started melting, making climate change the next big storm for Bangladeshis to watch out for.

Climate change is expected to cause grave effects in Bangladesh by 2050, making 13.3 million people migrants, according to World Bank. The esteemed features of climate change include increases in the extent and recurrence of floods and tropical cyclones, sea-level rise in the Bay of Bengal, a decline in fresh surface water availability, and an increase in soil salinity along the coast, many of which have started already. Because of the reduction in agricultural income, many of the farmers have adopted extra labor, like day labor, rickshaw/van pulling, etc. Recent studies have postulated that climate change will lead to more poverty. Lack of basic needs such as food, shelter, education, and healthcare- will force them to leave their farmsteads and arrive in the urban localities, especially in Dhaka.

“Pristine river of lives

is swallowed by the crowd–

Human getting lost into humans.”

– Suman Pokhrel

Right now, a large part of Dhaka city stands on water. To produce more land, natural water resources in Dhaka’s periphery are being concealed and filled with soil, brick, and cement. Pretentious real estate projects base their businesses on volatile water-based land. While climate migrants elope to the city, in fantasy to make a fortune, Dhaka functions unsafely. Habitants of the mega-city aspire to immigrate to a different city outside the country to avoid pollution, traffic, and price hikes. The question now draws itself, how long do we run from water? More importantly, how effective it is to run from water?

A Tiny House in a Vast Waterscape

When Marina Tabassum and team F.A.C.E planned Khudi Bari they considered the important factors of the delta plain and the realities of climate refugees. This Tiny House aspires to connect and withstand the waterscape. To hold out the floods, Khudi Bari’s idea of long bamboo legs draws inspiration from old traditions of vernacular architecture that works as an elevated plinth. People used to make their houses on a comparatively upper ground level so that flood water could not enter their rooms.

The first Bari was installed in Char Hijla, Chandpur. The main material of this house is bamboo which is available in almost all areas of Bangladesh and is inexpensive. The Facade of the house is built by using tall grass which comes in handy. The house has a pitched roof system, using corrugated metal sheets- a common material used to build houses in rural Bangladesh for decades. This tiny two-storied house has bamboo legs to hold iron on the ground using clay and steel joints. The upper floor is used as a bedroom during the time of flooding. The total cost of Khudi Bari is 300 Euros, which is financially efficient given its flat-pack use and flood-resilient performance.

Right now, team F.A.C.E is working on 100 prototypes as the research project is funded by the Swiss Government. It is now trying to test how Khudi Bari can adapt to the community. It is important to remember that Khudi Bari is an architectural intervention into the vernacular architecture system that has been in tradition for many years. For Khudi Bari to function efficiently, “without the roaring noise of architecture”, the users’ acceptance is mandatory.

To install the Khudi Bari in a community, Team F.A.C.E prepares a brochure that explains the project in an easy language, with diagrams. Then the local people are invited to make a map of their area, they get to choose which place would be suitable to test the prototype and they take part in the construction.“When people make something with their hands, they engage and make it their own,” says Marina Tabassum. The research is receiving worldwide acceptance as Marina Tabassum was nominated third-greatest thinker of the COVID-19 era in 2020 by Prospect, a UK-based magazine. [18] Her philosophy is to make the water work to our advantage. “Instead of trying to fight the water,” Marina Tabassum says, “we should embrace it”.

“When you plunge your hand into the water, all you feel is a caress”.

– Margaret Atwood

Water flows, as inevitably, as truthfully as fire burns, and air floats.

Water does not resist. If we place a wall on it or establish streets and sleek skyscrapers over it, water would penetrate and keep streaming – by leaking, flooding, or storming in. Water is nature, it finds a way. It is to stay unceasing, never to be seized within human fists, to be fully fathomed, nor to be battled against. The God-like unruliness of ours to govern nature only confirms our diabolical egomania. So far, it has deluded us into dreary conjunctures of today’s climatic and ecological doom. We must retrospect, that our eldest ancestors in Bengal had witnessed and withstood the mysticism and musicals of rivers, and we will too. The clouds will forever burst, water will pour down, and eternal rains will come. As paradoxical, dilemmatic, or detrimental as it may sound.

The waterness in the land of Bengal we see is hereditary, in terms of culture, geography, and ideology. The wisdom of water has been passed down to us. We must go with the flow as water does. It is our existential anthem, a prelude to the deltaic spatial milieu. In a land of increasingly blurred lines between earth and aqua, solid and liquid, indoor and outdoor, oceans and shores, spaces are to be designed concerning the Bengal-core elements. Our architecture and urbanism must create a dialogue with the delta and its humans, and humans must adapt to realize that true resilience rests with living with water.